There’s a new sheriff in town when it comes to how USDA approaches food safety and, especially, salmonella in poultry. Just check the following comments made by USDA’s Under Secretary for the Office of Food Safety: “Everybody needs to understand that there’s going to be changes in how the Office of Food Safety and the Food Safety and Inspection Service approach this important issue of reducing salmonella,” said Richard A. Raymond, a former director of the Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services Regulation and Licensure Division, who along with several other Nebraskans followed Agriculture Secretary Mike Johanns to Washington for the second term of the Bush Administration.

“You probably heard in 1996, when the [Pathogen Reduction/Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point] rules were published, that it was the goal of FSIS to lower salmonella rates. I don’t think that ever happened. You’re hearing it again, but it’s a new world; we’ve got a new Administrator, a new Deputy Administrator, a new Under Secretary and a new Secretary, and we believe strongly that this is going to happen this time. And we’re going to tell you how, and we’re going to tell you why,” Dr. Raymond said.

Tough talk from a high ranking official, who made the remarks not for the TV cameras or press but to poultry industry members gathered in Atlanta earlier this year to learn about the agency’s comprehensive initiative to reduce the presence of salmonella in raw meat and poultry products. Speaking bluntly at the meeting to any who doubted the agency’s determination to reduce the pathogen, Dr. Raymond said, “And so when you say, ‘I don’t think we can do better with salmonella,’ suck it up. We’re going to do better with salmonella.”

What has riled agency officials is that since 2002, FSIS has seen an increase in salmonella-positive samples in broilers. “My first day on the job, Secretary Johanns told me this should be one of my top priorities: To get our arms around salmonella and lower those rates and protect the public. And believe me, it is one of my top priorities, and we will get this done,” Under Secretary Raymond said.

11-Step Initiative

FSIS announced 11 steps in its initiative, and agency officials say they will be employing a carrot-and-stick approach in dealing with the industry. For now, FSIS is wielding the stick and only hinting at a possible carrot – increased line speeds for the best performing plants – later, if the initiative produces the desired result.

Keeping the pressure on poultry processors is a key to the plan. The FSIS initiative includes concentrating resources at establishments with higher levels of salmonella and changing the reporting and utilization of FSIS salmonella verification test results. The effort is patterned after the FSIS initiative to reduce the presence of E. coli O157:H7 in ground beef. The FSIS E. coli O157:H7 initiative led to a 40 percent reduction in human illnesses associated with the pathogen, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Raymond and others in the agency say a central factor in the E. coli O157:H7 model’s success was a collective acknowledgement by industry that this food safety hazard needed to be addressed in all their food safety systems.

Where FSIS has performed Food Safety Assessments (FSAs) in poultry processing plants that have persistently poor performance records for controlling salmonella, there has been a dramatic reduction in the levels of salmonella, according to the agency. These results, officials say, have demonstrated that establishments can control the incidence of salmonella in the raw products they produce. FSAs are comprehensive, systematic evaluations of a firm’s food safety system performed by Enforcement, Investigation and Analysis Officers (EIAOs).

Speaking of the FSAs, Raymond said, “We had one plant that had a 30 percent rate on the performance set. We did a food safety analysis, and we worked with that plant to point out areas that they should and could improve. In the next set we went in, they had a 2 percent. Now that is dramatic. What we need to do is to move the trends that direction in all of our plants that are in the poultry business. That’s our goal. I firmly believe that we can get that done.”

But officials also say the agency is now willing to share information with the industry in ways that did not occur in the past. According to the strategy, which is described in a Federal Register notice published in February, FSIS will now provide the results of its salmonella-performance standard testing to establishments as soon as they become available on a sample-by-sample basis. This, say agency officials, will enable establishments to more readily identify and respond to needed process control in the slaughter-dressing operation. Receiving individual sample results soon after the samples are taken is intended to help establishments in their assessment of whether their slaughter procedures are adequate for pathogen reduction.

Before the initiative, establishments received results after the sample set was completed (for broilers a sample set consists of 51 consecutive days of sampling). FSIS will also begin quarterly posting on its Web site of the nationwide aggregate results of all sample results to give consumers more complete and timely information about salmonella trends. The postings, say officials, are to provide consumers with information about overall industry performance in protecting public health.

USDA seems poised to ratchet up the pressure even further on the industry if meaningful improvements don’t occur. Raymond alluded to the possibility that the agency might consider posting results from salmonella performance sets and identifying those results by plant. While industry leaders have not made public statements about such a move, it is not one likely to be welcomed by the industry.

