The overall state of health of layers and pullets in the U.S. is good at the present time. But Dr. Bernie Beckman, director of technical services, Hy-Line North America LLC, identified seven active diseases or syndromes in layers and pullets in the U.S.: focal duodenal necrosis (FDN), bone diseases, Mycoplasma gallisepticum (MG), infectious bronchitis (IB), fowlpox, infectious laryngotracheitis (ILT) and E. coli peritonitis.

Beckman, who spoke at the Midwest Poultry Federation Convention's Pullet and Layer Health Workshop, said, "FDN is probably one of my most challenging diseases. Is it the most critical to the layer industry? I'll leave the determination up to you and your own farms. For me it is one of the most challenging because there isn't a clear diagnosis for this disease."

FDN hard to diagnose

FDN is an intestinal disease syndrome of pullets and layers which has been recognized in the U.S. for at least 15 years and has also been found in Europe. Beckman said that FDN causes necrotic lesions or spots on the wall of the small intestine in the duodenum, just down from the crop.

"You can't find these lesions in dead birds; you have to sacrifice live birds to find it on necropsy," he said.

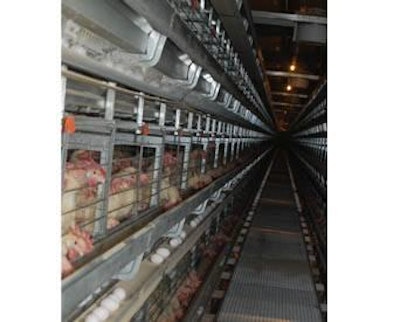

Beckman said FDN can be found in all genetic strains of layers, both brown and white. FDN has been found in flocks raised in every type of management system: cage, cage-free and even organic flocks. It has been found in pullets as young as 14 weeks of age and has been found in layers at all stages of production. He said that the only "observable" clinical sign in affected birds is that they tend to have pale combs.

Beckman said that FDN can be commonly found on U.S. layer complexes. In a study of spent layer flocks conducted nearly 14 years ago, he said 39 percent of the flocks were found to be positive for FDN upon necropsy. FDN is hard to diagnose in the pullet house and is usually only recognized in the layer house when a flock is slow to achieve desired egg weights. The reduced egg size is the most common manifestation of the disease, according to Beckman, although he said some flocks can also experience as much as a 10 percent drop in the number of eggs produced. The most common time to recognize FDN is as the flock approaches peak and the flock is unable to reach standard egg weights. FDN doesn't increase flock mortality.

FDN's cause uncertain

There is no proven cause of FDN, according to Beckman, although it is closely associated with Clostridium infection. In this way, FDN is somewhat like necrotic enteritis in broilers. He said that researchers at Auburn University were able to isolate bacteria that were gram variable, slow growing, long filamentous anaerobes. He said evidence to date suggests that Clostridium perfringens and/or Clostridium colinum are involved in the syndrome. Most antibiotics that are effective against gram-positive bacteria will efficiently treat FDN.

FDN has been seen in flocks with or without tapeworms. It isn't associated mycotoxins or biogenic amines in the feed. To date, no viruses or spirochetes have been isolated that are associated with FDN. Beckman said FDN may or may not be associated with coccidiosis problems.

Economic impact and treatment

The biggest cost of FDN is the loss of revenue due to lowered egg weights. Beckman said egg weights can be reduced by as much as 2.5 grams per egg or 2.0 pounds per case. In addition to this, egg numbers can also be reduced below standard, sometimes by as much as 10 percent.

Bacitracin methylene disalicylate (BMD) "is the first, second and third option for treating FDN," Beckman said. The recommended treatment is 25 grams of BMD per ton added to the feed for four weeks, or longer if needed. He said treatment usually is started when egg weights are affected or production is very poor. He said chlortetracycline and penicillin have worked well in the past for treating FDN, but that BMD is the only treatment option available now. Alternative products such as organic acids and probiotics are being explored as possible preventatives or treatments for FDN.

Beckman said cleaning and disinfecting the layer and pullet houses between flocks was not effective in reducing the incidence of FDN in subsequent flocks. FDN can also recur in the same flock after treatment with BMD. Beckman expressed some concern that the low-BMD-dose treatment that he described for FDN might be considered subtherapeutic treatment based on new FDA drug use guidelines. He questioned whether industry will be able to keep feeding at low doses in the future, particularly if the BMD is fed as an FDN preventative. He suggested that the layer industry will need to pay more attention to gut health in the future, because of the limited availability of non-withdrawal antibiotics and the new veterinary feed directive.

