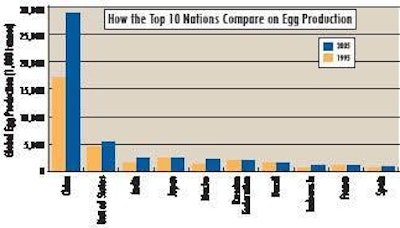

China, the world's No. 1 egg producer has boosted output 67.8 percent over the past decade. India, No. 3, is up 66.6 percent, with Mexico, No. 5 on the list of the largest egg producing nations, up 83.3 percent. This growth illustrates how rapidly the developing world is gaining egg production market share over the developed world, according to 1995 to 2005 data recently released from the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations.

Looking at the developed world, meanwhile, production in the United States, the world's No. 2 egg producing nation, was up 20.7 percent over the period; Japan, No. 4, was down 3.4 percent and the only top 10 egg producing nation to lose production over the period. Looking at Europe, France as No. 9, was up a modest 2 percent over the period. (For a look at other nations, see chart.)

Global egg production has been exploding in recent decades, tripling since 1970 and, "Within a few years the production volume will be higher than that of beef and veal if the growth rates remain fairly constant," according to Hans-Wilhelm Windhorst, in his report Patterns of Egg Production and Trade for the International Egg Commission (IEC). Windhorst, the IEC's statistical analyst, says in the spring 2007 status report that developing nations surpassed developed nations in egg production in the 1990s and now have a 67.7 percent global production share.

But egg production in the developing world "has been very imbalanced," Windhorst says. "The only winning continent was Asia. North and Central America lost considerable amounts of their former market share," he says. Europe was still the No. 1 continent in egg production in 1970, but lost this title in the early 1980s. In 2005, Asia had 60 percent of global egg production, Europe's share had fallen to 16.8 percent, and North and Central America to 13.6 percent. Windhorst says that North and Central America, which had been able to gain higher market shares until 1990, "have not been able to hold their position in spite of an almost continuous growth of the production volume." He notes that regional concentration of egg production is higher than in poultry meat production.

In 2005, the top 10 egg producing nations were responsible for 72.4 percent of egg output. In addition, in 1970, six European nations were among the top 10 in hen egg output and now, only France remains. Replacing the European nations are India, Mexico, Brazil, Indonesia, and Turkey. In 1970, just one of the top 10 egg producing nations was a developing nation, China. Today, six are, with four in Asia and two in Latin America. In 2005, nearly half of global egg production was in China, India, and Japan. "This further documents the regional shift of egg production from Europe to South and East Asia," Windhorst says.

Imports and Exports

In contrast to poultry meat, in which 12 percent was exported in 2004, only 1.8 percent of hen eggs were traded on the world market because it is difficult to transport shell eggs over long distances and most eggs are traded within small regions, Windhorst says. Egg exports have increased from 400,000 tons in 1970 to more than 1 million tons in 2004.

In 2004, European export volume was about 68 percent, down from almost 82 percent in 1990. Developing nations' share has fluctuated between 10.5 percent and 24.5 percent from 1970 to 2004, indicating both increasing production output in several developing nations and showing that most of the consumed eggs stem from domestic production, Windhorst says. North and Central American exports have increased.

In 2004, the Netherlands and Spain ranked as the No. 1 and No. 2 exporting nations, together accounting for 35.4 percent of all global export volume. China was No. 3. Several countries not among the leaders in 1970 were by 2004, including Spain, the United States, Malaysia, and India.

Windhorst says that the "egg trade is to a high degree a phenomenon between European as well as Asian countries. Nevertheless, Africa has become a more attractive market during the last decade." Thus far, South American nations are not playing a significant role in the global egg trade. North and Central American nations mostly trade eggs among the three North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) members.