Dr. Raymond explained the rationale behind the possible move: “I know that if I go to a restaurant tonight and eat a chicken breast, I don’t know which plant it came from, and I don’t know what the performance sets were. Now, the consumers want to know that. They want to know who’s up there in that top 30 percent, and they want to know who’s down there in that bottom 30 percent. And we haven’t done that. But it’s one of those little carrots and sticks that you’re going to hear about that we may entertain if we can’t get some movement within the industry to get the 30 percent coming on down so they more closely mirror the ones with the good performance sets.”

FSIS also plans to more quickly have the serotype of salmonella found in positive samples determined in order to notify the establishment and monitor and investigate illness outbreaks in coordination with federal, state and local public health agencies. These results, they say, could provide useful information about trends in the presence of serotypes of salmonella in order to prevent human disease.

Performance Categories For Plants

In the initiative, FSIS has established three plant performance categories that will, among other things, determine the level of scrutiny the plants receive from the agency. Plants in the best performance category (fewer than six salmonella-positive tests in a 51-sample set) would theoretically receive less scrutiny than plants in the poorer performing categories.

Category 1 plants, those with less than six positive tests out of a set of 51, have less than or equal to 50 percent of the performance standard set by FSIS. These plants, say agency officials, demonstrate that consistent salmonella control is possible.

Category 2 plants, those with between seven and 12 positive tests, are operating at a salmonella incidence level greater than 50 percent of the FSIS performance standard. These plants, FSIS says, can improve salmonella control with assessment, guidance and verification. Plants in this category can expect to receive more intense FSIS scrutiny.

Category 3 plants, those with 13 or more positive tests out of 51, are exceeding the performance standard.

Agency officials say the goal is to get 90 percent of establishments in Category 1. FSIS reports that, so far, in the seven years of performance testing, 25 percent of plants have always had results below one-half of the performance standard (equivalent to Category 1). At the same time, 45 percent of the plants have never exceeded the performance standard. Thirty percent of the plants, however, have at times exceeded (or failed) the performance standard.

Human Health Component

One measure that FSIS will be watching is in human health. Dr. Raymond reminded listeners in Atlanta that 14.5 people out of every 100,000 Americans get sick with culture-proven salmonella every year. “CDC estimates it’s actually 1.3 million people a year that get sick with salmonella; they just don’t get sick enough to get a stool culture. And 400 people die with salmonella,” he said. While not every case of human salmonella is from poultry, Dr. Raymond says the agency is counting on reductions in salmonella in poultry products to help bring human sickness levels down.

The Under Secretary pointed to the government’s Healthy People in 2010 goal of 6.8 infections per 100,000 people. With the current level of salmonella infections at 14.5 people, there is a ways to go, he noted. “It’s going to take awhile, but we’ve got four years to get to the Healthy People goal for 2010,” he said.

Meantime, this expectation can be expected to have practical ramifications for industry plants. FSIS reports that common human salmonella serotypes are significantly more likely to occur in Category 2 and 3 performance sets. Categories 2 and 3 sets accounted for only 32 percent of sets but 63 percent of common serotypes of human illness. Officials have indicated that monitoring and verification (selection for additional testing, FSAs, etc.) are to be based not just on process control but influenced also by the kinds of serotypes being found in testing. The existence of human serotypes in samples from a plant can be expected to draw more agency attention.

How Can Salmonella Be Reduced?

Can the agency bring the approach that worked to reduce E. coli in beef to the poultry industry and make it work for salmonella? Clearly, in the initiative for the poultry industry, agency officials are relying on lessons learned in the beef industry.

Agency officials are relying heavily, for example, on the industry reassessing its food safety programs. While officials expect the poultry industry to take the initiative in reassessing the programs at plants, the agency plan is to assure that this reassessment is occurring through the administration of Food Safety Audits at plants, especially those plants in Categories 2 and 3.

In comments made in Atlanta, FSIS Administrator Barbara Masters pointed to the beef industry experience. “The industry-wide initiative of reassessing their programs is when we saw drastic changes industry- wide. We believe that the poultry industry can see similar changes if they apply a comparable model,” Masters said.

At the same time, Dr. Masters indicated that there’s recognition at the agency that there can’t be a one-size-fits-all approach. “We understand that plants are using a variety of ways to control salmonella, and there are a lot of different ideas and approaches to controlling salmonella,” the administrator said. She added, “Look at your own plant environment, reassess your program and figure out what works best in your plant environment.”

In order to aid these reassessments, FSIS is to release a new set of Compliance Guidelines for salmonella reduction based on a comprehensive review of the scientific literature.

