Good poultry farm biosecurity is a mammoth task, said Anthony Pearson, global technical consultant with Antec International Ltd., a company of the Lanxess Group, presenting at the webinar, "How to properly implement poultry farm biosecurity plans," presented by WATT Global Media.

Anthony Pearson said biosecurity needs far greater consideration given that producers now find themselves in markedly different circumstances compared with only a few decades ago.

Producers now find themselves in markedly different circumstances compared with only a few decades ago, he continued, and biosecurity planning and operations must take account of this.

Disease challenges are no longer restricted to the cooler months, necessitating a 365-day-a-year biosecurity focus. Restrictions on antibiotics use are tighter and, alongside these factors, demands for animal welfare are greater, which can complicate biosecurity controls.

Vaccination and medication were once sufficient to keep birds healthy. But now, while vaccination remains a key insurance policy and medication is necessary, biosecurity needs far greater consideration.

The more invested producers are in biosecurity the better the return, if not at least through reduced medication costs. This demands commitment and teamwork, good farm management, transparency and cooperation with veterinarians.

Proper consideration needs to be given to what is to be achieved through farm biosecurity and a plan drawn up, covering areas including rodent control, wild bird proofing and insect control. Regardless of what type of farm is being managed, plans must cover all inputs and outputs, looking at hazard analysis and critical control points (HACCP).

With the plan drawn up and HACCP examined, there is value in arranging an external audit, as a fresh pair of eyes will see issues possibly missed by those on-farm on a day-to-day basis.

Starting as you mean to go on

A good way to judge whether a biosecurity plan is working in the absence of any obvious issues is to look at the seven-day weight of broilers. The various genetics suppliers have guides giving anticipated 7-to-10-day weights.

Hygiene can really influence the starter period, and it is this time that really counts in broiler growth as whatever a bird does not gain during the first week cannot be made up for later.

While there are various tools available to protect flock health, none of these can break the chain of disease transmission from one production cycle to the next.

Should a challenge -- Salmonella, Campylobacter, Escherichia coli, or infectious bronchitis, for example -- emerge during production, the only way to stop transmission to the next flock is through biosecurity and hygiene.

Where chemistry is concerned, a key aspect is disinfectant choice, but this is not the whole answer: cleaning must be done first. Water alone is not sufficient for this, as it will not remove biofilm, and so a detergent must be used.

When thinking about the pathogens to be inactivated, it is important to look at their strengths and weaknesses. All viruses, for example, are stable in neutral pH conditions, which includes in fecal matter, so cleaning must take place prior to disinfection. Some viruses, however, are more stable than others, and this will have implications for dilution.

Choosing the correct disinfectant is highly important, and must reflect which pathogens need to be inactivated.

Broad spectrum disinfectants are not the answer. Selection needs to be made based on which bacteria, fungi and viruses need to be inactivated and under which circumstances. Season and temperature, for example, can have a big impact. Also consider which surfaces need to be disinfected.

If continuous biosecurity is practiced, which is in the presence of birds, then a product that neither endangers birds nor workers – but that still kills pathogens – must be selected and, not lastly, stocks and logistics need to be considered.

All of the above must be considered if the right disinfection choice is to be made.

Biosecurity culture

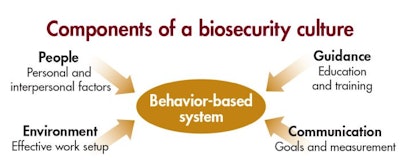

While the various elements and steps needed for good biosecurity may be established, they may not always be followed. How to ensure compliance and the implementation of a biosecurity culture was examined by Manon Racicot, veterinary epidemiologist, adjunct professor at the University of Montreal, who drew on various studies looking at compliance and how it can be influenced.

According to Manon Racicot, building a biosecurity culture is a value, not a priority. Priorities can change, while values should not.

To illustrate how poor compliance can be, she drew on studies carried out on 24 poultry farms in Quebec, in which eight farms were selected as a control to evaluate and describe the application of biosecurity measures when entering and exiting barns.

To achieve this, a camera was hidden in barn entrances for two 14-day periods, with filming taking place 24 hours a day, recording how well different areas were respected when changing boots, using the footbath, putting on coveralls, hand washing and using the log book

The results, from more than 800 visits made by 102 individuals, revealed an overall compliance of only 35 percent, although results varied widely depending on activity. Compliance with use of coveralls, for example, was found to be 71 percent, whereas for use of the log book it fell to 33 percent.

When examining the video surveillance of the 24 farms where cameras were used to see how employees used the areas immediately inside barn entrances, parameters were found to be significantly associated with compliance. Entrance designs were classified as being easy to follow, intermediate and difficult. Unsurprisingly, workers were 13 times more likely to respect areas when entrance designs made desired behavior easier.

Additionally, two types of area delimitation between clean and dirty areas were compared – a simple red line on the floor and a physical barrier, such as a bench. The physical barrier resulted in 5-9 times more chances of respecting the change in area classification, suggesting that employees tend to have issues with understanding and respecting delimited areas, which was reflected in the lowest compliance level of 15 percent.

The right people for the right job

Racicot's studies have also found that three personality types tend to be associated with good biosecurity compliance.

Those with personalities classed as “responsible,” tend to be conscientious toward work undertaken and do not compromise or bend the rules as far as promises and principles are concerned, while those classed as “action-orientated” react quickly to constraints in the environment, and become energetic when faced with tasks to accomplish or challenges to overcome. “Complexity” personalities value logical and rational approaches, and use complex strategies.

The findings could be used in the selection of poultry farm managers and supervisors, and they may then be able to positively influence co-workers.

It is also known that when people make a written commitment, their behavior is more likely to be consistent with what they have agreed to, and introducing such written commitments may have a positive influence on behavior.

Communication and feedback

While it is important to set biosecurity goals, it is also important to measure how well those goals are being met. Numerous approaches can be used, but none really reflect how compliant employees are or offer continuous monitoring.

A study in the hospital sector using radio frequency identification (RFID) technology has looked at how often health care professionals disinfect their hands prior to contact with patients, and a similar system will be trialed on two poultry farms over upcoming months in Quebec.

The trial will consist of inserting a chip into employees’ personal footwear, and into farm boots, while an antenna will be positioned on the barn entrance floor and connected to the hand sanitizer. For each visit, the antenna will detect if an employee has changed out of personal footwear and into farm boots, and will monitor sanitizing. If biosecurity breaches occur, they will be recorded and a real-time alarm will be sounded to modify behavior.

This system will allow evaluation of how effective education and training are, and could monitor compliance in real time.

Biosecurity compliance will remain a significant challenge as it is related to behavior, and building a behavior-based system will help in creating a biosecurity culture, Racicot said, continuing that it is worth remembering that building a culture is a value and not a priority. Priorities can change, but values should not.

View the webinar in full: