Targeted, bacterial killing viruses called bacteriophages are not new to poultry, but recent scientific and technical advances, as well as coming regulatory pressure, is spurring renewed interest in phage technology.

Bacteriophages

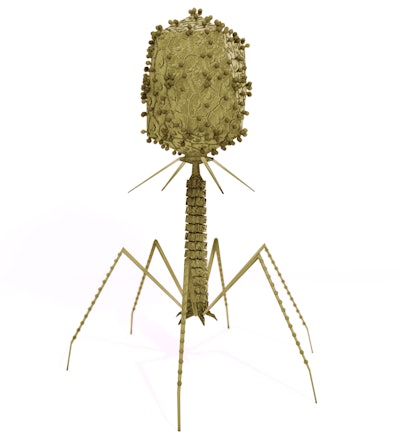

Bacteriophages, or phages, are viruses that infect only bacteria. Dr. Jason Gill, the associate director of the Center for Phage Technology (CPT) at Texas A&M University, said phages are the most abundant form of life on earth. Bacteria are everywhere along with bacteriophages.

The CPT is the first state funded phage research institute in the United States.

Gill, an associate professor at the university’s department of animal science, said phages are generally specific for their targets. Once they find the bacteria they seek, they infect the cell, take over the host and force it to make more phages that will destroy other bacteria.

In the poultry industry, phages are used to eliminate bacterial pathogens like Salmonella, Campylobacter and E. Coli.

The Iron Curtain

Despite these remarkable characteristics, phages are a somewhat unknown antimicrobial in the U.S.

Bacteriophages were discovered in 1917 and found to be an effective therapy for bacterial illnesses. However, Félix d'Hérelle, the man who named phages and championed phage therapy failed to expand and commercialize the technology in the Western world.

He took his research to the Soviet Union in 1934 where it was developed for medical uses. At nearly the same time, in 1928, penicillin was discovered and gained widespread use diminishing interest in phage technology outside the USSR.

Since much of the research was published in Russian during the Cold War, phage therapy was not well researched or understood outside the Soviet sphere. Gill said interest was revived in the West in the 1980s.

Phage research surrounding food safety and animal health took off in the early 2000’s, he said, largely due to concerns around antibiotic resistance in foodborne pathogens. Now, companies in the U.S., Europe and China are producing phage products.

Phages in poultry

Phages reproduce by killing bacteria, so they are cultured – or fermented – by exposure to a target species. Phages propagate until the bacteria is gone. Most commercial products, Gill said, are mixtures of multiple phages targeting different strains of a pathogenic species.

For the poultry industry phages are attractive because they are not antibiotics and can be used with probiotics since they do not target helpful bacteria, Gill said. Phages could have roles in both pre- and post-harvest pathogen control, but most products have been developed and approved for the post-harvest side, he said.

Conversely, the specific action of the phages means some site-specific strains of a pathogen could be missed and bacterial resistance can develop over time. For long term effectiveness, the phages need regular updating.

Bacteriophages are used in processing as an antimicrobial in the U.S. Will their use be expanded to preharvest, too?

(Anton Mislawsky I shutterstock.com)

Processing

Arm & Hammer markets phage products, and has for more than 10 years, for applications in beef and poultry, Dr. Jackson McReynolds, director of research and development at Arm & Hammer Animal and Food Production, said. Intralytix Inc. and Micreos also sell phage products in the U.S.

His company’s phages are fermented to a suitable concentration, clarified, filtered and tested for quality.

Phages are considered processing aids and are used as antimicrobials in the processing plant. Integrated protein producers and processors use phages as part of a multi-phase approach to reducing pathogens.

Arm & Hammer is currently focusing on Salmonella infantis, one of the most prevalent and troublesome strains, and is refining a cocktail more broadly addressing the pathogen.

As for use as a preharvest Salmonella intervention, McReynolds said regulations are different for preharvest than processing. He’s unsure if phage technology will impact the preharvest market “without some major work in regulation and approvals.” That isn’t likely to happen soon.

Preharvest

Elsewhere in the world, where regulatory approval is granted, phages are effectively used preharvest. Proteon Pharmaceuticals S.A. Chief Operating Officer Matthew Tebeau said his company’s phage products are administered through drinking water and feed like other additives.

The Polish company makes and sells bacteriophage products for use in livestock, poultry and aquaculture. It markets what it calls precision phage products developed with the assistance of genomics, molecular biology, bioinformatics and artificial intelligence. It launched its first product in 2019.

Currently, Proteon’s products are sold in Asia, South America and Africa. Tebeau said its aiming to get its products on the market in Europe and the U.S. soon. He said phage technology should be used beyond the plant.

In his view, bacteriophages may not get the attention they deserve because of their origins in Eastern Europe and the previous difficulty and high cost of commercial scale production. In the past decade, technology enabling the development of better, more targeted phages – genomic sequencing, for instance – became more available and affordable, allowing phage therapy to rapidly accelerate.

“The poultry industry in the U.S. and Europe will see a breakthrough when the products … are starting to be used in the live animal preharvest. Because that offers, in my view, the biggest benefit of using phages,” Tebeau said. “I think that's going to happen relatively soon, within the next one to two years.”

As part of a wider animal health strategy, phages used preharvest would be an important tool for producers allowing them to improve quality, reduce costs and reduce the risk of developing antimicrobial resistance.

The regulator’s role

In 2021, the United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Food Safety and Inspection Service’s director, Sandra Eskin, USDA deputy under secretary for food safety, announced the agency would be revising its policy toward Salmonella and Campylobacter. This policy decision would likely place a greater emphasis on using preharvest Salmonella interventions.

Further pressure was placed on the industry in August 2022, when Eskin announced Salmonella will be declared an adulterant on certain chicken products. That announcement left the door open to both expanding that declaration to other chicken parts and establishing a so-called zero tolerance policy for Salmonella.

For phages to advance in popularity in the U.S., Gill said the U.S. chicken industry will need proof phages provide good pathogen control at a reasonable cost. While academic research shows the phages work to reduce bacterial loads, he said, integrators need to see proof of consistent success in a variable commercial production environment.

Nevertheless, if regulatory forces apply pressure on Salmonella or Campylobacter, it could drum up additional interest in phages.

“If performance standards tighten or certain pathogens are declared as adulterants, that would certainly provide more incentive to be more aggressive with new interventions, both pre- and post-harvest.” Gill said.

USDA plans overhaul of food safety regulation www.WATTAgNet.com/articles/43902