Sanderson Farms, the third largest poultry producer in the U.S., is committed to taking a fresh approach to everything it does, and not only where its poultry products are concerned but company wide. That approach earned the Laurel, Miss.-based company the prestigious Clean Water Award at its lone further processing plant located in Flowood, Miss.

Sanderson, which operates 10 poultry processing plants in Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina and Texas, took over the operation of the stand-alone further processing plant in Flowood (located just east of Jackson across the Pearl River) in the mid-1980s.

Handling 80,000 pounds of processed poultry meat each day, producing products such as portioned breaded and battered nuggets and tenders and marinated chicken wings, the Flowood plant generates 75,000 gallons of high strength process wastewater (under one gallon per pound of meat processed) daily. That wastewater is pretreated on-site prior to discharge into the city of Flowood municipal sewer system.

2012 Clean Water Award

Sanderson Farms is known for its corporate-wide – and often unique – operational approaches and standards, and the Flowood facility’s environmental wastewater pretreatment system is no exception. This was a key element in earning the facility the U.S. Poultry & Egg Association’s 2012 Clean Water Award in the pretreatment category.

When the Clean Water Awards judges initially reviewed the two years of process wastewater effluent data submitted for the Flowood facility, they were left scratching their heads trying to figure out how the discharge monthly averages for chemical oxygen demand, total suspended solids, and oil and grease could be only a small fraction of permit limits. They came away from the site visit impressed not only with the facility’s wastewater treatment performance but also by the facility’s design and construction, daily operation, system monitoring, and even to the relationship of the plant’s environmental staff with the local regulatory authority.

Pretreatment plant performance

Wastewater treatment plant performance is measured by the quality of the effluent discharged, and in the case of the Flowood facility, the numbers speak for themselves. As shown in Table 1, the plant’s maximum use of pretreatment permit parameter limits is only 10 percent of the allowed oil and grease concentration (7 of the 67 mg/L permit limit). For both chemical oxygen demand and total suspended solids, the plant uses only 4 percent of the daily loading limit (38 lb/day chemical oxygen demand and 39 lb/day total suspended solids of the 917 lb/day permit limit for each parameter).

“That’s the way we do everything in the plant,” said Sanderson Division Manager Paul Billingsley. “We don’t look at what’s minimally acceptable. If someone gives us a specification on a product, the minimum specification is not our target. If someone give us a permit limit, that maximum limit in not our target. That’s the way we treat everything, including wastewater.”

Pretreatment system design

When Sanderson Farms acquired the Flowood facility in 1986, process wastewater treatment was achieved through a series of grease traps, which required multiple pump outs each week. The city of Flowood, along with the rest of the Jackson metropolitan area, saw significant growth throughout the 1990s that resulted in increased pressure on the municipal wastewater treatment system. By 2000, Sanderson Farms realized that to remain sustainable at the Flowood facility it would need to invest in a pretreatment system designed to provide significant treatment of the process wastewater generated at the plant prior to discharge into the city sewer system.

In fall 2002, Sanderson Farms Flowood began operation of a new 0.175 MGD process wastewater pretreatment system designed by Environmental Technical Sales, Baton Rouge, La., with equipment manufactured by Environmental Treatment Systems, Acworth, Ga.

“The system was designed to handle more than our projected maximum hydraulic load for years to come,” says Kevin Miller, the person assigned to ensure environmental compliance at all Sanderson facilities. “The system has been in operation for almost 10 years now with no major problems with the equipment.”

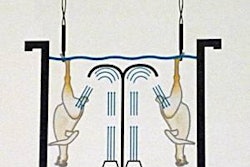

All of the process wastewater generated by the plant flows into a 40,000-gallon lift station that provides equalization prior to pumping the wastewater into the first of two dissolved air flotation, DAF, units.

“The goal of the first DAF unit is to remove as much insoluble organic material as possible,” Miller says.

Effluent from the first DAF then flows to a 300,000-gallon aeration tank fitted with a 75-horsepower floating aerator that provides biological treatment. Flow then continues through a second DAF unit before exiting the system.

“The biological treatment we get in the aeration basin allows us to capture soluble organic material, which normally can’t be removed in DAF systems,” adds Miller.

The skimmings removed from the surface of the partial recycle DAF units are sent to two dedicated holding tanks that allow for decanting (separation of the solids and free water) prior to pick-up by Terra Renewal, a private land application company.

Pretreatment system operation

Flowood’s Environmental Quality Supervisor Shannon Franklin oversees the operation of the pretreatment system on a daily basis. “The key for us is that the system allows for the operation of DAF1 in a batch mode,” Franklin says. “Once the lift station fills and equalizes, we run jar tests on that batch to tune in the amount of polymers we use. The amount of each polymer we use changes because our product mix varies so much in the plant, each batch of wastewater can be very different.”

“Shannon keeps a schedule of all the product runs we plan on throughout the workweek,” says Billingsley. “We produce 85 different products at this facility, and it’s not uncommon for us to make two to three product changes in a day.”

“DAF systems typically work more efficiently if they are operated in a continuous mode,” says USPOULTRY’s Vice President of Environmental Programs Paul Bredwell, “but the Flowood’s wastewater profile is constantly changing, and the staff here applies DAF technology in a unique way that ensures maximum treatment.”

Pretreatment system monitoring

While many industrial wastewater pretreatment facilities focus almost entirely on their final effluent analytical values, Sanderson Farms Flowood uses daily analytical testing at multiple locations in the pretreatment system to monitor treatment efficiencies in each unit operation.

“We run [chemical oxygen demand] and [total suspended solids] on every batch generated in the influent lift station,” says Franklin, “so we know what's coming into the plant. We then run [chemical oxygen demand] and [total suspended solids] on the effluent from DAF1, the aeration basin and DAF2 prior to final discharge. That way we know how each step in our treatment process is performing.”

“We do the same thing at Flowood as we do at all of our plants,” Miller says. “We use analytical tests at each stage of the process so that we know what treatment level we are achieving throughout the process, not just the end result.”

Pretreatment system regulation

USPOULTRY’s Clean Water Award judges were impressed with the open and positive relationship the Flowood staff maintains with the local environmental regulatory pretreatment program. In Mississippi, the state department of environmental quality issues all industrial pretreatment permits, while in many municipalities, local pretreatment program coordinators monitor industries within their system boundaries to ensure state permit compliance.

“We set up our sampler to collect effluent samples every week,” Franklin says. “The city pretreatment inspector makes quarterly inspections, and during those times, he sets up his sampler next to mine. We then work together to split each of the composite samples we produce and then share our results to make sure everything matches up.”

Perhaps Billingsley sums up the approach of Sanderson Farms best. “Anyone can be average,” he says, “we don’t ever want to be average.”

The Flowood wastewater pretreatment facility is anything but average.