Where scanning is concerned, not much has changed on farm since the doppler and A scan ultrasound machines began to be used for routine pregnancy diagnosis during the 1970’s in Europe.

However, unlike these early devices, the modern versions now provide a good ultrasound image based on a procedure termed ultrasonography, which provides useful and potentially valuable information.

These sophisticated devices allow us to see inside sows, gilts and now, even the scrotums of our breeding boars. This increases the potential value of their use, both for routine tasks and in the hands of a skilled specialist operator.

Despite this, ultrasonography in pigs still seems to be a rather “European” practice. It is not clear why this should be the case, but it is almost certainly to do with production costs being higher in Europe than elsewhere. However, with the recent worldwide increase in feed and energy production costs in particular, technologies that help to reduce input costs might become more attractive.

How does ultrasonography reduce costs? It is principally because it helps to reduce non-productive days, and this is what it does regardless of the purpose it is used for.

A well understood example

Even though recent studies indicate that pregnancy can be seen as early as day nine in individual sows, when it comes to scanning on farms, a good recommendation is to scan animals between days 20 and 21 post breeding, which gives accurate results and is the period when non-pregnant sows are expected to return.

Since not every sow exhibits obvious signs of oestrus (heat), ultrasonographic diagnosis helps to unambiguously detect potential returners, providing the opportunity to monitor them closely and to maximise boar influence. Moreover, since ultrasonography also allows for visualization of the ovaries, it may also help in predicting the time when animals return and on the optimum time for insemination.

Ultrasonography is more reliable than any other methods used for pregnancy checking. What that means financially is easily calculated based on the following equations: Detecting a sow as being non-pregnant on day 21 rather than day 28 would provide the opportunity to rebreed or cull her seven days earlier. Given that the costs for an empty sow day are about Euro 4, it would mean savings of at least Euro 28. However, successfully detecting and impregnating a sow or gilt on its first return would save potentially 21 empty days and this would be worth around Euro 84.

Checking for puberty

Ultrasonic devices have the potential to save money in a variety of ways and a good example is checking for puberty.

Across the pig industry, there are always significant numbers of gilts culled for not exhibiting oestrus. These gilts usually require increased attention, which is costly and may not be successful. Occasionally, heat detection procedures are poor. In other situations gilts truly do not cycle.

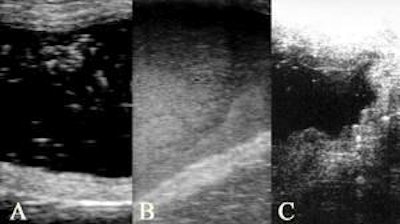

Whatever the reasons, ultrasonography enables accurate diagnosis of gilts as mature or not. This is based on the ovarian and uterine findings. With respect to the latter, immature gilts have a relatively tiny uterus, clearly delineated by its small circumference. Not only does ultrasonography help to evaluate heat detection procedure; it also may give producers an understanding of when puberty occurs in their herds.

At the individual gilt level, a diagnosis is obtained that allows for a substantiated treatment. For instance, PG600 is only then appropriate if animals are immature and have ovaries with small follicles, whilst treatment with Lutalyse (i.e. PGF2 alpha) only makes sense if corpora lutea (yellow bodies) are present, clearly indicating that the gilt has already had at least one heat and is cycling. Both the follicles and corpora lutea can be clearly seen by ultrasonography.

Monitoring ovulation

Another use of ultrasonography is monitoring ovulation. In general, the reason for doing this is to evaluate breeding management, particularly the timing of service/AI.

It is well known that sperm need to be in the uterus for many hours before the eggs are released from the follicles (ovulation). Ultrasonography is the only non-invasive procedure that permits ovulation monitoring in the live animal on farm.

The size and shape of the follicles give good estimation of when ovulation may occur. Overall, the so-called peri-ovulatory period can be monitored in pigs. Again, this makes ultrasonography a very valuable tool.

In other situations, when changes have been made to management with potential impact on herd fertility, such as the use of new breeds, introduction of hormone treatments, or changes to the timing of service, monitoring ovulation using ultrasonography is a perfect procedure to accompany those changes and make necessary adjustments. Finally, the value of monitoring ovulation for troubleshooting should not be forgotten.

Diagnosis of reproductive failure

A further reason for ultrasonography is for the diagnosis of reproductive failure. This can be an individual sow problem or a herd issue. For instance, animals that were found empty during a pregnancy check may be scanned more closely to determine whether they have, for instance, an inflamed uterus or ovarian failure. Moderate to severe cases of uterine inflammation can be detected, as can various forms of cystic ovarian degeneration.

Equally important, ultrasonography can be used more strategically if there is a herd problem that requires a comprehensive troubleshooting approach. In cases of low conception or farrowing rates, it is logical to begin the diagnostic procedure of monitoring ovulation to determine when animals ovulate relative to time of breeding. If this is not a problem, then you may check very early after breeding to see if there is embryonic loss. Based on the ultrasonographic findings, recommendations can be made for additional diagnostic procedures.

Diseases of the bladder

Ultrasonography can be used to diagnose some bladder diseases. This is all the more important as there is a close relationship between bladder disease and genital infections. More specifically, sediment (e.g. in the bladder urine) can be clearly seen by ultrasonography and can also be quantified on a score system.

Male reproductive tract

Ultrasonography has proven to be suitable for examining the male reproductive tract. This would not be a procedure on a herd level, but part of an individual soundness for breeding examination. The testes, epidydimides and accessory glands have been described visually by ultrasonography; thus it is suggested that this technique is helpful in cases of individual boar infertility. More recently, it has also been shown that there is an association between some semen parameters and epidydimal echogenicity.

.jpg?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=crop&h=167&q=70&w=250)