March, 2006- The 1990s saw the building of several new broiler complexes in this country, but the new millennium has been uneventful when it comes to building broiler complexes, until now.

Sanderson Farms began processing birds at its new Moultrie, Ga., plant at the end of August 2005, and it is in the process of ramping up production to the plant’s capacity of 1.25 million head per week. On January 13, 2006, Sanderson announced that it would build another new complex in the Waco, Texas, area, with the opening date for this complex set for May of 2007. WATT PoultryUSA recently visited Sanderson’s South Georgia complex to get a close-up look at the USA’s newest broiler operation.

Bob “Pic” Billingsley, director of development and engineering, Sanderson Farms, Inc., explained why Sanderson is expanding now.

“Our balance sheet guides everything that we do, and as our balance sheet gets to the point where it will support expansion, and that, tied in with what we are supposed to do for our stockholders, determines when we will grow.”

Sanderson is a publicly-traded corporation, and Billingsley explained that the company needs to grow so that it can reinvest its earnings and continue to give shareholders a superior return.

Billingsley has been with Sanderson for 21 years, and part of his role with the company is to develop complexes. The South Georgia complex is the third new complex that Billingsley has helped to build. Sanderson started the process for developing the South Georgia complex in 2004.

The company looked at Alabama, Georgia and South Carolina for potential complex sites. According to Billingsley, Sanderson looked at its established customer base on the East Coast and decided it would be beneficial to expand closer to these customers.

The company goes through a very deliberate process for evaluating potential sites, Billingsley explained.

“We have 50 or 60 independent points that we gather data on, do our homework, and we do very deliberate research on an area until we find an area that we can be successful operating the complex in and the community that we locate in can be successful. After doing our homework, it became obvious that South Georgia was the area that we needed to focus in on, and in particular we looked at the Moultrie area because it matched up best with our criteria,” he said.

One of the selling points for the Moultrie area, which is around 50 miles north of the Florida line, is that no other poultry facilities are in the immediate vicinity. Sanderson held informational meetings for local farmers in March of 2004 to gauge interest in contract broiler production.

One site selection criteria for Sanderson is the demographics of the farmers, and Billingsley said, “That is a plus of this area.”

Local farmers raise peanuts, cotton, bell peppers, tomatoes and cabbage on row crop farms, and there are also pine timber plantations. Billingsley said that local farmers will be able to land apply the broiler litter, following Georgia nutrient management guidelines, without a problem.

One of the challenges in locating a plant in South Georgia is that processors are not offered the opportunity of having a direct discharge permit for processing plant wastewater. Land application systems (LAS) are necessary. Sanderson had to find 1,000 acres in close proximity to the plant to house the LAS.

Billingsley found the land needed for the LAS around six miles from the Moultrie site selected for the processing plant. Next, the company had to find land on a main rail line to site a feed mill. The feed mill and hatchery were built in Adel, which is 25 miles east of Moultrie off of I-75.

$70 million plant

The Moultrie plant started processing on August 22, 2005, and it will be up to its capacity of 1.25 million head per week by late May of this year. Broilers are processed at seven weeks of age at an average weight of 5.8 pounds per bird. There are two 140-bird-per-minute kill lines, and each feeds two 70-bird-per-minute evisceration lines. The company did not choose high-speed (140-bird-per-minute) evisceration lines because managers there believe that the trade-off of quality and yield is not worth the increased speed.

Industry sources report that high-speed evisceration equipment, which pulls the viscera pack out of the carcass and holds it away from the bird, also removes some of the leaf fat, and this reduces yield. Using more, low-speed lines means that Sanderson employs more labor, floor space and capital to eviscerate the same number of birds as could be handled on high-speed lines.

Equipment from Stork, Meyn and Johnson is used in first processing at the Moultrie plant. Two Stork MX cut-up systems are employed after the chiller. Billingsley said, “The MX line lets you manage your yield and lets you get the product where it needs to be without adding labor to the process. It reduces redundancy; you only hang the bird once.” All the birds are hung on the two MX cut-up lines and birds are cut-up, deboned or used as whole birds depending on weight and grade.

Each part on each bird can be cut-up or deboned depending on weight and grade and the requirements entered onto the computer. For instance, a breast can be split or dropped off for aging and deboning depending on size and skin coverage. A leg saddle can be cut into leg quarters, whole legs, or drum and thigh depending on weight and grade. “The MX lets you sort by value of yield,” Billingsley said. This is the first MX system that Sanderson has on the retail side of its business. “It has been a good decision for us for product quality and yield,” he said.

Moultrie is a retail traypack plant, and it has 18 Ossid 500E over-wrap machines which, according to Billingsley, provide the “latest and greatest” in a moisture resistant and leak proof package. Moultrie also employs two model 2700 Cryovac vertical leg quarter bagging systems and two model 2600 Cryovac whole-bird bagging machines. After, trays are over-wrapped, they are put into crates, which go on dollies and then go through a drag blast for 50 minutes. Upon exit from the drag blast, the trays are pre-priced on Ossid high-speed pre-price equipment, and are boxed and shipped.

