There are several phases during harvesting and processing where broilers are likely to flap their wings and potentially affect the quality of the final processed carcass. Paying particular attention during these operations, however, can help to maximize the volumes of Grade A processed chicken.

Harvesting

Broilers will react to the behavior of the harvesting team. Birds tend to move around the poultry house slowly, and so the catching team should do so in the same way.

A failure to do so will result in birds panicking and rushing toward the side walls. This panic sees them take short flights and jump on top of each other. This may not only result in scratching but also suffocation and death.

When birds take these short flights, the large pectoral muscle responsible for moving the wings is stressed more than the minor, given that the latter is not fully extended. This exerts pressure on the blood vessels and they may break, with the escaping blood resulting in a bruise.

Some veins may simply be weakened. The impact of this on breast meat quality may not be immediately apparent, however, this weakening of the vessels may have consequences during processing.

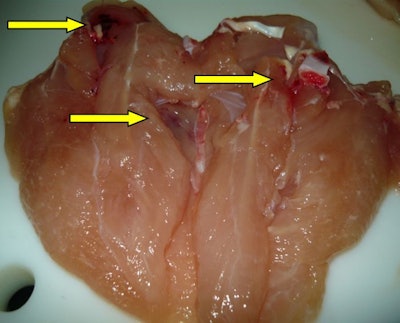

When birds are stunned, some of the weakened blood vessels will burst, in the same way that some of the fragile bones in the thorax may also break. When this occurs immediately prior to slaughter, any bleed will retain a bright red color.

If birds are crowded together and flap their wings, damage can occur externally and internally, particularly where the humerus meets the ulna and radius, and these repeated impacts can result in bruising.

Caging

The wings are the most delicate part of the broiler’s body. This is why chickens should not be caught by the legs -- allowing the wings to flap -- but by the body, with the wings pressed gently to the abdomen.

This same care needs to be demonstrated when placing birds into cages or other containers for transport, without compromising speed of operation.

In some companies, metal cages with various levels are still used. Wear and tear can result in the cage bars bending, loosening, or coming away altogether. This may allow birds to poke their heads or wings through any resultant gaps and these may become trapped during handling or loading onto trucks.

Should poorly maintained containers of this type be in use, they should be covered with a plastic mesh, with holes of an adequate size to still permit good air circulation.

Similarly, where cages are used, they should have lids. It is worth remembering that as soon as a broiler is caged, it will want to escape. In raising its head out of the cage at the moment that another cage is placed on top, the risk increases of fracturing a bird’s skull. In the best case, the bird will die instantly, in the worst, it will bleed to death en route to the processing plant.

At the plant

The move toward processing larger birds, in excess of 3 kg, presents new challenges where wing flapping is concerned.

Traditionally, the distance between the shackles on the overhead conveyor has been 6 inches, for birds weighing less than 2.5 kg. With this much space between smaller birds, they can be moved comfortably and do not flap, given that their breasts are in constant contact with the breast comforter, and assuming that everything else is as it should be.

However, this is not the case when birds weighing 3.5-3.8 kg are hung. Quite simply, they will not fit comfortably into the space provided, and consequently they flap their wings continuously on the way to being stunned. In some plants, the solution is to increase the voltage in the stunning bath. When this situation arises, wings may be damaged and there can be an accumulation of blood that is not fully drained during bleed out.

This will be evidenced at the exit from the last plucker where it will be possible to see blood vessels that are still full of blood, affecting the appearance of carcasses, and raising the number of rejects.

Due to the above, some plants have increased the distance between the hanging shackles to 8 inches. This would appear to be successful and has no negative impact when processing smaller birds.

Exit from the stunner

When birds are stunned successfully, they will leave the stunning bath shaking, the tonic phase. If birds are big and there is insufficient space between each one, they can knock against each other. This can result in significant damage to the wings.

If broilers do not relax enough prior to entering the guides leading to the automatic killer, during the clonic phase, they may rise above these guides, adding to the work of those responsible for ensuring that all birds are killed.

Additionally, depending on the type of guides used, when birds flap their wings during this stage, they will come into contact with the stainless steel equipment, and again may be damaged. Installing a plastic tube running along the route to the automatic killer can help to reduce any impact on the wings at this stage.

Installing plastic tubing along the approach to the automatic killer can help to reduce wing damage. | Eduardo Cervantes López

Poultry processing requires mix of expertise, automation