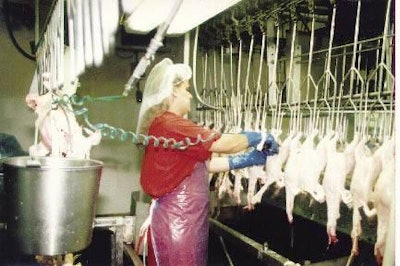

The agency is also putting emphasis on process mapping in poultry slaughter systems in support of multiple-hurdle approaches to reducing salmonella. Process mapping, or line profiling, is sampling at selected points in the process where contamination levels can be assessed for the purpose of evaluating the efficacy of interventions. It’s a tool that can help plants judge the effectiveness of interventions in operations and determine how to proceed with improvements.

In talking about process mapping, Dane Bernard, vice president of food quality and quality assurance at Keystone Foods, said, “So why go to all this trouble? . . . It really was not until we began to do this type of study in the beef industry that we began to have a baseline by which we could judge the effectiveness of the interventions, by which we could judge whether the interventions were themselves not working or whether it was a certain other part of the process before the intervention that wasn’t working.”

Dr. Bruce Stewart-Brown, vice president of food safety and quality for Perdue Farms, put the process of evaluating interventions in perspective. “What we’re trying to do is find four or five different ways in the plant to get 50 percent reductions in the incidence of salmonella,” he said. Given that no practical and affordable method is available to enumerate salmonella on carcasses, Stewart-Brown postulates 100 percent prevalence on incoming birds. (While this level may be higher than experienced in certain plants or at certain times, the supposition is useful for planning a system that works in every case.) In his assessment of a multiple-hurdle approach, Stewart-Brown contemplates a stepwise series of interventions, each yielding a 50 percent reduction – from 100 percent to 50 percent, from 50 percent to 25 percent, from 25 percent to 12.5 percent, and from 12.5 percent to 6.25 percent.

Given that at the picking step, there is apt to be a 50 percent increase in incidence on carcasses; Stewart-Brown said five places to get 50 percent reductions are needed to assure that salmonella levels are brought to an acceptable level. Stewart-Brown noted that currently the most effective salmonella reduction steps are the scalder, OLR and post-chill dips or sprays. Much work, therefore, has to be done in finding the adequate number of effective interventions.

During the two-day conference in Atlanta, speakers from industry, academia and government addressed various intervention steps. One of the speakers, Robert O’Connor, director of quality and food safety for Foster Farms, reported on a validation study involving five of a plant’s process steps. At the first process step studied, the New York wash, a 30 percent incidence of salmonella was reduced by about 10 percent. At the inside-outside bird washer (IOBW) No. 1, the salmonella incidence was cut in half. The salmonella incidence at IOBW No. 2 was reduced only marginally. At the online reprocessing cabinet, where TSP was in use, the salmonella incidence was reduced from a level of 16 percent to a level of 4 percent. At the chiller, where chlorine and CO2 for acidification were used, a 6 percent salmonella incidence dropped to 3 percent. Based on the study, Dr. O’Connor concluded that the greatest reductions in the incidence of salmonella at the plant came at the online reprocessing cabinet and the chiller.

As an aid to evaluating intervention steps, several speakers commented on the need for an inexpensive means to enumerate salmonella. Dane Bernard remarked that it costs about $200 to $300 per sample, using the MPN method, for a reliable salmonella enumeration. “It simply doesn’t lend itself to the type of online controls or quick turnaround that we would like to have to be able to better assess our processes.” He noted than some new enumeration technologies are under development.

A number of interesting points were raised during the question-and-answer sessions held during the conference. One participant observed that due to FSIS plans to focus more testing in plants in Categories 2 and 3, the data can be expected to register a continued rise in salmonella incidence due to sampling bias. In response, Deputy Assistant Administrator Dan Engeljohn revealed the agency’s intention this year to launch another national baseline study, which is to be statistically designed.

Other participants challenged the agency’s presumption that the rise in the incidence level of salmonella in the past three years was solely plant related. They suggested the possibility that the rise was influenced by increased salmonella incidence in live birds. Such a rise, they postulated, might be brought about by the discontinuance of the feeding of non-therapeutic antibiotics by a number of poultry companies.

As the meeting drew to a close, Dr. Engeljohn encouraged the industry to offer comments about the agency’s pathogen reduction initiatives. “What incentives do you think would provide you the appropriate means to justify the added expense of having a measurable impact on reducing pathogens of public-health concern?” he asked. “If you have concerns other than production volume and you think that there are other things that would encourage you within the industry to expend the resources to have better process control, we want to know what those are. And we’ll find a way to work with you on insuring that our regulatory process is not an impediment to innovation.”