poultry manure has been identified as a major risk factor for the spread of avian influenza in Mexico.

It has been three years since Mexico notified the OIE of an outbreak of highly pathogenic H7N3 avian influenza, and control and eradication efforts are still underway. Today, outbreaks of H5N2 and H5N1 avian flu in the U.S. have brought even more attention. This disease "is no longer exclusive to one area, a county or a state, it is worldwide," says Jose Luis Cruz, director for USAPEEC Mexico office.

Movement of untreated poultry manure, sometimes from one state to another, for use as a soil amendment or for cattle feed has been identified as one of three major risk factors for the spread of avian influenza in Mexico. The other two risk factors are movement of live birds, particularly spent hens, and late notification that flocks are infected.

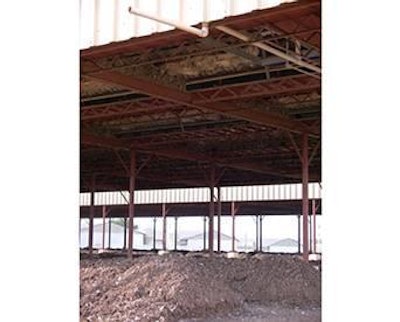

Manure treatment

In Mexico, there are standards that regulate the movement of poultry manure. The Agreement on Reportable Avian Influenza, published in June 2011 in the Mexican Official Gazette, "states that there are two ways to treat manure" says Roberto Señas, director of Poultry Health, Regulations and Quality of the National Poultry Producers Association of Mexico (UNA). One is composting in the poultry house to kill or inactivate pathogens with the heat generating in the composting process. Composted litter can be moved off the farm, but cannot leave the state. In Mexico, Senasica (the agrifood quality agency) validates composting by checking equipment and processes, and analyzing samples to verify that no virus particles are present.

Industrial heat treatment, with a greater guarantee of the elimination of the likely presence of the virus, can be used if the poultry manure is to be moved out of the state where the farm is located. This treatment should be supervised by official staff.

"The Agreement of Reportable Avian Influenza is mandatory throughout the country and for the entire poultry industry," continues Dr. Señas. "Sagarpa (the Mexican Department of Agriculture) does not hesitate to ask manure to be processed, to inactivate the virus, to industrialize manure and to totally ban mobilization of poultry manure out of state," adds Sergio Chávez, UNA's CEO.

Avian flu, what went wrong?

The agreement, however, does not mean 100 percent of farms are checked. "I think what is missing are personnel, infrastructure and probably resources; that is why Sagarpa relies so heavily producers themselves," says UNA's Chavez.

With limited staff and budget, the authorities carry out verifications of facilities with higher risk. "They check with more detail where there are risks, or following complaints or concerns," says Señas. Random checks, to see what farms actually do, are carried out. This represents a drain on resources, but it is the only way to reduce risks.

The government must be responsible and must enforce the law, but the producer must be aware as well that the mobilization of manure and live birds out of the state represent a major risk to other states and to other companies.

In the U.S., "it is also a serious problem," says Jose Luis Cruz, USAPEEC Mexico. "With these current problems, they are reviewing biosecurity protocols to prevent further spread of the virus, such as proper handling of manure." In that country, "companies along with producers will head towards taking many precautions."

How to control manure movement?

When the avian influenza outbreak emerged in June 2012, the situation forced the Mexican government to jump-start the Dinesa: the National Emergency Animal Health Mechanism. In it, the army, federal police and local police coordinate with Senasica to help prevent unregulated and high-risk mobilizations out of state, especially when the outbreak was in full swing.

"It's not easy, because many small producers or backyard operations still coexist with commercial farms, but I think that the actions and the way of working of the federal government, state governments and producers is a positive step," said USAPEEC's Cruz.

Changes to come

What the Mexican authorities will do is to combine the movement control with certification of Good Livestock Practices (including biosecurity actions) in all poultry farms.

