The broiler and turkey industries in the USA have experienced dramatically different supply and demand situations for commodity meats over the last few years, but they are both feeling the same pinch from high fuel and feed costs. Live production managers and veterinarians at integrated broiler and turkey companies and extension personnel who specialize in live production were surveyed by WATT PoultryUSA to find out what trends are emerging in a number of areas. Topics discussed include downtime and placements, new housing, house cleanouts, flock health, animal welfare and on-farm salmonella control.

In response to poor economic conditions many poultry integrators reduced chick placements starting last fall. Integrators were asked how these reductions were accomplished in the field.

One major integrator said that the way in which the cutbacks were applied varied from complex to complex within the company. Reduced placement densities, increased downtime between flocks, and a reduction in the number of growers on contract were the means used, in varying degrees, by the company in reducing the total number of chicks placed.

Other integrators surveyed reported that decreases in the number of chicks placed were accomplished by extending downtime between flocks.

Joseph B. Hess, associate professor and extension specialist, Auburn University, said that prior to the industry's recent decrease in placements, some complexes were operating with downtimes of three to five days between flocks. "This led to obvious disease in some cases and to an erosion of performance in others. Recent slowdowns in placement, if they lengthen downtimes to 10-14 days, will improve the health of flocks in our region," he said. Increased downtime can lead to improved health and performance and this can mean more pounds per flock, but it will mean fewer flocks placed per year.

A veterinarian for an integrator explained that the relationship between downtime and subsequent flock health is not as straightforward as might be anticipated. "Long downtime is not a cure all. Short downtime can get you in trouble with infectious disease, but extended downtime won't necessarily get you out of trouble once you have it," he said.

Flock Health Impacted By Downtime

Integrators responding to the survey report that in general flock health is good, but some infectious diseases continue to be nagging problems in individual complexes or on certain farms. One veterinarian reported that despite placement cuts which have given his company extended downtime between flocks, an increase in disease is being experienced. Specifically, "runting and stunting" and laryngotracheitis (LT) are on the rise. Another veterinarian reports that his company has seen more runting and stunting this winter, particularly in a small-bird complex. He said, "Cleaning out houses that have had runting and stunting has had some impact, but it isn't a cure."

Necrotic enteritis and dermatitis were both mentioned as being sporadic in occurrence by survey respondents. Several veterinarians noted that necrotic enteritis has not been a problem for their flocks which are raised as "antibiotic-free" and vaccinated for coccidiosis.

One veterinarian said that immune suppression seems to be playing a role in the diseases that are vexing the industry, such as "runting and stunting," clostridial diseases and respiratory infections. Finding the root cause of the immuno-suppression could be the key to reducing the impact of these diseases and syndromes.

The turkey industry suffered through a year with relatively low flock livability in 2006. Heat loss, early poult mortality, loss of use of some antibiotics and dermatitis were identified as the causes of this increase mortality in the "Poultry Industry Executive Survey," which appeared in the January 2006 WATT PoultryUSA.

Several turkey integrators have adopted brood-and-move strategies for tom and heavy-hen operations and have even begun raising light hens on single-age, partial-house brood operations. One veterinarian explained that brood-and-move was not implemented in the operation for disease control purposes. Instead, the system was adopted to increase the annual pounds per square foot through brooder houses.

For heavy toms or heavy hens, the brooder house can be used to raise two flocks in the time that a finisher house raises one flock. So a brood-and-move strategy can generate the same pounds per square foot as a three-age, two-stage farm. This veterinarian said that his company has seen improvement in brooding with the brood-and-move approach, because under the old two-age, two-stage system the grower, and/or the hired help, only brooded 2.5 times per year and some growers seemed to forget how to properly ventilate the brooder house from flock to flock.

On a traditional two-age, two-stage farm, birds are moved from the finisher house as soon as possible to get them out of the "relatively crowded" brooder house. With the brood-and-move approach, at least two integrators have seen benefit from building in downtime between flocks in the finisher houses. One integrator has seen reduced incidence and severity of gut E. coli disease and respiratory E. coli problems. One live production manager in the turkey industry thinks that downtime between flocks is particularly important now that the industry has lost the use of some medications.

