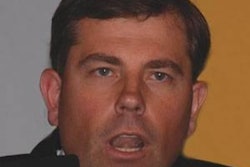

Marcus Rust, executive vice president of Rose Acre Farms, represents the third generation of a family-owned enterprise with over 22 million hens. Egg Industry had the opportunity to discuss the current status of U.S. egg production and future trends with this egg industry leader.

Egg Industry: Please recount for our readers how Rose Acre Farms has become a major world-class egg producer with a significant share of the U.S. market.

Marcus Rust: Our enterprise was established by my grandparents who had about one thousand hens and were the biggest producers in their county in the early 1940s. The seasonal slump in the market price of eggs in spring as hens came into production resulted in the practice of feeding eggs to hogs since traders would not buy them. Instead of throwing away eggs my grandfather had my father take them to market in Indianapolis together with other farm produce. He found a ready market and a local Indianapolis store owner with six stores asked him to return the next week and bring more eggs to his stores and some other retail outlets. This pattern snowballed and it became obvious that eliminating middlemen at the county level and establishing a relationship with city distributors created a more even marketing situation favorable to small operators. Our family started to collect eggs from numerous small local producers and these were hand-candled, graded and sent to market.

EI: When did the family commence production?

MR: The first house was built in 1953 and held 5,000 hens on the floor. By 1960 we had 70,000 hens and by 1964, 240,000. In 1965 we built our first cage house for 100,000 hens. Mechanical collection was extremely inefficient and a number of systems were tried before we achieved success. In 1967 we built our first in-line operation with 100,000 hens and installed a 35 cph Eggomatic grader. In 1972 Jen Acre Farm was erected holding 1.2 million hens. This was followed by the Cort Acre complex which we started in 1977 and completed in 1981, eventually holding 2.4 million hens. We continue to expand looking for higher priced market areas with grain production and consumer demand. Higher energy prices and nutrient input costs for grain and soy production are going to change the location of the production facilities in the future.

EI: Was it just plain sailing?

MR: No. We had our problems. Shortly after completion of Jen Acre Farm the packing plant burnt down together with two adjacent houses. We experienced legal problems with an antitrust predatory pricing lawsuit and in 1990 we unfortunately encountered SE which resulted in extensive litigation with the USDA which is still undergoing appeals. Misfortunes and adversity strengthened our resolve and provided valuable experience going forward.

EI: What are the significant challenges facing our industry today?

MR: Feed and transportation costs are the most important but this is a reflection of factors which cannot be controlled by egg producers. International market demand for grains and diversion of corn to ethanol both play a role. Other factors of concern include the welfare situation and environmental restrictions.

EI: What changes do you see as a result of higher feed cost?

MR: I believe we should consider shorter cycles since the return from hens during the terminal part of their first and second production periods is low in relation to feed consumption. We should also consider obtaining greater value from sale of manure. Right now with the price of fertilizer, poultry manure is worth up to $130 per ton based on nutrient content and capacity to improve soil texture and crop yield. It is evident that we also have to control the supply of eggs since over-production inevitably results in a drop in realization.

EI: Rose Acre has traditionally been strong in breaking and processing. What are the prospects for this segment of our industry?

MR: In the 1970s, 12 percent of eggs were broken compared to slightly more than 33 percent at the present time. It is my opinion that 50 percent of eggs will be marketed in other than whole shell form by 2020. We will have to develop new products and expand the demand for existing items. For example deviled eggs are a delicacy served at receptions and picnics. We need to find a way to incorporate deviled eggs and other presentations for quick service restaurants. The contribution to demand by the major chains offering breakfast menus has helped considerably with disposal of medium grade.

EI: We are recording increases in floor and non-confined production. Expansion has been rapid but over a small base. Do you see this trend continuing?

MR: It's strange that when we started in the egg industry we were all on the floor and then we went to cages and now we seem to be reverting. Sure, there is a market for cage-free product and the industry will respond by installing suitable floor systems in old houses equipped with obsolete cages. We have available technology from U.S. broiler breeders and can draw on experience from Europe.

EI: How about organic production?

MR: Cost will be an important limiting factor. Personally I feel that organic production is incompatible with an in-line operation which presumes high efficiency and extreme biosecurity. Introduction of a disease into a multi-age complex without being able to resort to treatment will create problems. Organic production in the future will be derived mostly from small family-owned units or from contractors supplying a company operating an off-line plant.

EI: As one of the largest egg producers how do you view the oligopoly in the supermarket industry?

MR: There are obviously advantages and disadvantages. There is a convenience factor in delivering large quantities to a regional distribution center. On the other hand, supermarket chains are demanding higher standards including delivery of eggs within three to five days of production. Supermarket buyers are also concerned over price fluctuations since they have a need for stability which contributes to their ordering and forecasting.

EI: Are there additional untapped markets for shell eggs in the U.S.?

MR: I re-emphasize what I said previously about shorter cycles. We are obviously not getting a premium for all of the Extra Large and Jumbo eggs produced at the ends of the two laying cycles. There are many consumers, including Hispanics and especially the elderly or overweight, who would rather eat two medium eggs than two large or extra large. Restaurants also like this as it cuts unit costs slightly.

EI: Rose Acres is the only large company to have established a completely new complex within the past few years, why did you choose coastal North Carolina?

MR: We selected the site on the basis of proximity to markets, a long distance from other egg operations, optimizing biosecurity. The fact that the sandy soil was poor in nitrogen suggested that disposal of manure would not be a problem. The citizens of Hyde County were extremely receptive and supported our application despite opposition in the State Capital. North Carolina and Virginia are basically in deficit when considering egg production in relation to potential consumption. All these factors played a role in our decision to establish what will eventually be a 4-million hen complex.

.jpg?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=crop&h=167&q=70&w=250)