Germany is Leading Importer

By far, the world's largest egg importer is Germany. One fourth of all traded shell eggs were imported by Germany in 2004, down from one third in 1970. The import volume would have increased to about 10 to 11 billion eggs starting in 2012, Windhorst says, had Germany not changed the national directive of October 2001. That directive would have banned conventional in addition to enriched cages. With the change of administration in 2005, initiatives were started to develop a new directive and permit so-called small aviaries. This directive was approved by the government last year.

Windhorst says that even though the regulations are stricter than those of the European Union for enriched cages, "the industry is more optimistic about the futures of German egg production. Nevertheless, the regulations may have far reaching impact on the number of laying hens as the directive demands that the aviaries have to be at least 60 cm high and the lower aviary be 35 cm above the ground. If one calculates that about 25 cm per layer are needed for the installation of manure belts, then only two layers of aviaries can be installed in existing hen houses which formerly held three to four conventional cages."

Windhorst says that "what impacts the full implementation of the German directive and of directive 1999/74/EUwhich bans conventional cages from 2012 on and demands enriched cages in new facilities from 2003 onwill have on the egg trade is still an open question. It can, however, be expected that the EU will at least from 2012 on no longer be an egg surplus region."

Interesting to note, Windhorst says, is that while developing nations bypassed developed nations in global egg production market share in the 1990s, their contribution of export market share is still far lower.

U.S. Export Outlook

In light of European cutbacks, can the United States increase egg and egg product exports over the next few years? "I think that only a moderate increase of exports will be possible," Windhorst tells Egg Industry. This could, however, change if the EU market would be open for egg products as a result of the World Trade Organization negotiations. The EU would then be an attractive market for egg powder. "Most of the EU egg products' companies are afraid that this may happen, as production costs in the United States are much lower than in Europe," he says. The cost of the production gap will open even wider as a consequence of the foreseeable abandoning of conventional cages by 2012, in Germany even in 2009, Windhorst adds.

The United States was not among the top 10 egg exporting nations in 1970, but by 2004, was No. 5 with a 6.9 percent market share. On production, the United States was the largest egg producing nation in 1970 with a 20.7 percent market share. By 2005 the United States had slipped to No. 2 with a 9 percent share market share, with China emerging as the world's largest egg producing nation.

China's Role

China is the main reason why developing nations have 67 percent of global egg production, Windhorst says. China alone had a 41.1 percent world production market share in 2005. Without China, egg production in developing nations increased only until 1990. Since then it has remained around a 27 percent market share, or even decreased. Without China, egg production in developed nations has recently been growing at least as fast as in developing ones.

Avian Influenza

Windhorst says, "The remarkable dynamic of the poultry industry could, however, come to an abrupt halt if the spatial dissemination of the Avian Influenza (AI) virus cannot be stopped." Outbreaks in Europe and Africa in the first quarter of 2006, "had the result that consumers refrained from eating poultry meat and eggs," he says. Windhorst adds that one can assume that an outbreak of AI in the United States or an EU member state would have far reaching impacts on egg consumption.

But that said, Windhorst notes that in South and East Asia, with the exception of Thailand, the impact on the egg industry by AI was very limited. "Quite obviously, the egg industry was much less affected than poultry meat production, in which volume decreased considerably and Thailand's export volume of poultry meat dropped by almost 90 percent between 2000 and 2004."

Thailand's egg exports dropped by 60 percent between 2000 and 2002, then recovered by 2004, although the former volume was not regained. Vietnamese exports remained relatively stable until 2002, decreasing by 42 percent until 2004, but China was a different story. Chinese egg exports increased by 32.5 percent during the same time period despite AI outbreaks. India, meanwhile, which had no outbreaks, was able to increase its egg exports by almost 330 percent.

In Europe, egg exports in the Netherlands declined by 24 percent between 2002 and 2003 after an AI outbreak, and by 70 percent in Italy between 2003 and 2004, also following an outbreak.

"Quite obviously," Windhorst says, "the outbreaks of AI had not only severe impacts on the domestic consumption of poultry meat and eggs but also affected export volume. On the other hand, countries without outbreaks could profit from this situation and increase their exports, which is especially true for India."