If there is no action today, there will be no cure tomorrow. This was one of the messages to attendees at a conference on antibiotic resistance, held in Bangkok, Thailand, in March, which looked at various ways of tackling resistant bacteria, from restricting access to medicines to reducing poultry stocking densities.

Delegates were warned that bacteria resistance to the newest anti-infectives have been detected, and the question was raised as to whether there may be strains already in circulation that could be resistant to any future antibiotics. This would be of particular concern in the case of poultry health as there are so few antibiotics suitable for use in poultry currently under development.

The problem of antibiotic resistance is a global, cross-species (including human) and cross-discipline issue, and all sectors need to play their part. The issue of how to reduce the spread of resistance is further complicated by the fact that rules and regulations differ from region to region and country to country, as do livestock production methods.

In Asia, for example, it was said that biosecurity is weaker than in many other parts of the world, and that given the proximity of one poultry production site to another, disease would easily spread without the use of antibiotics if current methods persist and no proven alternatives are employed.

It was emphasized that while only 20 percent of antibiotic resistance is thought to have originated from agricultural use, this is a problem that will not go away. Once resistant strains emerge, they are here for good. We all need to play a part in halting their spread.

How did we get here?

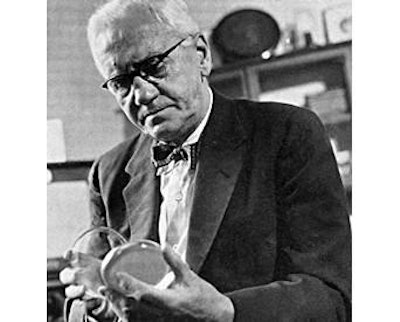

Fears over antibiotic resistance are not new. Sir Alexander Fleming, credited with discovering penicillin in 1928, was awarded a Nobel Prize for his work in 1945, at which point he raised the alarm over the possibilities of resistance.

Resistance began to emerge in the 1960s, and in late 1969, the UK government published the Swann Report. It concluded that: "The administration of antibiotics to farm livestock, particularly at sub-therapeutic levels, poses certain hazards to human and animal health." In particular, it had led to resistance in enteric bacteria of animal origin, the report stated.

This resistance was transmissible to other bacteria and man. It had been the discovery that this might be so, followed by an epidemic of resistant S. typhimurium in 1963-65, which prompted UK ministers to appoint the report's committee.

The report recommended that only antibiotics which "have little or no application as therapeutic agents in man or animals and will not impair the efficiency of a prescribed therapeutic drug or drugs through the development of resistant strains or organisms" should be usable for growth promotion.

Routes of resistance

As we know, however, the problem has not gone away. Dr. James Campbell, microbiologist at the Oxford University Clinical Research Unit, UK, noted that as part of his work in Vietnam, he has found that it is common practice for families to keep antibiotics in the home medicine cabinet. He also reminded delegates that in many cultures, a patient visiting a general practitioner will not be happy unless given a tablet – irrespective of its appropriateness for the condition – and that a similar story often plays out on farm.

He noted that visits to chicken farms in Vietnam have found massive loads of resistant bacteria, and that these bacteria were also present on poultry farmers. However, the problem is not restricted to the farm, and rats have also been found with high levels of resistant bacteria. It is thought that rat contamination occurred, via duck or pig farms.

Of additional concern, he noted, was that in Asia, some 50 percent of drugs are fake or substandard.

Farm management lessons from public health

Dr. Wim de Wit, from the Dutch Ministry of Agriculture, warned that there are now people suffering or dying because some antibiotics are no longer working due to pathogen resistance.

In the absence of functioning antibiotics, alternative approaches to protecting health, be it human or animal, must be found.

Looking at Europe, he showed a downward curve in the human mortality rate in the Netherlands throughout the 20th century. This resulted from improved hygiene, and he went on to say that improved management could help reduce disease and slow resistance development at farm level.

He gave the additional example of 2003 data from a monitoring program in the Netherlands. It showed a correlation between poultry culled as a result of avian influenza and a reduction in levels of antibiotic-resistant bacteria detected in humans.

"The system is overloaded." he said. "One of the possibilities [to address this] is to limit the density of farm animals."

However, in an era of global trade and global travel, the efforts of one country acting alone will have little impact.

"It is no use if only the Netherlands, which is a small place, is working very hard on it and others don't," he said. "The feed and food producers, the farmers, the vets, the retailers, the consumers – the whole production chain is responsible."

That there needs to be a coordinated approach was demonstrated by the revelation that there are more resistant strains of bacteria in Southern Europe than in Northern because of ease of access to medicines, while in India, there is now a totally resistant strain of tuberculosis.

He warned, "This could be the end of modern medicine as we know it."

Multiple risks

As resistance has spread, so its impact and mode of spread have increased, as have the possible risks for human health. For example, delegates were told that 13 percent of human urinary tract infections are due to a bacterium that is found in poultry. There is an increase in the levels of antibiotic-resistant bacteria found in soils, while in Portugal, seagulls spreading "superbugs" have been reported. U.S. reports suggest that there is abundant antibiotic resistance on Chinese pig farms.

With food now sourced from and traveling all over the world, resistant bacteria are traveling with it. So the rise of antibiotic resistance not only poses a threat to food safety but also to food security. It is not simply something happening in some far-off distant land.

Various proposals were preferred as to how the problem could be tackled on farm and how this could be encouraged by various stakeholders.

For example, it was suggested that:

- Farmers not only practice better hygiene, but also use lower stocking densities; feed should be high, and there should be an exclusive relationship with the vet, preventing farmers from sourcing medicines elsewhere, and allowing the veterinarian to maintain proper controls

- In the case of poultry in particular, it was suggested that birds be kept for a longer period – 40-45 days – allowing them to develop better immune responses

- It was also suggested that the approach of prevention being better than cure be discussed at a global level

- The FAO could issue guidelines

- Greater use of bacteriophage (a bacteriophage for Listeria is already marketed, while one for Salmonella is being tested)

- Prebiotics, probiotics, acidifiers and plant extracts were also examined, however, they are not suitable across all production systems and in all circumstances

These approaches, either alone or in combination, offer ways of slowing the growth in resistance. Everyone, particularly those at the top, need to be more aware of how bacteria are winning in their struggle for life.