The U.S. egg industry was exposed to extremely adverse publicity following the mid-August 2010 egg recall due to Salmonella enteritidis. The immediate effect of media attention was a precipitous drop in prices due to an immediate decline in consumption, mirroring the UK’s late 1980s “Eggwina” episode, when a Junior Health Minister’s warnings over infected eggs lead to a rapid decline in egg sales.

The U.S. recall involved almost half a billion eggs through 11 states. It is estimated that the $0.40 per dozen decrease between the projected benchmark price and actual realization, cost the generic shell-egg industry over $100 million in September 2010 alone. Although by mid-November market prices had been restored to pre-recall levels, the incident, coupled with the July 1 introduction of the Final Rule on Salmonella by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, has influenced the approach of the industry to Salmonella enteritidis infection.

Emergence of Salmonella enteritidis in the U.S.

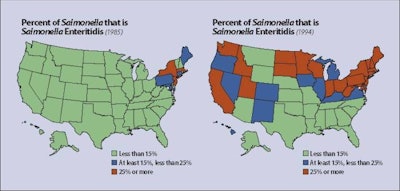

The index outbreak of Salmonella enteritidis in the U.S. occurred in 1979 in the New England states, essentially emanating from one large complex in Maine. During subsequent years, cases emerged in the Mid-Atlantic region and, by 1994, most states had reported outbreaks.

The U.S. has an extensive surveillance system for Salmonella and other food-borne diseases, known as FoodNet. The FoodNet system incorporates 10 participating state health authorities, the Food and Drug Administration and the U.S. Department of Agriculture. FoodNet has become progressively more inclusive, and by 2005 covered a population of 45 million. Concurrently, the PulseNet system was developed to apply pulsed field gel electrophoresis assays to attempt to relate isolates derived from patients with possible sources of infection.

The introduction of egg quality assurance programs, especially in Pennsylvania and California, coupled with vaccination of flocks and improved biosecurity, reduced the incidence rate of SE outbreaks from 85 in 1990 to a plateau of 30 cases per year in the late 2000s.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that there are 110,000 cases of egg-borne Salmonella enteritidis infection among consumers annually in the U.S., based on approximately 5,300 reported confirmed cases with application of a multiplying factor of 38. This figure represents the difference between actual cases and the number that are diagnosed, investigated and from which isolates are serotyped and are captured by the FoodNet and PulseNet systems.

The 2010 outbreak

In July 2010, the CDC detected an increase in SE isolates with a common JEGX 01.004 PFGE pattern. Based on a 5-year baseline of approximately 1,400 cases over the period May 1 to October 15, the CDC estimated that there were in the region of 2,500 incident cases associated with the common source. Trace-back investigation determined that Wright County Eggs and an affiliate, Hillandale Farms of Iowa, were responsible for dissemination of SE.

On August 12, the FDA carried out field evaluation of Wright County Egg facilities and documented deviations from accepted management practices relating to hygiene and rodent control. Records confirmed the presence of flocks with environmental Salmonella enteritidis infection dating back to initiation of testing in 2007. The egg recall was announced on August 13. Reports of outbreaks dropped sharply in September through October.

The epidemic curve shown in the attached figure was consistent with factors that precipitated presumed high levels of transfer of Salmonella enteritidis to eggs, coupled with proliferation in the chain from production through to consumption.

It is hypothesized that factors which contribute to the 2010 outbreak involved either a failure in the FDA-mandated cold chain of 7C from collection through to purchase. Alternatively, some other factor, such as initiation of molt by starvation or other stress occurred which increased the level of vertical transmission through eggs to consumers.

Principles of Salmonella enteritidis prevention in the U.S.

Various measures have been taken to reduce the incidence rate of Salmonella enteritidis in consumers in the U.S.:

- By following the National Poultry Improvement Program Regulations, Salmonella enteritidis has been effectively eliminated from commercial breeding stock through to the parent stock and commercial hatchery levels.

- Structural and operational biosecurity is still deficient in the U.S. compared to the EU, but is undergoing improvement. This has been stimulated by the realization of the magnitude of losses associated with Salmonella enteritidis infection, especially in the light of increased surveillance and publicity.

- The U.S. egg Industry has adopted vaccination as a protective measure. Most producers now administer two doses of live mutant Salmonella typhimurium vaccine to pullets and are now using Salmonella enteritidis inactivated oil emulsion prior to transfer of flocks to laying farms.

- Surveillance has been increased. The most diligent producers conduct environmental assays at the time of delivery of chicks; 2 weeks prior to transfer; between 40 and 45 weeks of age; after initiation of the second cycle following molting and within two weeks of depletion.

- Surface contamination of eggs with Salmonella enteritidis is effectively controlled by washing eggs in a chlorine-based detergent-disinfectant solution.

- The FDA has mandated a cold chain with eggs held at 7C in off-line production units and during transport, continuing after packing through to the point of purchase.

- The USDA and the American Egg Board have implemented educational programs for both consumers and institutional kitchens relating to the safe handling and preparation of eggs and egg dishes.

Responses to the recall

The FDA has initiated inspections of U.S. farms and complexes to ensure compliance with the Final Rule. Although there has been a rapid restoration of selling price, confidence in shell eggs may be eroded by additional recalls, one of which occurred in early November. The increase in egg price during late October and early November is attributed more to depletion of up to 7 million hens identified as positive as a result of intensified Salmonella enteritidis surveillance than restoration of demand.

There will be an increase in consumption of pasteurized egg products, especially in commercial and institutional kitchens. If consumption of shell eggs does not increase, and as new hens are placed, lower prices will result in decreased returns especially for generic eggs. In-shell, pasteurized eggs will increase in popularity, especially for the elderly, and consumers with health problems which predispose to severe complications following Salmonella enteritidis.

It is possible that additional outbreaks of Salmonella enteritidis infection, especially if publicized, will result in cessation of production by some producers and will advance the rate of restructuring through acquisitions by more progressive companies with higher standards of disease control. The majority of existing in-line, multi-aged complexes in the US comprise “high-rise” housing with A-frame cages over manure pits. Because of the difficulty in controlling rodents and flies and persistence of infection, it is anticipated that many of these units will be retrofitted with on-belt manure batteries which are easier to manage, make use of the cube volume of the house and show a superior return on investment with a lower risk of Salmonella enteritidis infection compared to traditional housing.

Future opportunities

Enhanced trace-back will be required through the entire industry, involving both in-line and off-line production. Bar-coding will become the standard for positive identification of product through the entire chain, comprising production, processing, distribution and sale. More effective diagnostic techniques incorporating sensitivity and specificity are required.

Federal authorities will have to accept PCR technology, since results of environmental assays should be available within two days to determine the status of a flock or whether eggs are contaminated. The level of biosecurity on US farms will have to be enhanced with specific attention to hygiene of personnel, rodent control and monitoring the status of flocks. Immunization will have to be upgraded including the application of new and more effective vaccines with complementary methods to quantify serologic response.

The bottom line

The 2010 recall was a major shock to the U.S. generic shell-egg industry. Producers, either individually or through their associations, have demonstrated unjustified complacency and denial which has been shattered by the financial impact of the recall.

At the end of the day, it must be remembered that the problem was confined to 3-4 percent of the nation’s complement of 280 million hens. At least 90 percent of the industry functions according to currently acceptable practices, providing a nutritious and wholesome food product. It is probably not possible to eradicate Salmonella enteritidis, but a combination of good production practices at the farm, processing and distribution levels can minimize infection and reduce the relatively lower number of outbreaks attributed to eggs to less than 10 per year.