Bone diseases in layers

Osteoporosis and osteomalacia are two syndromes which affect the bones of layers. Osteoporosis tends to affect older hens, and it results in bones with normal mineralization but reduced mass. Osteomalacia can occur in layers of any age and it results in bones of normal thickness, but they are soft and pliable, because they have normal mass but reduced mineralization.

Beckman said osteomalacia is the bigger problem in U.S. layer flocks. He said keel fractures and deformities are the primary signs of osteomalacia, and these are associated with "crash landings" or chronic pressure points in enriched colony cages or aviary systems. Because hens strip minerals out of their bones to make good eggshells, Beckman said it is possible for a flock with soft bones to have good eggshell strength. He said that feeding calcium to the flock early is one way to address this problem, but starting too early can lead to the flock developing urolithiasis, or kidney stones.

Beckman recommended changing from a 1.4 percent calcium developer ration to a 2.5 percent calcium pre-lay ration when the hens' combs start "blooming." He also said that the pre-lay rations should be used for 1-2 weeks before egg production starts. The transition from the pre-lay ration to the 4-5 percent calcium layer ration should take place at first egg or no later than when the flock is at 0.5-1.0 percent production per day, according to Beckman.

If you have a flock in the layer house with soft bones, Beckman recommended adding 35 pounds of large particle limestone, 20 pounds of dicalcium phosphate, and 1 million units of vitamin D3 per ton of feed for two weeks. He said this treatment will increase the calcium and phosphorous concentrations of the feed by 0.9 and 0.185 percent, respectively.

Mycoplasma gallisepticum

The biggest clinical sign that a flock is infected with Mycoplasma gallisepticum (MG) is usually a drop in egg production. The hens can sometimes exhibit signs of a respiratory problem, but many times there are few respiratory signs. Beckman said MG is generally a silent disease in adult layers, but there may be a mild respiratory noise. MG can interact with viral diseases or even vaccines to produce severe chronic respiratory disease. MG has been known to cause soft egg shells or pimpling of the egg shells. Wild strains of MG can break through and infect vaccinated flocks.

Diagnosis of MG via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is becoming more common, Beckman reported. He said PCR allows for the specific strain of MG to be identified. Several biologics companies offer MG vaccines and that many are used in combination with Newcastle and bronchitis vaccines.

IB, fowlpox and ILT

Beckman identified three viral respiratory diseases of chickens that are challenging the U.S. layer industry to a certain degree: infectious bronchitis (IB), fowlpox and infectious laryngotracheitis (ILT). Vaccines are available and commonly used for each of these diseases, but the diseases continue to be somewhat of a problem for the industry.

"IB continues to be one of the most important diseases, causing losses in egg production as well as shell and internal egg quality," Beckman said. Rough egg shells and poor interior egg quality, "runny eggs," are common symptoms of IB infection.

Seasonal outbreaks of ILT continue to occur in some areas of the country, Beckman reported, and "wet pox" and "dry pox" outbreaks continue to occur in vaccinated flocks at a low incidence. Vaccination programs are available to control the spread of ILT and protect flocks in outbreak areas. Beckman also said a combination of pigeon and fowlpox can be used in areas having trouble with fowlpox break.

E. coli peritonitis on the decline

Peritonitis caused by E. coli is less common in layers than it has been in the past, according to Beckman. He suggested a number of possible reasons for the decline in incidence of this disease:

- More cage space with various welfare requirements

- Better air quality, such as less dust and ammonia

- Less stress

- Common use of E. coli vaccination

Beckman said that the additional cage space provided to hens, better air quality and the E. coli vaccine have all contributed to the reduction in peritonitis in layers. He said that peritonitis may pop back up in housing systems with litter floors because of increased dust and ammonia relative to what is found in cage systems.

Diseases to watch for

Marek's disease, inflammatory bowel disease, coryza, spirochaetes, coccidiosis, Salmonella enteriditis and gout are all diseases that Beckman said are under control but that need to be closely monitored. He said egg producers must be vigilant about biosecurity because there are highly virulent strains of disease organisms that can come into our country and wreak havoc. He cited the current problem that U.S. swine producers are having stopping the spread of porcine epidemic diarrhea (PED) virus as a warning for U.S. egg producers. The layer and swine industries house animals on multi-age farms which are not routinely depopulated, and this makes biosecurity extremely important for swine and egg producers.