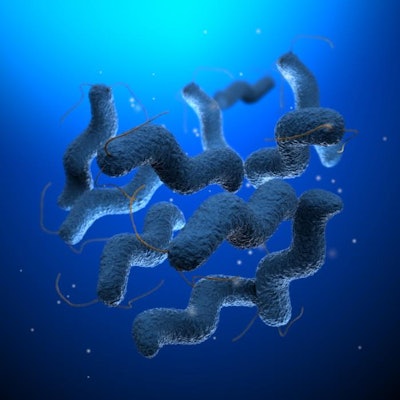

Campylobacteriosis remains the most commonly reported foodborne disease in the EU and has been so since 2005. The latest available data states that the number of confirmed cases in the EU in 2014 was 236,851. Broiler meat is considered to be the most important single source. In 2014, 38.4 percent of the 6,703 samples tested were found to be Campylobacter positive. Campylobacter was found in 30.7 percent of the 13,603 broiler units tested, but variation between EU countries was high. The aim is to reduce colony-forming units (CFU) on whole birds – the indication being less than 1,000 CFU per gram on neck/breast skin.

The primary source of Campylobacter is feces from livestock, in particular, poultry. Other sources are feces of pets, rodents, wild birds or insects, as well as dead birds, beetles or flies. In terms of poultry production, people, tools, equipment, the water supply, rodents or insects can all transmit Campylobacter. Risk factors include unrestricted access by people, ventilation inlet areas, holes in buildings, open doors and windows.

Recent rsearch projects have focused on interventions on the farm and during processing to reduce the levels of Campylobacter. This article explores the application of biosecurity, processing and novel intervention measures useful in reducing Campylobacteriosis rates.

Biosecurity measures

CamCon projects, which ran until April 2015, aimed to improve the control of Campylobacter in primary poultry production in various parts of Europe, thereby enabling the production of “low-risk broilers.”

According to Dr. Mogens Madsen, one of the scientists involved in the project, “there is no silver bullet for Campylobacter. Reducing levels will take concerted effort from the whole industry to influence many risk factors.”

Best-practice manuals have been developed for broiler producers and include advice on the use of hygienic barriers in poultry houses.

An intervention on Spanish broiler farms looked at the effectiveness of these, along with training on entry and exit procedures. The hygienic barrier consisted of first dividing the anteroom in two zones: the dirty zone (the part of anteroom closest to the outer door), and the clean zone (the part closest to the door leading to the broiler room). In the dirty zone, farm personnel removed outerwear and footwear, and washed and disinfected their hands. Once in the clean zone, they put on working clothes and footwear dedicated for each specific broiler house.

This work highlighted the limitations of some broiler house designs, the importance of hands-on training for farm personnel, and the need for supporting materials.

Farming practices and climates vary across Europe, so risk factors are different for each.

Controlling fly contamination

Biosecurity measures, including the use of fly screens, were being evaluated. Madsen predicts that “flies may be more important for Campylobacter transmission in dry countries, like Spain, than in Northern Europe, where the climate is temperate and environmental contamination is more of a challenge.”

However, fly screens only work if biosecurity is maintained at house level and may have more of an effect in the summer when flies are active outdoors.

In 2016, CReSA Research Centre for Animal Health’s Marta Cerda-Cuellar presented initial findings at the CHRO2015 Congress. A field study on 18 Spanish broiler farms was carried out over 12 rearing cycles. On 12 of the farms, biosecurity measured were improved and, on five of these, the use of fly screen was employed. The remaining seven farms served as controls.

“The results so far are promising,” states Cerda-Cuellar. “There was a significant reduction in Campylobacter-positive samples on farms with improved biosecurity, which was more marked where fly screens had also been used.”

Factory recommendations

Mary Howell from the Food Standards Agency (FSA) suggests several methods to control the level of Campylobacter in poultry, adding that “these are ideals and not all of the measures will be practical for every situation”:

- Campylobacter should be identified as a specific hazard in slaughterhouse HACCP plans

- Send even-sized birds to the slaughterhouse by employing sexing and an effective cull policy

- Don’t thin – this is a major risk for introducing Campylobacter

- Slaughter at a younger age (this thought to be why some EU countries have lower levels)

- Ensure catching equipment is thoroughly clean

- Withdraw feed eight to 10 hours before slaughter

- Aim for clean feathers and feet

- Consider the effect of stunning method on bird cleanliness

- Maintain temperature in the scalding tank and minimize foaming

- Minimize air flow during plucking

- Get evisceration settings right for carcass size

- Set and maintain standards for fecal and bile soiling of carcasses

- Optimize carcass washing

Processing innovations

Rapid surface chilling units can be installed in-line at poultry processing facilities. The surface of the skin is super-cooled using liquid nitrogen vapor, killing the bacteria. However, the temperature under the skin stays higher than -2C, in order to meet poultry meat marketing council regulations.

When carcasses spend 20 to 30 seconds in the tunnel, levels of Campylobacter are well below the 1,000 CFU per gram target, compared with 15,000 for the contaminated controls. It is also important that there is no regrowth of the bacteria, which can occur after organic-acid treatment, for example.

Novel interventions

Bacteriophages are viruses that infect and replicate within bacteria. They are specific to their host and, therefore, have the potential to be effective antibacterial agents. An in-vitro investigation applied Campylobacter jejuni to chicken skin and treated it with increasing doses of bacteriophage (PFU/cm2).

A decline in Camplylobacter counts were seen following storage at 4C. This reduction was significant in does B-D demonstrating the potential application of bacteriophages to control Campylobacter on broiler meat. Bacteriophages have also been fed to broiler chickens as both preventative and therapeutic treatments for Campylobacter under experimental conditions.

Their application delayed rather than prevented colonization by Campylobacter, in the first instance. Therapeutically, bacteriophages significantly reduced caecum counts of Campylobacter.

Reducing the risk

To reduce Campylobacter levels, each link in the poultry supply chain needs to be involved. Research into prevention is yielding interesting results and increased monitoring shows where interventions are working.

Sustained biosecurity controls deliver improvements, but making an impact involves a step change. It has been ascertained that basic biosecurity measures, at individual house level, reduced the risk of colonization by 50 percent.

Processors are implementing novel methods as well as optimizing control measures to reduce cross-contamination. The use of these measures is assumed to reduce the number of birds highly contaminated by half. Therefore, if farm and slaughterhouse best practices were followed, only one in 10 birds would be highly contaminated. It is estimated that achievement of this target could mean a reduction in Campylobacter food poisoning of up to 30 percent.

Each area faces its own challenges, but it is imperative that all stakeholders work together to achieve the goal of Campylobacter-free chicken