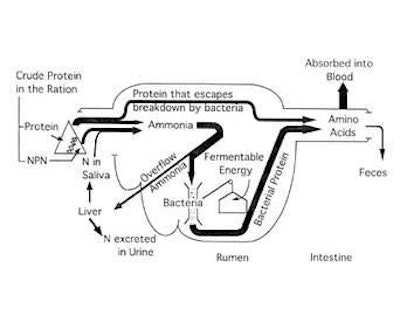

Protein is a critical aspect to any nutritionist, but in order to look at appropriate ways to maximize the supply of protein to dairy cows, we first need to review how protein is metabolized in the rumen.

The cow’s protein supply comes from two sources: dietary protein and rumen microbial protein. Dietary protein may then be further divided into that which is broken down in the rumen (rumen degradable protein, RDP) and that which escapes rumen degradation (rumen undegradable protein, RUP), sometimes called by-pass or escape protein.

Dairy diets are usually comprised of a mixture of both. Non-protein nitrogen (NPN), such as urea, falls into the RDP category and is usually rapidly degraded to ammonia. Rumen microbes use ammonia as their source of nitrogen and use a variety of sources of ammonia to produce microbial protein. They are able to use certain dietary proteins to synthesize microbial protein - enzymes produced by the bugs generate ammonia by breaking down the protein.

The protein in feed ingredients, such as soybean meal and rapeseed meal, is a mixture of both RDP and RUP, providing protein for the rumen microbes, as well as directly to the cow’s small intestine for absorption.

Not all rationing systems are the same

Achieving appropriate quantities of both RDP and RUP is often the basis of protein rationing. Various rationing systems are used across the industry with the aim of achieving a balance of protein sources. Although each system essentially assesses the same basic aspects (protein, energy, etc.) of a diet, they all use different descriptors and don’t necessarily measure the same parameters. Some descriptors are comparable across systems, some are not. All rationing systems are based on prediction equations, but these can differ between individual systems, although they generally all take into account the basic protein parameters – RDP and RUP.

Both the Agricultural and Food Research Council (AFRC, often referred to as the ME, MP system and used in the UK) and the National Research Council (NRC) systems look at metabolizable protein, i.e. that which is available for absorption in the small intestine.

The NRC goes further to evaluate some aspects of degradation in the rumen. The Inra (French PDI) system parameters evaluate the contribution of both feed and microbial protein sources to the protein available to the cow in the small intestine. It takes into account the effect of limiting nitrogen and energy supplies on the amount of microbial protein available. Both the CVB (Dutch) and DLG (German) systems also include parameters for endogenous nitrogen.

Possibly the most intricate rationing system is the Cornell Net Carbohydrate and Protein System (CNCPS). This is a more dynamic model where feeds are described using chemical fractions and fermentation characteristics, giving an indication of how much of any one feed material is degraded in the rumen. This is then used to give an idea of how much microbial protein will be produced. The unique aspect of the CNCPS is that it takes into account the rate at which feeds are utilized in the rumen and thus can detect variation in the efficiency of microbial growth.

Balance is the key

Whatever the system used, the goal is still to achieve a balance of protein sources available to the cow. Traditionally, the focus has often been on undegradable or bypass sources of protein to supply key amino acids to the intestine; but, as microbial protein is deemed the most efficient source of protein for dairy cows, not least because of the similarity of its amino acid profile to that of milk, is it more prudent to consider approaches that maximize its production?

Many years ago, a positive association between dietary protein levels and milk yield was demonstrated in the literature and in practice. This led to increasing protein levels in dairy diets. Nowadays, there is increasing recognition of the over-feeding of crude protein in diets and the negative effect this can have on aspects of production, such as fertility. Increases in blood ammonia and/or urea levels from high-protein diets (particularly those diets that are not well balanced) can adversely affect the condition of the uterus.

Practically speaking, for lactating dairy cow rations the consensus is to aim for ~100g of crude protein supplied for every liter of milk produced. Recent research suggests that a lower dietary crude protein combined with a higher level of non-fibrous carbohydrate (starch) can be effective in improving energy balance in early lactation.

Rumen microbes need fuel

However, it’s not simply about the level of dietary crude protein – as we’ve seen, protein supply to the cow is a combination of both feed and microbial protein. Production of the latter is influenced by both dietary nitrogen and energy supply – supplying the microbes with sufficient nitrogen is one thing, but if they don’t have the energy to turn it into microbial protein, then it is wasted. It would be like having a car but no fuel – the car is ready (the nitrogen is there) but no fuel (energy) means you can’t go anywhere!

Promoting microbial protein is about matching nitrogen supply to energy supply. Assessing feed ingredients for their soluble protein content and viewing this as a proportion of the total RDP will give an indication of the use of that feed ingredient in the rumen.

Matching energy to protein is a qualitative, as well as quantitative process. Rumen microbes use different sources of energy (fiber-digesting vs. starch-digesting) and stimulating these different populations requires a balance of energy sources.

Rationing systems, such as the French PDI and CNCPS system, help give an understanding of how well matched various feed sources are. For example, soybean meal (protein) and cracked corn (energy) have similar fermentation characteristics and are, therefore, well matched. Urea is often used as a source of NPN but it is rapidly hydrolysed to ammonia in the rumen. Practically, this means that, although there is a large amount of nitrogen available for the microbes to use, there also needs to be a suitable amount of energy quickly available in order for the microbes to be able to use it.

Even within the same feed material there can be differences in the protein profile, which can have an effect at the production level. A good example is the difference between solvent and expeller soybean meal. Altering proportions of these ingredients can significantly alter the supply of RDP and RUP, in turn affecting supply to the rumen microbes and to the cow. Additionally, the efficacy with which the degradable portion of these ingredients is used will also be affected by the type of ingredients used as an energy supply. Greater RDP will require more rumen available energy to promote microbial protein production.

In summary, protein is one of the most complex aspects of rationing dairy diets. Microbial protein is the most efficient and cost effective source of protein for the cow, so strategies and ingredients to promote its production should be the first principle when formulating diets.