Dermatitis is a disease that used to be extremely rare in the turkey industry, but it has become a real problem for some operations. The infection responds well to medication, but it is still a costly disease when it occurs. One live production manager speculated that there may be a correlation between dermatitis and improper composting of mortalities. "Dermatitis may be a problem because growers track it in from the composter," he said.

Energy-Saving Steps Being Taken

Energy costs can account for up to half of a grower's total operating costs, reports James Donald, P.E., professor, biosystems engineering and poultry science, Auburn University. "Retrofitting steps are being undertaken to help reduce propane and electricity usage. Examples are sealing and tightening, solid sidewalls, addition of insulation and the addition of stir fans. We also see much interest in buying highly energy efficient ventilation fans and replacing older heating appliances with more efficient radiant units," he said.

Broiler and turkey industry respondents report that there are a small number of growers who are using alternative means of heating their poultry houses. The most commonly cited alternative fuel was wood, but other growers are burning corn, coal, litter and used motor oil. Some of these growers are relative newcomers to the use of alternative fuels, but others have been heating their houses in this manner for years.

Use of energy-saving sodium vapor and fluorescent lighting is widespread in the turkey industry since the lights in turkey houses do not need to be dimmed. Broiler lighting programs require energy-saving lights that can be dimmed, such as cold cathode bulbs. Jess Campbell, poultry housing field coordinator, biosystems engineering, Auburn University, said, "There is a major trend to install the higher efficiency lights that we have seen on the market. They have the potential for reduction of the lighting portion of the electric bill."

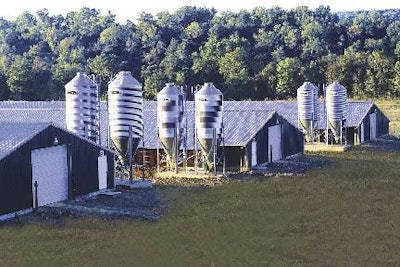

Despite Cutbacks, New Housing Being Built

Despite chick placement cutbacks, broiler integrators are still signing new growers and these growers are building new houses. The reason for this is attrition. Integrators must replace houses that are taken out of service by weather, fires, grower retirement or because the houses are outdated and cannot be retrofitted economically. Every broiler integrator responding to this survey reports that new houses are now being built in most complexes.

One integrator reported that his company needs to replace 5 percent to 7 percent of its housing each year just to make up for attrition. This number might seem high until you think back to some of the building booms that the industry experienced 20 to 30 years ago. Just as the retirement of the "baby boomer" generation will cause a shock wave in the work force, the aging and obsolescing of houses built during major building programs of the past may require significant building efforts today to replace them.

Several turkey complexes are engaging in major building programs to support increased slaughter volume. Farbest Foods in Huntingbird, Ind., added a partial second-shift early in 2007 and expanded its growing operations to support this. Bil Mar (Sara Lee) is expanding its growing operations in Iowa to replace birds lost to Dakota Provisions. Some members of Dakota Turkey Growers Cooperative are building more houses to fill their quotas at Dakota Provisions. Industry sources report that Prestage Farms in South Carolina is contracting with additional growers who are building houses to supply an increase in slaughter at the Louis Rich (Kraft Foods) plant in Newberry, S.C. slated for 2008.

None of the turkey integrators who replied to this survey are requiring that new houses be tunnel ventilated, but several offer a house design where tunnel ventilation is an option. According to survey respondents, most new turkey houses being built are curtain-sided and are not tunnel ventilated. Some of the new tom houses are being built for use in brood-and-move programs, but many are being built as two-age, two-stage farms.

Because of high material costs and the advances in equipment, integrators are having trouble getting new broiler and turkey houses to cash flow. Most broiler integrators are specifying a wider house because they cash flow a little better.

Gene Simpson, Ph.D., professor, agricultural economics and poultry science, Auburn University, said "There is certainly a trend to larger and wider houses. Larger houses have a better chance of cash flowing due to the economies of size and scale."

One broiler integrator reports that, given current interest rates and a 10-year loan, a new house only nets around $4,000 per year to the grower for the first 10 years. Some broiler and turkey integrators are paying a bonus per square foot for new housing. Broiler integrators report that most new growers want to build as many new houses as they can borrow money for. The typical new grower builds four houses. One broiler company veterinarian said, "I think that overall a four-house farm is better than a two-house farm, because it is more of a full-time job and keeps the grower around."

