a stepwise process to successfully move away from beak-trimming in all of its cage-free flocks.

Animal rights activists in many European countries have made the practice of beak trimming poultry one of their prime targets.

“There is a big debate about beak trimming in the Netherlands and the U.K. and it has already been banned in Sweden and Norway,” said Dr. Knut Niebuhr, assistant professor, University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna. He told the audience at the International Egg Commission’s conference in Vienna that beak trimming is not forbidden by law in Austria, but it is not allowed for shell eggs sold under one of Austria’s “label marketing programs.”

Seal of approval

Around 80 percent of all farms market their eggs in the two label programs, Tierschutze gepruft and AMA Gutesiegel. AMA stands for Agri Markets Austria, and the label is akin to a “seal of approval” for agricultural products.

Michael Blass, managing director, AMA Gutesiegel, said, “Austrian consumers have quite specific expectations about foodstuffs and they are willing to be quite vocal when it comes to expressing these expectations.”

Blass said the AMS Gutesiegel label represents three things for consumers: The first is premium quality for a commodity; the second is that the food is traceable back to its origin; and the third is the independent sampling, auditing and analysis that is conducted. In a recent survey of Austrian consumers, Blass told IEC delegates, there was a very clear preference expressed for food that is non-GMO in origin, and he said they want eggs from hens that are fed non-GMO feed.

Phasing out beak trimming

In 2000, approximately 43 percent of all flocks in Austria were beak trimmed, and these were all in non-cage systems. Through mediation, which brought together egg producers, retailers, animal welfare groups, veterinarians and scientists, an agreement for a stepwise phaseout of beak trimming was agreed to.

The time frame established was from 2002 to 2005. The agreement set fixed maximum rates of beak-trimmed flocks. There were increasing penalty fees set for farms with beak-trimmed flocks. The fees paid were to be used to compensate farmers with beak-trimmed flocks that show increased mortality due to injurious pecking. The agreement also set up management guidelines and called for scientific monitoring and data collection from the flocks.

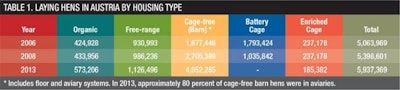

Battery cage housing for layers in Austria was banned in January 2009 and no new enriched cages were allowed to be built from 2005 on, so Niebuhr said that the Austrian experience without beak trimming is essentially a story about management of cage-free flocks without beak trimming. In 2013, nearly 97 percent of all layers in Austria were maintained in cage-free systems (see Table 1). Barn systems housed around two-thirds of Austrian layers in 2013.

Controlling pecking

“If you want to get rid of beak trimming (of laying hens), then you have to try and to control both feather and injurious pecking,” Niebuhr said. “Injurious pecking and feather pecking are probably related, but may occur independently. They are not related to aggressive behavior.”

He said that the development of injurious pecking and feather pecking depends on a combination of different influencing factors, i.e., it has a multi-factorial origin. Genetic predisposition, feeding, rearing and husbandry conditions on the layer farm all can be factors in the development of injurious pecking and feather pecking behaviors in a flock. “Beak trimming can reduce the severity of damage caused by pecking, particularly injurious pecking, but it doesn’t eliminate the underlying causes leading to injurious pecking or feather pecking,” he said.

Stepwise approach

Niebuhr said it is possible to phase out beak trimming with a stepwise approach. He said it is essential to have a framework established between producers, pullet growers, feed mills, veterinarians, scientists and advisers and that the process has to be closely monitored. Expertise is necessary. Doing the conversion incrementally allows for the resources needed to train and advise growers to be available when needed, and this minimizes animal suffering as producers learn how to manage flocks differently.

The percentage of flocks that exhibits injurious pecking in Austria has decreased from approximately 9 percent in 2000-02 when almost all cage-free flocks were beak trimmed to approximately 2 percent from 2010-12 when almost all cage-free flocks were not beak trimmed. The incidence of flocks exhibiting medium to severe damage from feather pecking has also decreased from the 2000-02 timeframe to 2010-12, going from about 30 percent of all flocks down to about 17 percent of flocks.

Phasing out beak trimming makes good management in the pullet and laying houses even more critical, according to Niebuhr. Austria is a brown egg market. He said that feeding a nutrient-dense high-quality ration plays a role in limiting injurious pecking. Niebuhr said you can raise cage-free hens without beak trimming in flocks with low levels of injurious and feather pecking and with relatively low mortality rates, but it isn’t inexpensive.

“You need a good price for your eggs,” he said.