Many pig producers try to fine-tune sow nutrition, particularly during the gestation period. High raw material prices and increased feed costs are spotlighting sow gestation nutrition to improve cost-efficiencies, while maintaining or improving productivity in pig breeding herds.

Sow feeding can be divided in three phases: lactation, weaning to insemination interval and gestation. Feeding regimes are targeted to meeting the needs of the sow during these three phases.

1. Sow lactation

During sow lactation, it is necessary to ensure good intakes of high-quality feeds are maintained. The sow must do her best to meet the requirements of the piglets as well as maintain body condition to support good reproductive performance her subsequent cycle. It is often very difficult to reduce feed costs in this period and any compromises in diet are not advisable.

Because the amount of lactation feed compared with the total feed amount varies 30 percent to 50 percent, depending on the country, it is always good to review high amino acid (AA) profiles and the additives in use to make sure they fit the current sow production levels. Feed must meet the requirements of the lactating sow, based on the number of piglets suckling as well as their growth. Sows with smaller litters of less than 11 piglets may not need high feed levels.

2. Weaning to insemination

Weaning to insemination is quite short so there is not much to gain with regards to feeding costs. Sows should be flushed in this period as this has been shown to increase litter size and in some cases litter uniformity. If a lactation feed is being used, it should be replaced with a gestation feed once the sow is inseminated to avoid unnecessary feed costs. The higher protein level in a lactation feed also can have a negative effect on the sow.

3. Gestation

Gestation is longer and this is where a review of a sow feeding regime may lead to some improvements that could improve a pig herd’s economic performance. It used to be typical to gradually increase sow feed during gestation. For gilts this is a common practice, because they do not need to recover from lactation and they are still growing to reach mature size.

For gestating sows, more knowledge of her nutrient requirements has led to a different recommended feeding pattern. It is now more typical for pig producers to follow a ‘high-low-high’ sow feeding schedule. This is based on the idea that in the first part of the gestation, the weaned sows need to recover from lactation losses.

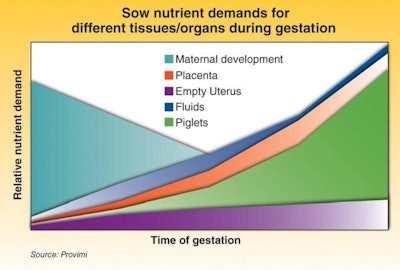

Sow energy demands

This might be for the first 30 or 50 days depending on the recommendation of the genetics company. Energy demands for embryos and fetuses are still low at this time. During mid-gestation, sows need to be fed to maintenance plus extra to meet the nutritional demands of the developing fetus. Secondary muscle fibers are formed in this period and their growth will be compromised if the nutrient supply is too low.

Feed research has also shown that a lack of nutrients in this phase can negatively affect the embryo later in life, affecting the performance of finishing pigs. In addition, research by Markham et al., 2009 has shown that meat quality can be compromised, if the sow’s nutrient supply is too low in this mid gestation phase.

If the energy intake during mid-gestation is too high, sows will become too fat which can negatively influences farrowing and subsequent lactation performance. During the last part of the gestation, above day 90, fetal growth increases dramatically and needs to be supported with increased nutrients. At this stage of gestation, sow feeding levels will be at their highest.

Sow body condition

It is common practice to condition score sows to determine the necessary feeding level during early gestation. Different feeding curves will be used for thin, normal and fat sows. On many pig farms, sow body condition is assessed visually. However, several studies have shown that this visual assessment does not correspond well with back fat measurements.

For example, a Belgian study by Maes et al. (2004) showed that only 45 percent to 50 percent of the classifications based on sow body condition scores agreed with classifications based on back fat measurements. For first parity sows only 32 percent of the observations corresponded.

Back fat measurements are mandatory when feeding curves are based on sow body condition. Having an insight in the true body condition of sows—using back fat measurements—will help increase the effectiveness of using different feeding curves and can reduce the variation in sow body condition within a pig herd. An even better predictor of sow body condition is weight loss. This has been shown to be more closely related to sow reproductive performance than back fat losses (Hoving, 2012). Weighing sows is very informative and can be used to help optimize feeding strategies.

Recent studies show that a weight loss of 10 percent to 13 percent seems to be acceptable for primiparous sows, without negatively affecting reproductive performance (Schenkel et al., 2010; Hoving et al., 2012). However, sow nutrient intake during early gestation should then be high enough to support body reserve recovery.

Sow parity

Another factor that should be taken into account is sow parity. Ideally two different gestation diets should be formulated, one for younger and one for older sows. Sows in their first and second parity have a higher nutrient demand, especially for amino acids, compared with older parity sows because they are still growing.

Younger sow diets should aim for an optimal development of muscles. A higher proportion of amino acids for more back fat with a higher ratio of digestible lysine to energy compared to diets of older sows. While younger sows need more amino acids, older sows have a relatively lower need for amino acids.

Older sows do need more energy for maintenance and to replenish body reserves after lactation. Because it is often not feasible to feed two different gestation diets to sows of varying age, a compromise is typically made and younger sows get a higher energy diet than they need, while the supply of amino acids does not meet their needs. Older sows typically end up with lower energy than required, but with higher amino acids.

This means that young sows must achieve the right body composition during rearing, because opportunities to complete growth during gestation could be limited. For the older sows, this compromised diet can lead to an increasing body mass but decreasing back fat levels and a decreased easily available energy source during lactation.

Sow gestation diets

Fortunately, techniques such as transponder feeding and batch mixers make it possible to feed two different sow gestation diets—a young and old diet—and even to mix both diets.

For young sows with a high milk production and a high protein mass loss, a mixture of both gestation diets can help improve body weight recovery and longevity. It is worth considering these options in the design of sow gestation buildings and management routines.

When designing sow feeding regimes, the breed should also be considered. The most popular breeds at the moment are selected for lean growth potential of their offspring. They have a higher body mass and less back fat than their counterparts from the past. The high lean-growth potential should be considered when feeding these sows, because they will easily increase their protein mass rather than fat mass.

A higher protein mass increases maintenance demands, which increases feed costs. In addition, heavy sows with a high protein mass are more prone to being culled due to leg problems. Feeding these sows a gestation diet with lower amino acids and a lower amino-acid-to-energy-ratio will help control protein gain, but stimulate back fat gain. The acquired back fat can be used as an easily accessible energy source during lactation and helps prevent sows from getting shoulder lesions.

While sow breed and lactation should be taken into account, it is possible to fine-tune sow diets, particularly in the gestation period. Armed with improved nutritional knowledge and sow data on back fat and weight loss, cost-effective diets can be formulated to meet the sow’s requirements. And by differentiating age of sow and breed, performance also can be improved.