"If the source is OK, the risk is reduced. Even a bad mobilization made with a certified origin reduces the risk. Rather the reverse -- with a poor mobilization made at the source, a state or a region -- can be negatively impacted," says Señas.

Based on the Federal Animal Health Law, the Agrifood, Aquaculture and Fisheries Safety Office of Senasica in Mexico will promote the certification of Good Livestock Practices in all farms by means of certification bodies that comply with certification processes and legal approval.

"Currently, the National Agrifood Certification Body (ONCA), is in such a process for poultry farms. It will take six to eight months to meet the requirements set by law and to proceed with the official certification nationwide" adds Dr. Señas.

Likewise, it is not convenient to put so much pressure on the producer, who is the one who risks the most. Señas noted that "we have to reach a scheme in which the producer is benefiting, as well as institutions and authorities, which are the guarantors at international level." Thus, there will be more legal grounds for banning mobilization.

In the Poultry Plan 2015-2018, UNA wants ONCA to be one of the certified and authorized organizations by Senasica for issuing certificates of good poultry production practices and biosecurity.

Good production practices

Senasica is updating chicken and egg good production practices manuals, which date back to 2009.

"The trend is that each poultry production unit is certified in the appropriate controls and processes," says Señas, so that training must begin there. This involves courses on basic HACCP, 19011 Mexican Standard (audits) and Good Livestock Practices for Third Parties or Authorized People in charge. The accreditation and approval will be by species. "Additionally, we need to provide feedback to the producer and that he/she participates in the process."

Manure must be transported in closed vehicles or in bags, or offense is committed under the current legal framework in Mexico, deserving sanctions. These can range from economic sanctions to criminal penalties. Also, record logs of this product must be maintained.

Need for a contingency fund

Is there a lack of awareness of poultry farmers? "I believe that there is lack of awareness on the part of some, but not all poultry producers," said Chavez, but there is an undercurrent.

UNA is aware of the required biosecurity practices, but at this point we reach to one of the issues, "which is the importance of having a contingency fund," says Chávez. The contingency fund should be a significant sum to compensate poultry producers for losses if the disease has been properly reported. "Right now, when comparing what happens in the U.S., we do not have in Mexico such an instrument," added the CEO of the UNA.

UNA has sought to promote before the Congress an animal production disaster fund, such as the one existing for agricultural disasters.

So far, UNA has been unsuccessful in this regard. Their wish is to have a multi-year fund, that is, if there are no problems in a year, there would be no need to negotiate it in the next year. "We think it ought be a minimum fund of MXN1 billion (US$63 million), for the livestock sector," says Chávez. Otherwise, if it is less, would producers report a problem when you know that the fund is not enough? Fear of no compensation, quarantine, slaughter of birds will always be there. In short: fear of losing business.

Manure commercialization

Processed manure is obviously more expensive than raw. This is a marketing problem that companies will have to solve. For example, avocado growers in Mexico use poultry manure as fertilizer, which puts pressure on the market, but which can turn manure into something more than just a byproduct.

There are other different strategies. In the state of Veracruz, there is a plan to burn the manure in turbines to produce electricity. There is also the use in livestock feed, as a nitrogen source for ruminants.

The use of heat processing equipment depends on the cost/benefit ratio. It must be remembered that industrializing poultry manure means an extra cost, which may affect the competitiveness of the egg producer.

Conclusions

The current avian influenza situation "is a paradigm," said Cruz, "we had not had a situation like this in many years."

We must remember "poultry producers sell chicken and eggs. They do not sell manure," says Chavez, but they are accountable for this byproduct.

"It is the producers' duty to take care of biosecurity, have proper management and not mobilize untreated manure. It is a culture that must be extended throughout the country," said Cruz. "At least the industry of Mexico together with the U.S. (UNA and USAPEEC), in conjunction with the authorities are trying to handle this situation and to have a common strategy in North America (Mexico, USA and Canada), in the common commercial region," said Cruz.