When the plant is operating at capacity, it will employ around 1,400 people. Billingsley reports that the complex had 3,400 applicants for the first 300 jobs. Sanderson has had no problem getting people for any of its locations, he said, and the new complex has not been an exception. The company typically brings in top managers and a few key people from other Sanderson locations to a new complex but hires locally for all other positions. Training of key personnel is done at other Sanderson locations prior to start up of a new facility, and typically only a few people are brought in from outside.

Opening the Moultrie plant has allowed Sanderson the opportunity to shift the product mix at its Collins, Miss., plant. In January of this year, the Collins plant had a one-week shutdown to allow for new equipment to be installed. Collins had run big birds and traypack sized birds on two lines, but the plant will only run big birds for deboning in the future.

In a December 2005 press release, Joe F. Sanderson, Jr., chairman and chief executive officer of Sanderson Farms, Inc., said, “With the conversion of the Collins, Mississippi, plant to a larger weight bird and the additional retail capacity from the Georgia facility, we will increase our overall production by just over 26 percent when both projects are running at full capacity and will also continue to maintain a favorable product mix between the retail market and the big bird deboning market.”

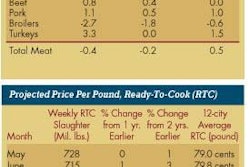

Sanderson Farms ranked sixth in the January 2006 Top Broiler Company survey with 30.39 million ready-to-cook pounds processed per week in 2005. The additional volume in Moultrie and Collins in 2006, and the new complex planned for Waco in 2007, could move Sanderson further up the broiler company ranking in the next few years.

'No surprises'

Billingsley said, “There have been no surprises; we are very deliberate in what we do. We have an extensive due diligence process that we go through, so we have not had any surprises.” He explained that there was some exceptionally wet weather in South Georgia during the time the complex was being built. The rain delayed construction of broiler houses a little bit and slightly delayed the ramp-up in slaughter at the plant initially.

“You couldn’t ask for a better reception then the one received from local farmers and the community. We have not waited on growers at all. We have done a lot of educating about what we expect from growers and what they can expect from us,” Billingsley said.

This education process means that most folks who say ‘this is not for me’ understand this before they build a house. Billingsley noted that this process helps to assure the success of the prospective growers and Sanderson Farms.

Sanderson did not offer any special incentives to attract growers; the company just offered its standard contract. “We have had some challenges here, but not with securing contract producers,” Billingsley said.

“Historically, that has never been a problem; we have a competitive contract, and we have a 15-year contract for our producers. Our philosophy on that is that if we are going to ask a producer to secure a long-term loan to build a house then we have shown them a long-term commitment by offering a 15-year contract.” The challenges have been with the weather, but new houses are being built, and by Spring of 2006, Billingsley expects the company’s target ramp-up to be met.

Making sure that potential growers understand the responsibilities of being a contract broiler producer before they build the facilities is really important, especially when you consider the size of the grower’s investment. Sanderson is building a broiler house that is tunnel ventilated and, on average, the house costs $195,000 to build, including the cost of site work for a four-house farm. The land in the Moultrie area is flat, so very little grading is required. This complex has a minimum farm size of four houses, though the typical grower is building eight houses.

A total of 500 broiler houses, 48 breeder houses and 24 pullet houses will be built by contract growers to supply the complex, for a total investment by growers of over $100 million. This is Sanderson’s first complex using black plastic panels from Paragon for the interior walls of the broiler houses and black tri-ply on the drop ceilings. The black color for the interior of the house is part of the company’s lighting program.

Sanderson decided to put the feed mill in Adel, Ga., about 25 miles east of Moultrie, because Adel is on the main Norfolk and Southern rail line that runs parallel to I-75. The mill is situated on 100 acres, and a 7,200-foot rail spur has been built on the property so that the mill can handle 75-car trains, the size required to get the lowest freight rates. A 75-car train can be unloaded in less than 16 hours, and the mill has storage for 468,000 bushels of corn. The $11 million feed mill has one pellet mill and will produce 8,000 tons per week in 110 operating hours. Average distance from farms to the feed mill is around 25 miles.

The company also built a 65,000-square-foot hatchery for $11.5 million in Adel. It has 52 Jamesway Super J incubators and at capacity will set 1.5 million eggs per week. The hatchery also has the fully automated Embrex system, and it is air-conditioned and has steam humidification.

Sanderson has a separate management structure for live production and processing at all of its complexes, so there is no complex manager at Moultrie. Live production works out of the hatchery, where a total of 90 hourly and 25 salaried people will be based, including the field service personnel.

Sanderson invested a total $96 million in its new South Georgia complex. When asked, in hindsight, what he would change or have done differently if he could do the complex over again from scratch, Billingsley said, “I wouldn’t do anything differently.”

.jpg?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=crop&h=167&q=70&w=250)

.jpg?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=crop&h=167&q=70&w=250)