In the past, it was the cow that received most attention over problems of lameness. But modern times have seen almost as much emphasis being given to the foot health of the pig.

Some of the reasons for this relatively new focus can be found in a combination of productivity and pens. An animal that is expected to grow faster or reproduce more abundantly must first be capable of standing and moving, yet there is a greater than ever drain on its body for resources of the nutrients needed. At the same time, housing conditions have become more demanding for movement and for the pig's ability to compete in a large group.

But the focus on feet and legs also owes something to an adjustment of herd records. Whereas previously the removal of a breeding sow was likely to be listed as due to poor reproductive performance, today there is a recognition that the real cause in many cases was poor feet.

Focus on the sow

Inevitably it is the foot health of the sow rather than the weaner or growing-finishing pig that has received most of the renewed interest. We want to limit the number of sows that are culled for failed locomotion so that more of these animals stay longer on the herd inventory. In any case, more foot problems are seen in mature breeding females than in their immature progeny.

Most of all, it seems, we should be looking at the sow in lactation. At an international veterinary gathering earlier this year, Dr John Deen of the University of Minnesota, USA, told us that no other animal beats the lactating sow for the amount of stress on its body as a function of its weight.

The lesson from this is that we should be analysing every sow at farrowing for evidence of foot troubles. Dr Deen advises producers to take a flashlight at night and check what they see of sow mobility in the semi-darkness of a farrowing pen. It is important to differentiate what you see, he added. Learn to distinguish whether or not sows are lame.

Realise, too, that you may be seeing a result of aggressive behaviour. Fights between sows more often tears up the feet than the shoulders, yet there is still a tendency to check first for shoulder wounds when inspecting sows for signs of fighting.

Begin with the claws

When inspecting the feet of an animal, according to Dr Deen, the stockman's eye usually goes first to her heel area. But the heel is not the part of the foot that bears the most weight. Begin instead with the claws and the area of tissue above them.

A starting point here would be to look for a common fault that is known either as a sand crack or as a white-line wall crack. The attendant could use a conventional scoring technique to record what was seen, such as one that allocated a simple 0-1-2-3 score to register absence or presence and severity. However, Dr Deen commented to us that even this might be too much. In reality, he said, any lesion detected is likely to be either small or extremely significant. So we probably do not need a scoring system that goes beyond 0-1-2.

What does it mean? Just as in the dairy herd, the primary emphasis needs to be on animal comfort. At an extreme, a lame sow may need to be euthanised. Also, consider that cracked claws at farrowing time will mend only slowly — at a rate of regeneration of 7 millimetres per month. It could be 4-5 months before tissue turnover is complete. During the lactation period, lameness must be at least suspected of potentially interfering with the sow's daily feed intake so she does not produce enough milk to suckle her litter adequately.

What is more, poor feet may point to faulty flooring. Most farrowing floors are evaluated for factors such as drainage, not for standing behaviour, and the standard evaluation assumes a healthy animal. Herd lameness scores have their greatest value in an aspect like this, by giving the first clue to trends that might be correctable by a change in management or facilities.

More generally, any attempt at allocating a score to feet for the appearance of faults would be a waste of time unless it was used in combination with the recording of the sow's breeding performance. The same would be true of any measurement of welfare — it needs to accompany the normal record of productivity so future observations can be linked to forecasts of the effect on herd output.

Says Dr Deen, "I tell farmers they cull sows for such reasons as returning to oestrus or having small litters or savaging the piglets, but I have never seen anything else like this in the herd that can predict the success of the sow in terms of her future productivity."

More progress has been made so far in reacting to sows' foot troubles than in preventing them. But there are suggestions that it is possible to improve the foot health of the breeding sow by paying extra attention to her feed.

Positive signs that this is indeed a possibility have come, for example, from Danish trial work reported this year by Hans Aae of Vitfoss in Denmark. At the 2008 FeetFirst symposium arranged in the USA by Zinpro Performance Minerals, he described results from supplementing the feed of gestating sows with organically bound trace minerals. The comparison was with feed mixtures in which the mineral supplements providing copper, zinc and manganese were in an inorganic form.

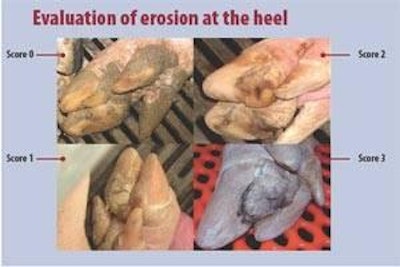

It was done in a herd where sows at farrowing time showed problems of claw cracks and erosion of the heel. Evaluations that continued for two years after the change in mineral sources found that while problems of heel erosion affected 80% of lactating sows fed the inorganic minerals, this fell to only 30% in the organic minerals group. Only a few claw cracks were observed in both groups.

A year ago, follow-up work at another Danish unit demonstrated another effect associated with the mineral changeover. This involved a herd of 1,000 sows in which losses averaging 20 sows per month were occurring due to culling or euthanasia and half of those were estimated to be due to leg or feet problems. Sow deaths dropped to 50% of the starting level within about two months of switching the minerals to organic versions that were reckoned to be more available to the animal.