.jpg?auto=format%2Ccompress&q=70&w=400)

The sometimes hyper-expansion of the North American ethanol industry has not been without its growing pains. And with over 10 million tons of distillers grains flowing from plants, the animal feed business has not been immune to the aches and pains of ethanol's formative years. Inconsistency in quality, questions over nutritional values, and getting product to the end user have been recurring hurdles.

Massive quantities

While exact statistics vary somewhat, there is no denying the ethanol boom has resulted in what can only be described as massive quantities of distillers grains. The U.S. Grains Council says that based on the projections of top analysts, the current pre-cellulosic ethanol build-up will continue until the corn dry-mill dominated industry hits the 15 billion-gallon mark, a production level that would yield approximately 17 million tons of DDGS annually.

One look at those predictions and it becomes obvious that there will be market opportunities around the world for beef, dairy, swine and poultry producers, as well as feed manufacturers, to take advantage of the sheer volume of distillers grains. But will the animal feed industry be satisfied with the quality and costs they encounter? Will transportation problems continue to bog down efforts to get the feed where it's most needed? In short, can the ethanol industry deliver?

Growing export markets

Earlier this fall, hundreds gathered in Chicago for the International Distillers Grains Conference which focused on industry issues related to distillers grains produced at dry-mill ethanol plants and marketed to both domestic and international end users. A common theme running through the event was that the U.S. is currently falling well below the potential levels of incorporation of distillers grains in livestock and poultry diets, a situation that is fueling interest in exports.

Most estimates are that about 11 million tons of distillers grains is represented in the collective production capacities of ethanol plants either on line or under construction today. Approximately 2 million tons of DDGs are already being exported annually, but if that part of the business is to survive, that number needs to double or triple. And domestic users could stand to benefit from more consistent quality and improved transport if those export relationships can be solidified. Growth in international market opportunities should spell increased attention on quality and consistency, benefiting all markets.

This is a top priority for companies that make and market distillers grains as they seek to build valuable new relationships in one of the world's fastest growing feed ingredient businesses. Ken Eriksen, senior vice president, transportation services, Informa Economics, told those at the conference that exports of dried distillers grains is only in its infancy. In addition to European destinations, he pointed to new destinations in Asia, including China, India, Japan, South Korea and Bangladesh.

Increasing dietary levels

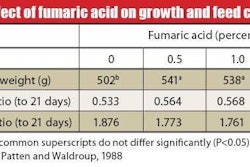

Recommendations vary, but typical inclusion rates of 10 to 20 percent DDGs in animal diets fall well short of levels many feel could be pushed as high as 40 percent in livestock rations. Currently, industry figures estimate that dairy animals consume about 46 percent of available DDGs in the U.S., beef cattle utilize 42 percent, swine 9 percent and poultry 3 percent. But certain nutritional issues have been on the radar of diet formulators from the beginning.

Troy Lohrman, Quality Technology International, Inc., says too much fiber for poultry, pet and aquaculture; too much ‘free' unsaturated fatty acids for dairy and some integrated swine operations; and worry over phosphorus are the most common nutrition concerns with adding DDGs to animal diets, and probably the greatest factors slowing growth in their use.

But while lower-than-maximum inclusion levels have impact, most speakers at the conference pointed to challenges relating to storage and transport as the highest priority issues to be addressed. "DDGS is more challenging to handle, ship and store," noted Lohrman. "Pelleting is difficult and so the product often cakes in transit."

He said one solution to the problem is fractionation, a process which involves separating the oil, fiber and as much of the mineral as possible from the corn prior to fermentation. Lohrman pointed to published benefits of various fractionation processes, including increased ethanol fermentation concentration from 8 up to 27 percent, reduced fiber content of protein mass from 11 percent to as low as 2 percent, and an increase in co-product protein content from 28 to 58 percent.

"Certain traditional dry-grind DDGS has certain nutritional limitations in monogastrics," Lohrman said. "Today's corn-ethanol fractionation technologies will allow more feedstuff options for nutritionists, create more specialized feed products for different species, lower feed ration costs and improve logistic and handling issues relative to DDGS."

Pelleting is potential solution

Leland McKinney, Department of Grain Science and Industry, Kansas State University, also spoke at the conference and addressed concerns of storage and transport. "Pelleting DDGS is a potential solution to transportation and storage difficulties, but conditioning temperatures and residence times are key," he noted.

McKinney maintains that relatively good quality pellets can be achieved from 100 percent DDGS and that it doesn't take the perfect pellet to see payoffs in terms of maximizing bulk density for transport. Factors such as formulation, conditioning, particle size, pellet die, and the cooling and drying processes all contribute to quality in pelleting distillers grains. Opinions as to success of the pelleting process varied widely among speakers, although most agreed with McKinney that conditioning temperature and residence time in the die can be the biggest factors in obtaining good quality pellets. While many feel the process holds promise and several companies are finding success in pelleting, at least one speaker described how pellets simply fell apart shortly after the pelleting process so that by the time they reached the point of storage and transport, it was impossible to tell they had been pelleted at all.

Outlook positive

Despite issues of storage and transport, many at the conference were upbeat over the potential growth in distillers grains markets. Scott Richman, senior vice president, Informa Economics, notes that while export markets are getting a lot of attention, the vast majority of production increase to date has been domestic use. How large that domestic market will continue to grow will be determined by future inclusion rates. "Over the intermediate to long-term, exports will rise significantly as production nears the potential market size and ethanol facilities are built in position to export," Richman noted.

But he said there will be some constraints to expanding export markets. In the near term, that includes a biotech issue with the European Union. Longer term, he identifies transportation costs, continued difficulty with the product "setting up" during transport, inconsistency, availability and further development of foreign markets, understanding of product usage and value, and government approval and registration as the largest factors shaping future export markets.

McKinney perhaps summed up the thoughts of many at the conference. "As ethanol production evolves, the resultant DDGs will also evolve," he said. It appears the ethanol industry is now paying much more attention to the animal feed market, both domestic and international, a sign perhaps that the evolution has begun.

.jpg?auto=format%2Ccompress&crop=faces&fit=crop&h=48&q=70&w=48)