Breeding companies have their own views on feeding broiler breeder males and on the optimum mature weight guidelines to achieve high fertility throughout the life of the flock.

Emphasis in breeding program selection continues to be placed on improved feed conversion. Yet farmers often find this challenging as the male response to feed intake may be different. They can become too heavy, with negative effects on hatchability and chick production. This, however, does not need to be the case.

Focusing on the practical feeding of males during the production phase, with the adoption of a ‘rule of thumb’ method, can be successfully used to maintain top hatchability with large males.

The big question that most farm managers face is how much to feed.

Differences in frame size and weight within a population at transfer age make it challenging to feed the males. Research papers indicate that the parent male requires about 81-95 kcal of energy per kg of body weight. I work on 90 kcal/kg. We can now calculate accurately how to feed males, especially populations that deviate from the target weight line.

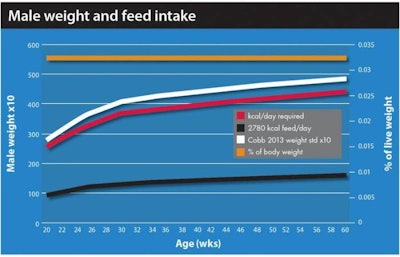

This method indicates that there is a ratio of feed to body weight. Graph 1 illustrates that the male energy requirement is in proportion to its weight, but as a percentage of weight, the feed requirement remains constant at 3.2 percent.

When considering how much to feed, the following factors need to be considered:

- Age

- Frame size, height, weight and breast muscle development (condition)

- House temperature

It is important that the male continues to grow moderately after maturing (30 weeks). The ideal weight gain is about 26 g per week from around 31 weeks through to 60 weeks. The problem flocks are those that are heavy at 30 weeks and then restricted to get the weight "under control."

Proper interpretation

When analyzing the male weight, it is not always clear that growth is the problem. Incorrect weighing and poor male uniformity can make it difficult. However, when the average weight is expressed as a percentage of the target weight, then it becomes clearer that, for example, heavy males at 30 weeks of age have "lost" condition and moved closer to the target weight over a long time. It must be remembered that individual birds would be affected differently, and therefore a drop in fertility is experienced.

The bottom 25 percent of males for hatchability in the above case study were 7 percent above the target weight, but were fed 10 percent less than the recommended feed intake of males on target weight. So why then do farmers feed bigger males less feed when their energy requirement is increased due to their size?

In this case study, we found that the top male flocks for hatchability were close to the target weight while they were fed about 10 percent more feed than the recommended levels.

So why did they not gain weight? The

answer is in the high levels of activity that help spend the energy consumed.

This is the key: Well-fed males will be more active and "burn" the energy while

big males that are underfed will become lethargic and use the feed to put on

more weight.

Very feed-efficient males (grandparent

males) were fed 2.8 percent of their live weight (grams) per day. Males with

less feed efficiency can be fed up to 4.2 percent of their weight in feed. Parent stock males are generally around 3.0-3.2%

of the live weight. When this method is

combined with the breast muscle scoring, large males can still hatch acceptably.

A male weighing 4.5 kg requires about

6-8 g more feed than a male of 4.0 kg, no matter what the age is.

In Graph 4, the male weights were 5 percent above target while the feed level was lower in the early stages and, through a too-slow feed increase after 45 weeks of age, the males started losing condition. The data of these top flocks indicated a low early hatchability that could be related to the low feed intake at this age.

Successful management

The successful management of males can be broken down into simple points. The most important tips are:

• Male feeding can be accurately calculated

• Males cannot be fed less than 128 g (357 kcal) and have good fertility

• Male feed must be increased over time as they get bigger

• Increasing feed when fertility first declines could restore the fertility (+5 g)

• Do not double feed in transfer week - it leads to unnecessary weight gain

• Ensure that young males are not underfed for optimal reproductive development

• Top flocks have better weight control and never exceed the weight target by more than 2-5%

• Top flocks gained 26-27 g weekly; more (30 g) or less (24 g) gain ended up in the bottom flocks

Modern males require precision management for best results and all farmers are capable of doing this with a weighing scale and good observations.