Modern hatchery operations require that incubated eggs hatch in a tight pattern of time, with a high percentage of chicks being hatched at around 492 hours, which is 12 hours prior to pulling flocks from the hatcher machine. Typically, hatcheries are able to achieve hatch rates of 55% to 65% in this window of time.

"In modern hatcheries, where man-hours are closely monitored, they don’t wait for chicks to hatch. The hatched eggs are pulled, and if the chicks aren’t ready, the window of opportunity is gone,” said Jeanna Wilson, associate professor of poultry science, University of Georgia.

Having as many eggs as possible hatch in a tight pattern means higher hatchability and healthier chicks, which are neither dehydrated because they hatched too early and stayed too long in the incubator, nor too wet, or “green,” having hatched too late and, therefore, being susceptible to becoming chilled in transport to the broiler farm.

High yielding strains present challenge

Eggs from high-yielding poultry strains, however, are presenting a challenge in managing the hatch window or pattern, Wilson said in a speech at the Hatchery-Breeder Clinic in Atlanta.

Because of the higher metabolic rate of higher-yielding breeds, the eggs produce more heat in the hatcher machines, which leads to more chicks hatching early.

Not only does the hatch pattern affect hatchery productivity and costs, it also affects chick quality and broiler mortality in the grow-out house, according to research reported by Wilson.

There have been sporadic reports of high 7-day mortality, Wilson said, anywhere from 3% to 8% after placement in the broiler house.

“Chick quality is what hatchery managers get hammered about more than anything else. When the chicks arrive on the broiler farm and there is higher mortality, hatchery managers hear about it,” she said.

Temperature most important factor

A number of factors influence incubation and the hatch window, but temperature is the most significant one. “Temperature is the most important factor or influence on when the egg is going to develop and hatch,” Wilson said.

Temperatures from 99.5 F to 99.8 F have been normal incubation temperatures in the broiler industry for many years.

Other influences on incubation include air velocity and penetration among the eggs and relative humidity.

“Some relative humidity is needed, but if there is too much it will cool the machines too much and interfere with temperature regulation,” she said.

Hatch window

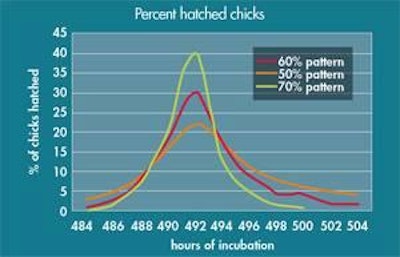

Wilson showed different theoretical hatch curves on a chart. “Achieving a hatch rate of 55% to 65% in the hatch window is what the industry has been shooting for,” she said. When the hatch is 50% the curve really widens out, she explained, and too many chicks are hatching early or late.

“The big issue in the last five or six years is that hatching eggs from the high-yielding strains are producing more heat. Their metabolic level is just higher, and they produce more heat in the incubators. So to prevent overheating, we must decrease the setter temperature. The big question that we’re all struggling with is how much to decrease the temperature,” she said.

Research study

Wilson described hatchery studies that she and fellow researchers had conducted with high-yielding strains. The following three hatcher temperatures were studied:

- Cool or 99.5 F

- Standard or 99.7 F, which is slightly cooler than the industry standard

- Hot, or simulated industry standard, of 100.3 F

Hatch rate. There was a lower hatch rate with the cool (82.3%) and the hot (83.3%) temperatures and a higher hatch rate (87.5%) with the standard temperature. “All of these hatch rates were in the acceptable range, but not as good as desired,” she said.

Hatch of fertile eggs. There was slightly depressed hatch rate for fertile eggs incubated in the cool temperature (89.8%) and a somewhat depressed hatch rate with the hot temperature (88.8%). These hatch rates compare to 91.5% for the fertile eggs incubated in the standard temperature.

Breakout analysis. Wilson reported that in the eggs incubated in the cool temperature, a sizable number, about 1.5%, were lost at live pip. Meantime, around 0.5% of the chicks were lost at live pip in the hot temperature. Eggs incubated at the standard temperature suffered the least losses at live pip.

Chick weights. The chick weights and the yolk-free chick weights from eggs incubated in the cooler temperature were lower. “The chicks from eggs incubated at the cool temperature had more yolk material both wet and dry, which means they are not utilizing all of the yolk that they have. That is responsible for them not growing as well,” Wilson said.

Broiler mortality. “Somewhat surprising was the higher mortality at 42 days for broilers incubated under hot conditions. The chicks from eggs incubated at the hot temperature had high, unacceptable mortality. This really proves that with the hot temperature we are losing broilers in the broiler house,” she said.

Conclusions

“Some of the weaker chicks from eggs incubated at the cool temperature were left in the shell. That is not the case with chicks from eggs incubated at the hot temperature, where those weaker chicks made it to the broiler house and died there. This shows the great impact of temperature, even slight variations in temperature,” she said.

“Higher yielding strains do benefit by lowering incubation temperature. But that magic temperature is likely strain specific, and I don’t think we’ve got it nailed down yet,” she concluded. “It is likely that some change in relative humidity is needed to raise hatchability as temperature decreases.”