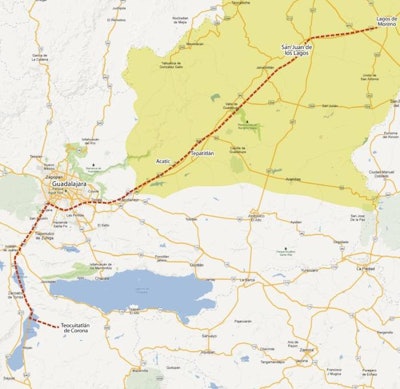

Disease outbreaks in livestock production, such as the current avian influenza outbreak in Mexico, can lead to profound changes in both production and the food chain. This outbreak, which was the subject of the Avian Influenza Symposium at the 38th Aneca Annual Convention this past April, started on Saturday, June 9, 2012, with reports of high mortality in layers in the egg production corridor comprising Acatic, Tepatiltlán and the area of Los Altos in the state of Jalisco, Mexico (Figure 1). Meanwhile, the nearby Atemajac Valley, a large broiler production area, was not infected with the virus.

Importance of Jalisco

Jalisco has 70 million layers in production as well as approximately a third as many replacement pullets prior to the outbreak. These birds were responsible for approximately 55 percent of the country’s table egg production. Mexico has the world’s highest per capita egg consumption, one egg per day. There are also 34 million broilers in Jalisco.

If Jalisco were an independent country, it would be the eighth largest producer of eggs. "For us, it was the worst place the virus could have come; it is the most populated poultry area of the world," said Dr. Arturo Suazo, Sales Manager Avilab Laboratories.

The theory of wild birds

All kind of rumors circulated on the origins of the outbreak. Even the possibility of bioterrorism was investigated, but everyone seems to agree on the role of wild birds. There are bodies of water that provide winter homes for many species of wild birds, which surround several farms. "We believe that this might have been the way this virus disseminated into layer flocks," said Dr. Miguel Angel Marquez, independent consultant for the OIE, FAO and The World Bank. However, the spread could have occurred by contamination of groundwater or by the direct use of untreated water, not only in Los Altos, but in many places.

The outbreak strain of the virus has been isolated from endemic wild birds: the magpie (Quiscalus mexicanus) and the swallow, which are both found in the Los Altos region of Jalisco.

Diagnosis and reporting to the OIE

Dr. Marquez said: "If I had gone to make the first necropsies, I would have diagnosed cholera. Symptoms were of hemorrhagic congestion with petechiae and bruising, and I would have treated with high doses of antibiotics, and if the mortality hadn’t dropped in two or three days, I would have suspected Newcastle.” The diagnostic difficulty resulted in lost days, and finally, the diagnosis was everyone’s worst nightmare: that after 19 years, the low pathogenic strain of H5N2 virus, which had been somewhat silent in many areas, had mutated into a highly pathogenic strain.

On Sunday, June 17, 2012, in an urgent meeting of poultry farmers, authorities and consultants in the Tepatitlán Poultry Farmers Association, it was decided to notify OIE. Senasica, the national food safety agency, officially notified OIE of the presence of an H7 virus on June 24, 2012, which was also when the virus was confirmed to be a highly pathogenic H7N3 strain.

Compared to the 1994 outbreak, "when the virus was practically in half of the country, this time it was restricted to an area of the state of Jalisco,” said Dr. Assad Heneidi, Director, Epidemiology and Risk Analysis of Senasica.

The decision was made to vaccinate poultry with a vaccine derived from a low pathogenic virus that was preserved from an isolate of a migratory pochard, with 98 percent homology to the outbreak virus isolated in 2012. The initial goal was a temporary vaccination, which began on July 26. In the first phase, 80 million birds were vaccinated, and by April 2013, 370 million doses had been applied.

Free from influenza?

On October 24, 2012, the then President of Mexico, Felipe Calderón, announced that the virus was controlled.

But, on January 3, 2013, two unvaccinated layer flocks were found to be infected with the outbreak strain, and, on February 13, 2013, six Bachoco broiler breeder farms were found to be infected. The presence of the virus on breeder farms, which have higher levels of biosecurity, was particularly troubling.

The outbreak didn’t stop here. On April 17, 2013, the virus was found in 950 backyard birds in Tlaxcala. On May 6, 2013, the virus was found in Puebla, the second largest egg producing state in the country.

Effect of the outbreak

Officially, nearly 23 million chickens were either depopulated or died from the virus. The cost of these losses, excluding the value of the lost output, is estimated at $722 million. The egg production lost is estimated at 390,208 million tons of eggs, approximately 15 percent of national production and 26 percent of the production of Jalisco.

The National Poultry Producers Association conducted a study to gauge the effect of the outbreak on egg consumption. Fourteen percent of the population stopped eating eggs as a result of the outbreak, 64 percent say they reduced egg consumption and 21 percent did not alter their consumption. In this survey, 73 percent of the population said they consume eggs because they are nutritious, and only 12 percent say they consume eggs because of the low price.

Biological tsunami

"Every country, whether developed or developing, must have a law, a policy and a compensation fund for livestock producers," says Dr. Marquez. Otherwise, you run the risk of producers hiding the truth of about high mortality or serology, and this can delay response to an outbreak. An avian influenza outbreak should be considered as "a natural disaster, earthquake, flood or biological tsunami," says Dr. Marquez.

According to information from national surveillance, more than 3,000 farms have been sampled, more than 300 million birds are on the surveillance farms, and nearly 400,000 serological, molecular and viral samples have been analyzed during this epidemic.

Risk factors

Several factors have been identified as a result of this outbreak. The avian influenza virus survives in contaminated feces, and vaccination can mask viral circulation (the virus has been isolated in vaccinated, healthy flocks). The outbreak has highlighted biosecurity failures. If biosecurity has failed on breeder farms, would it be adequate on broiler farms? Sales of spent layers off the farm to individuals who slaughter them or keep them as backyard birds can spread the virus. Movement of litter off farms for use as fertilizer on other properties presents a risk for spreading the virus, and, finally, wild birds offer a potential reservoir for the virus.

What is the prognosis?

The prognosis is really worrying. Dr. Márquez notes that the poultry industry in Mexico is at "a historic moment of extreme gravity of unpredictable proportions in domestic poultry." It is essential that there is coordination between the poultry industry, state and federal governments to develop strategies. "Yes, if there is no joint coordination, we will not move forward; the epidemic will continue," said Dr. Heneidi. "We also need to define operationally what technical procedures must apply, what is the immunization of flocks, and not particularly vaccination."

Foundation of the national poultry industry

As stated earlier, the Mexican poultry industry is at a historic moment, a moment for its revival, but how? And that is precisely the problem. The solution will require several steps; deep structural changes need to be taken in the short, medium and long term.

Dr. Marquez has proposed a list of 32 points. One is the geographic de-concentration of poultry in all regions of high concentration in the country; this is a medium to long term, 3-5 years, solution.

Fifty three percent of chicken in Mexico is marketed live, and this is one of the most likely causes of the spread of the virus. On all roads, at least in Central Mexico, chicken trucking companies circulate hauling live birds. Poultry companies of all sizes must have their own processing plants nearby. Ten years ago, when Argentina entered the export market, they built plants, just as in Brazil. They don’t have trucks circulating on the roads with live birds. The goal for 2016 for Mexico should be that there is zero movement of live chickens in the country.

Stopping the movement of cull hens and poultry manure will provide even more difficult challenges. There needs to be a national law on biosecurity, and finally, the establishment of an OIE-certified National Laboratory Diagnosis of Avian Influenza with the participation of producers and the National Poultry Producers Association.