Increasing regulation of poultry growing can make building new houses more expensive as well. Dan Cunningham, Ph.D., University of Georgia, said, "Environmental and nuisance issues are making it more challenging to get new poultry house construction done in many areas. In Georgia, a new NPDES permit requiring soil erosion control plans for construction of poultry houses is adding thousands of dollars to the cost of building. New house construction is continuing for some companies, but, in some areas, zoning regulations and setback restrictions are making it more difficult to site new house construction."

Animal Welfare: This Is Only The Beginning

Broiler and turkey integrators responding to this survey report that they follow animal welfare guidelines established either by their respective trade association or by customers. These companies also report that they perform both third-party and internal audits of compliance to these programs. Poultry companies have taken good first steps in audits, but researchers and extension personnel say that the poultry industry still needs to do more to communicate with consumers.

Francine A. Bradley, Ph.D., extension poultry specialist, University of California-Davis, said, "The broiler industry, its members and trade associations, need to act now. Animal terrorists and activists are currently targeting the layer industry. They have already waged campaigns against foie gras producers and game fowl breeders. The broiler industry needs to tell its story first. They should not wait to be the next sitting ducks."

This sentiment was echoed by Frank T. Jones, Ph.D., associate director, Center of Excellence for Poultry Science, University of Arkansas. "The traditional strategy that many commercial poultry companies have used to communicate with consumers might be thought to resemble some traditional southern football teams that were much stronger on defense than on offense. This approach gave satisfactory results as long as most of the population had some sort of understanding of production agriculture. At present, however, a very small percentage of the U.S. population is involved in food production and few know or care about the specifics of production. Indeed, this apathy makes U.S. consumers vulnerable to many messages, both positive and negative, which could affect consumption patterns. The poultry industry needs to go on offense' (maybe West Coast Offense!') with respect to telling its story to consumers," Jones said.

Keeping consumers educated and informed will continue to be important for the poultry industry, because now that welfare programs have been established and accepted by the industry, the activist groups will apply pressure to tighten standards.

Bruce Webster, Ph.D., professor and extension poultry specialist, poultry science, University of Georgia, said, "No one should think that current animal welfare audit programs are sufficient. They will be reviewed on a regular basis and changes will be made as new knowledge, opportunities, or demands dictate. Retailers will not always make science-based decisions regarding animal welfare requirements, but will on occasion pursue initiatives based on what they perceive to be the realities of the marketplace. Retail marketers of poultry products are on the front line of the animal welfare debate and will face unremitting pressure to surrender to the demands of animal advocacy groups. Some will make concessions, placing pressure on other retail companies to follow suit. The worst thing poultry companies can do is try to dig in their heels and resist progress. It is important for industry leaders to recognize that animal welfare is a moral issue and that the public expects the poultry industry to embrace and promote the moral consensus that exists in society in regard to the welfare of agricultural animals."

On-Farm Salmonella Control Presents Complicated Picture

Several broiler and turkey companies report taking intervention steps on the farm to try and reduce salmonella numbers at the processing plant. Some report that they are acidifying the drinking water for the last three days that the birds are on the farm. Also, some companies report using autogenous vaccines in breeder flocks to reduce salmonella numbers, with somewhat mixed results.

One broiler company veterinarian said, "We vaccinate for four serotypes of salmonella, yet all we culture out of the chiller is one of the serotypes we vaccinate for. So is the vaccine working? Maybe for the three we don't culture, but evidently not for the one we do." Another broiler company veterinarian said that his company's vaccination program seemed to be helping reduce salmonella, but "this has to be an active program, you need to keep monitoring and updating your vaccine," he said.

One broiler company veterinarian said, "There is a breed relationship with salmonella, some broiler breeds have more salmonella than others." This veterinarian believes that how resistant a breed is to salmonella colonization may play a part in which breed the integrator chooses for its operations in the future, just as breast meat yield and feed conversion do today.

Finally, one broiler company veterinarian said, "It should be remembered that USDA is evaluating an incidence rate (positive/negative) rather than a number of salmonella microbes. Indeed, our work has shown that when doing most probable numbers, the actual number of salmonella is quite low out of the chiller. Ninety-three percent are "less than 2," meaning none was detected. On the few samples from the scalder, the number is also quite low, usually less than 10. As a result, we find it difficult to attribute much impact to measures taken in live production on our salmonella levels as they are currently being measured."