World Antibiotic Awareness Week takes place November 13-19 this year to raise awareness of resistance and encourage best practice across sectors.

Despite fears over resistance first emerging decades ago, the topic has, more recently, risen up many agendas, and become recognized as a major threat to health, prosperity and even security. There are estimates that US$40 billion is being sought over the next 10 years to tackle the problem.

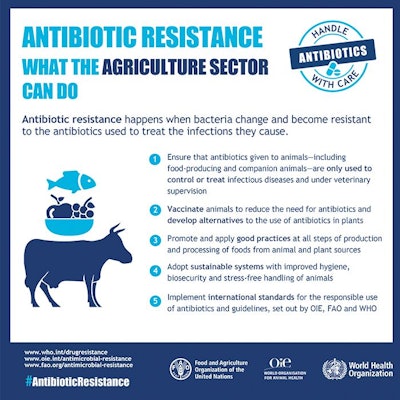

2017 is the third year that World Antibiotic Awareness Week is taking place, focusing on human health care, agriculture and the environment, and is part of the WHO global action plan, "Antibiotics: handle with care."

Through a variety of initiatives across sectors, the week aims to improve awareness and understanding of antimicrobial resistance, strengthen surveillance and research, reduce infection incidence, optimize medicine use and ensure sustainable investment in counteracting resistance.

Commenting during last year’s Antibiotic Awareness Week on the use of antimicrobials in veterinary medicine, FAO Chief Veterinary Officer Juan Lubroth said: “It also occurs in our food system because of the overuse, misuse or abuse of antimicrobials in order to either get additional profit, produce more food, the use of medicated feed, because good production practices or hygiene is not followed, so the risks are great under unsanitary conditions. So farmers or veterinarians or whoever will use antibiotics, and that is inappropriate.”

Grassroots education is key

While drug-resistant infections kill approximately 700,000 people a year, by 2050 this could rise to 10 million – more than the projected 8.2 million deaths from cancer – and tightening regulations on antibiotics will not be enough to solve the resistance problem.

No matter how strict rules may be, if not monitored or properly implemented, they will have little effect. What is essential is education to ensure that prescribers and users better understand how antibiotics should be used. Change is needed at grassroots level, and, in some cases, this may mean greater access to and use of antibiotics.

A recent publication by the Antimicrobial Research Centre in London points to studies conducted in parts of India that look at health workers who treat humans and animals.

These health workers, with no formal training, can sell antibiotics, with the length of treatment depending on whether an animal or person is the patient. Treatment can be extended if more antibiotics are available and affordable.

Risk, however, does not only come from poor controls or misunderstanding of use. In developing countries, people tend to live in closer proximity to animals, raising the likelihood of the transfer of bacteria, and farm workers may have less protection.

The report also points to countries where the sick may not have the funds to visit a qualified doctor and so go to the “drug shop” -- convenience-type stores without pharmacists or doctors, that sell antibiotics without prescription.

The problem of antibiotic resistance is neither simply a developing world nor a developed world issue, but a global problem. However, how it is addressed needs to be adapted to suit local circumstances.

For example, health care systems in some developing countries may not be equipped to deal with patients carrying drug-resistant infections. Such patients would simply be turned away from further treatment and not represent a cost. In developed economies, however, the issue has been presented to policymakers and hospitals as a major economic burden.

Where poultry production is concerned, in addition to legislation, more meat is marketed as being antibiotic free, or producers are only able to receive quality marks if they follow standards regarding antibiotic use. However, different regions of the world are moving at very different speeds and, as in human medicine, attitudes vary enormously.

In June, statistics were published showing that the poultry industry in one country had cut the volume of antibiotics it used in broiler production by more than 70 percent over five years. Shortly afterwards, poultry producers in another country were accused of breeding “super bugs” through heavy use, and poor controls.

A study in this latter country found that “antimicrobial use for growth promotion promoted the development of highly resistant bacteria on the studied farms with potentially serious implications for human health.”

One of the report’s authors noted that easy access to antibiotics, inappropriate prescribing practice and a lack of awareness were all major issues on the farms studied.

You’ll also learn about: