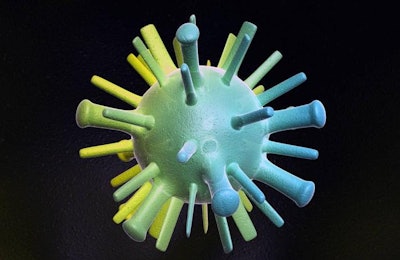

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and state and industry partners are treating the potential threat of more highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) infections in the fall of 2015 with the utmost seriousness.

While researchers at USDA’s Southeast Poultry Research Laboratory are working on new vaccines to protect U.S. poultry from the highly pathogenic H5N2 avian influenza virus, the primary focus is on federal, state and industry efforts to implement tighter biosecurity and streamline outbreak response plans.

Poultry producers are being challenged to implement tighter biosecurity protocols that extend from the farm’s edge to all the poultry farm’s individual structures and internal processes. The heightened internal biosecurity on the farm is a response to an unprecedented, widespread contamination of the farm environment with virus shed by wild birds.

USDA and the states are working together, along with the poultry industry, to expand their capacity to quickly and efficiently depopulate and dispose of poultry mortalities. Lack of depopulation and disposal capacity during the height of the HPAI outbreaks earlier in 2015 resulted in a backlog of infected flocks, causing shedding of greater virus loads into the environment and greater farm-to-farm disease transmission.

Wild birds will likely bring avian flu this fall

“Although we hope that we will not have additional or more widespread outbreaks, it’s very likely that wild birds will carry the virus with them when they begin migrating south in the fall. Although states in the Atlantic flyway have not been affected by this HPAI outbreak, it’s important that our state and industry partners begin preparations should the disease occur there,” said Dr. John Clifford, deputy administrator veterinary services, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS).

Clifford was testifying before the House Agriculture Subcommittee on Livestock and Foreign Agriculture about federal, state and industry preparations underway as the southward migration season of wild birds approaches, putting poultry flocks in jeopardy across the nation.

Planning for future avian flu outbreaks

APHIS has conducted planning workshops with state and industry partners focusing on the worst-case scenarios and the responses needed should HPAI outbreaks occur in the fall. “We’re identifying the resources we would need under various scenarios, and how we can better partner with states and industry to manage this disease,” Clifford told the subcommittee.

“We’ve encouraged our partners to review the existing avian influenza response plans so they understand what we will expect and what actions we will need them to take should the disease strike. Along those lines, we’ve urged states and industry to develop site- and county-level specific depopulation plans for landfilling or composting birds. Our experience in the Midwest showed that the biggest roadblock to efficient depopulation (which is a key to reducing the spread of the virus) is the lack of ready sites to receive and process dead birds,” he testified.

Preparedness for HPAI in North Carolina

Dr. Bill Hartmann, executive director and state veterinarian, Minnesota Board of Animal Health, said in testimony before the subcommittee that the most important lesson learned in the HPAI outbreaks is that building relationships with the poultry industry and state and federal officials before a crisis is crucial. The lesson wasn’t lost on North Carolina officials who sent teams to support Minnesota’s efforts during the height of the outbreaks.

Dr. R. Douglas Meckes of the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services told the subcommittee that his state’s preparedness activities began in earnest after requests for disease management assistance were received from Minnesota in March 2015. The deployments of North Carolina response teams to Minnesota during the crisis became the cornerstones for preparedness in North Carolina.

Quick depopulation of HPIA-infected flocks

Noting that the delay in depopulation of infected flocks contributed to the lateral spread of the virus in the Midwest, Meckes said, “We are determined that inadequate depopulation capability will not cause similar problems in North Carolina.” The North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services has conducted twice-a-month training sessions for staff and others in the use of foaming equipment for depopulation.

Hartmann, in fact, told the subcommittee that depopulation of HPAI-infected flocks needs to occur within 24 hours of diagnosis. “When this is not done the virus quickly infects more birds, which then shed the virus in large quantities creating a heavily contaminated site, increasing the chance for lateral spread. The needed resources include equipment for depopulation and trained personnel. There should be facilities around the state where you can set up an emergency operations center near where the cases are found. Your laboratory must have enough trained technicians and equipment to manage the increased volume of tests. All poultry farms must have an emergency carcass disposal plan. A new level of biosecurity is also necessary to stop the spread of this virus.”

Curbing lateral spread of avian flu

Noting that APHIS has indicated biosecurity is paramount to preventing lateral spread of HPAI, Meckes testified: “Our goal in North Carolina is ‘no lateral spread’ and to accomplish this, the biosecurity lead on each positive farm will ensure compliance with biosecurity procedures by our team members, all grower staff, and for all movements on and off the premise.

“Since North Carolina grower facilities are typically in much closer proximity to one another than in states which have already been affected, there is a greater need for comprehensive biosecurity practices to reduce the risk of HPAI spread. Consider, for example, some identified 10-kilometer control areas in North Carolina’s Animal Health Database have over 500 individual poultry houses within the perimeter. Given that all movement between farms and within farms needs to be conducted under the assumption that the disease may be present, the biosecurity mechanism is monumental but doable.”

Hartmann testified that Minnesota is working with the state’s poultry producers to audit their biosecurity plans.

Composting avian flu poultry mortalities

“Given constraints on burial throughout much of North Carolina and limitations on landfills and rendering facilities, composting is recommended as the first choice for management of poultry carcasses as has been the case throughout the Midwest,” Meckes said. “The compost disposal method is also a preferred biosecurity measure in that no diseased birds need to leave the farm. Rapid establishment of mortality compost windrows on-site is key to disposal of birds and inactivation of the influenza virus. Timely and effective composting also aims to minimize downtime for the impacted farms to the extent possible.”

The department’s disposal work group is working to identify carbon sources across the state in sufficient quantity to develop effective compost recipes on each infected premise. The work group is also developing guidance for land application of finished compost for agronomic use as a soil amendment with fertilizer value.

Partnerships in responding to avian flu

“Should the disease strike in the fall, USDA and its partners will be ready to tackle it head-on,” Clifford testified. “We all have a role in – and a responsibility for – our nation’s agricultural health, and we will work together to ensure that we are in the best position possible to address this disease.”

Fomites, such as equipment, probably played a role in the outbreaks.

A number of producers expressed a suspicion about airborne HPAI transmission and noted very windy conditions prior to HPAI diagnosis.

Lessons from high-path avian flu outbreaks

APHIS has conducted epidemiological investigations and other studies with the goal of identifying transmission pathways of high-pathogenic avian flu. The findings are helping to inform the biosecurity planning:

- Equipment sharing is very common in the poultry industry. Equipment sharing makes economical and logistical sense, but it also increases the risk of lateral spread of HPAI between farms. Fomites, such as equipment, probably played a role in the outbreaks.

- Litter characteristics and carcass disposal may play a role in disease transmission. When litter and carcasses are transported, infectious material may be spread to nearby farms as trucks travel down the road.

- Wild waterfowl are considered the primary reservoir for avian influenza viruses. Other wild bird species vary in their susceptibility to AI and their ability to transmit the virus. For instance, sparrows are highly susceptible to HPAI and can shed virus. Wild birds were observed inside the barns on 35 percent of the farms.

- Airborne transmission is a possible means of spreading the HPAI virus. A number of producers expressed a suspicion about airborne HPAI transmission and noted very windy conditions prior to HPAI diagnosis.

- Several farms noted that birds were being treated for other diseases at the time of HPAI diagnosis, such as clostridial dermatitis and cholera. Therefore, stress may play a role in susceptibility to HPAI.

Seeking to avoid repeat of HPAI outbreaks

USDA – through the APHIS National Veterinary Services Laboratories – confirmed HPAI in 21 states, which includes nine states where it was identified in commercial poultry. The disease was confirmed in 232 poultry premises, with 211 of those being commercial facilities. As part of our disease control strategy, USDA depopulated 7.5 million turkeys and 42 million chickens and pullets. This is approximately 3 percent of the U.S. annual turkey production, and approximately 10 percent of the egg-laying chicken population, Clifford testified.

More than 400 USDA staff and nearly 3,000 USDA-contracted personnel worked around the clock at one time or another in every affected state on the response. USDA delivered over $190 million in indemnification payments to producers. Should the need arise APHIS has the authority to request even further spending, Clifford said. All told, USDA has committed over $700 million – an amount more than half of APHIS’ yearly discretionary budget – in addressing the outbreak.

"Federal, state and poultry industry leaders are putting in place new, higher biosecurity protections for U.S. poultry ahead of the fall wild bird migrations."

"Poultry producers are being challenged to implement tighter biosecurity protocols that extend from the farm’s edge to all the poultry farm’s individual structures and internal processes."