In a previous article, we defined the concept of nano management as the real-time management of issues that can affect the quality, safety and yield of processed chickens. In that article, we also emphasized the need to remain vigilant for "hidden costs."

It is common practice for poultry companies to ensure that the various operations along the processing line are conducted properly, and many plant managers or owners use monitors or screens relaying data from strategic points along the processing line. Data may include:

- Hanging on the shackles: Are all shackles full? Has the processing speed been established?

- Exit from the pluckers: Have all chickens been properly plucked?

- Evisceration: An overall view showing section personnel at work

- Chiller output: Revealing whether chickens coming out of the chiller are hanging on the drip line

- Cold rooms: To see whether crated/boxed birds are entering the coolers without problems

- Dispatch: Are trucks being loaded on time to ship clients' orders?

We also noted that one of the great challenges that processing plant managers face is to ensure, with their teams and simple tools, the successful operation of the plant.

If we look at successes in maximizing efficiency in vehicle production, there are two basic monitoring approaches: Muda, or total waste control, and Gemba, or real place.

These management models can also be successfully applied to poultry processing plants.

Muda

The seven classes of waste in operational processes were defined by Taiichi Ohno, who designed the Toyota production system. Similarly, classes of waste can be identified along the final part of the broiler production process, for example, at pre-slaughter, catching, transportation, in waiting time, during processing, through overproduction, reprocessing, and storage.

Over time, the original "waste list" has been updated and revised in response to changed circumstances, and these changes also are visible in the poultry business:

- Time wasted due to unnecessary delays, often due to a poorly planned work rota;

- Unnecessary movement, in many cases the result of a poorly designed processing plant;

- Unergonomic working conditions and methods; consequently, staff do not perform well without additional effort;

- Efficient production of the wrong product; if what is produced is not what is needed, cold room inventory will increase, and energy and maintenance costs will rise. This has an impact on the cost per kilo of processed chicken;

- Failure to close the circle, for example, if time saved in one area is not put to good use in another, there is no effective saving;

- Wasted knowledge and human resources; without the right organizational structure to continually stimulate creativity for new products and improvements in existing products, valuable talent is wasted;

- Failure to recognize human potential; studies have shown that the failure to address this small but significant detail can make all the difference between success and failure.

Gemba

This Japanese term means that in order to successfully monitor in real time, those responsible for the task must be physically present, so that they can observe, evaluate and take corrective action as quickly as possible.

This workplace management concept can also be applied to poultry processing to improve the competitiveness of the company.

Before Gemba can be put into practice, however, "Control Circles" need to be established. The Control Circles are the points along the processing line where, on a daily basis, monitoring must take place and comprise:

- The stunner - input and/or output

- The final plucker - exit

- Eviscerated carcasses prior to entering the chiller

- Giblet processing

- Chilling - pre-chiller and chiller

But why are these specific points so important?

The stunner

By monitoring the birds entering the stunner, any pre-shock problems can be identified and remedied. Problems at this point can have serious implications for the automatic slaughter of the bird and carcass quality. If birds are leaving the stunner still conscious with a raised or shrunken neck, they will not pass through the machine guides to be slaughtered.

At the stunner exit, the success of the operation can be evaluated. Birds must be unconscious, have dilated pupils, a slight curve to the neck, their wings held close to the body and be totally calm.

Exit from the final plucker

On exit from the plucker, wing veins should be dilated, and there should be a widening of the vein near the thigh joint, which should have a bluish tinge.

Wing tips should not have accumulated blood and there must be no tonality. Any trauma pre-slaughter will present as hematomas, which are dark in color.

Chickens should be completely free from feathers and the skin should be intact. There should be no scratches or breaks to the skin, particularly around the wings, where the humerus may emerge.

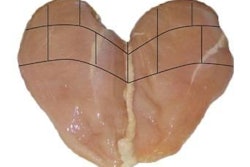

As a check, make a statistically established selection of birds and cut the skin to examine the breast. This should show the natural color of muscle and subcutaneous fat should be attached to the skin.

Eviscerated carcasses prior to chiller entry

It is worth keeping in mind that, at this control point, the dry carcass yield, including the neck but without the head, should be a minimum of 76 percent. In some plants it can be as high as 78 percent. At this point, it is worth reviewing the following:

- Is the abdominal fat intact? It should weigh some 40 grams.

- Is the neck cut of sufficient length?

- Is the head cut flush with the first vertebra?

Giblet processing

Irrespective of the automatic evisceration system used in the processing plant, the handling of the intestinal package, from the moment it is separated and removed from the chicken, should be monitored with a focus on the following:

- With regard to processing the gizzard, does the automatic system cut, wash, clean and completely remove the cuticle?

- Is the percentage of lost meat known? Sampling should be carried out.

- What percentage needs to be reprocessed to completely remove the cuticle?

- Chilling: pre-chiller and chiller

- At the pre-chilling and chilling stages of poultry processing, particular attention needs to be paid to the following;

- Are chicken carcasses completely and uniformly submerged?

- Is there foam - subcutaneous fat - on the water? Visually estimate how much foam may be present. It there too little, is the amount about right, or is there too much?

To sum up, following the Gemba philosophy will keep the various operations performed during the processing of chickens thoroughly under control.