Now is the time to examine how pig feed use is measured and managed on the farm, especially as the current higher grain prices are here to stay. The efficient use of all feed materials is the most important topic of modern pig farm management.

Feed terms defined

Looking internationally, the subject of managing pig feed efficiency at the farm level is often surrounded by confusion and uncertainty. Many pig producers are hesitant to undertake practical action because they are unsure what to measure or how to benchmark.

This confusion is not helped by the wide range of terms used in various countries for similar concepts. While some people talk about feed utilization or feed-to-gain, for example, others speak of gain-to-feed. No less confusingly, feed conversion ratio (FCR) may sometimes be referred to as feed conversion efficiency or FCE. There are further differences within these terms, such as when whole-herd or total FCR in closed herds is distinguished from the calculation made at dedicated finishing farms that concentrates on feed conversion ratios in the growing-finishing pigs.

Does any of this matter? It does, if it stops pig producers from setting targets that everyone on the team can understand and attempt to improve. The language can also affect attitudes and so shape actions.

Clearly stated feed goals

For example, the obvious difference between gain/feed and feed/gain as parameters is that improvement means in one an increase and in the other a decrease. Less obviously, however, they may lead to opposite directions in thinking, with the management team aiming to increase the output per unit of feed, or reduce the feed used per unit of gain.

“Be clear,” said speakers at an international conference on feed efficiency in swine organized by Iowa State University and Kansas State University in Omaha, Nebraska, USA, at the end of 2011. The guiding principle is to assess the output of the farm according to the quantity of feed used, as the first step in improving this critically important factor.

Feed efficiency describes the aim or the outcome, but it is not in itself a key performance indicator ready for measurement and management without more definition of the inputs and outputs involved. The simplest approach at every pig farm is to use the information already at hand so no additional recording is required.

This means applying the delivery or manufacturing record on feeds as the basis for weight of feed used and the sales register of animals for the output side of the ratio calculation.

Carcase weight produced

However, even the widely applied parameter of FCR needs to be more closely defined. For example, at farms that bring in weaned pigs and rear them for meat, the calculation of their feed conversion ratio is affected by the weights at which the animals arrive and leave. Adjusting the recorded FCR to take account of weight differences would allow a better comparison between pig farms.

An adjustment formula proposed in the United States suits market weights up to 115 kilograms. But the initial basis is still assumed to be an FCR measured in terms of live weight. This makes little sense when the money received by the farm for its meat pigs relates to the weight of the carcase, rather than of the live animal. They called for a change from using live FCR to one directly reflecting the ratio between feed used and carcase weight produced.

Most slaughter pigs are sold on a carcase basis and the carcase weights are given in the abattoir report, whereas live weights usually have to be calculated rather than measured. Moreover, management decisions for the pig farm can differ significantly, if based on live rather than carcase feed conversion ratios.

Using a carcase FCR calculation can be particularly useful where a practice such as feeding high-fiber diets creates a marked difference in weight gain measurements between results on a live basis and those expressed in carcass weight terms.

Consider the nutrients

Pig feed itself is a variable according to its composition. This too confuses attempts at comparing FCR, both from one pig farm to another and between periods in which the specification of the ration may have changed. Perhaps farm managers should not be thinking about the conversion of complete feeds, but instead consider how key nutrients are being converted.

Although this may seem like something more for researchers than for practical pig farmers, the conference observed how the cost of a ration is determined to a large extent by the energy it contains. Energy often accounts for 85 percent or more of a ration cost, compared with only 10 percent for protein. It makes a strong case that the main focus of our pig feed management should be on the conversion of energy into meat.

Today, the argument for considering nutrient efficiency in terms of the effect of the energy content becomes stronger still if lower-energy diets are advised as a means of controlling costs. It takes on even greater significance in the future, because the widespread expectation is that the feeds used after 2015 will be about 20 percent lower in energy because of an increased inclusion of materials containing more crude fiber. In fact, this likely change to feed specification for growing pigs is worth closer examination.

The first point to recognize is that supplying less energy should fit the changing requirements of the animals. While their need for energy for body maintenance will rise in line with increasing slaughter weights, at the same time they will require extra protein because they are leaner and more muscled.

Knowledgeable managers will respond by using weight-based feeding curves that add to the protein intake for each further increment of growth.

Feed efficiency in sow herds

The pig industry needs greater clarity in how to monitor feed efficiency in sow herds producing weaned pigs for sale. Currently, a herd may assess the amount of feed it has used—for sows, young pigs, breeding gilts and boars—against the number of pigs weaned, the number marketed or alternatively against the live or carcase weight produced.

While the general recommendation to sow managers is to deal with weight measurements both for input (feed) and for output (pigs) wherever possible, there also is the recognition that the most accessible records were likely to be of pig numbers produced. Such records would emphasize to the farmer that the feed efficiency of a herd producing piglets is directly related to sow productivity.

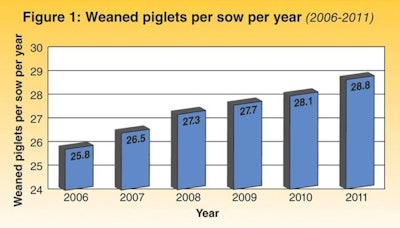

Dutch herds with TOPIGS sows are becoming more prolific every year, as shown in Figure 1. Out of 678 farms in the Netherlands recorded in 2011, no fewer than 164 succeeded in weaning 30 or more piglets per sow per year.

Obviously, this has a big influence on the quantity of sow feed used per piglet reared. Take as an example a herd in which the total feed for all breeding pigs amounts to an average of 1.15 tons per sow per year.

Figure 2 shows sow feed per piglet according to the number of piglets weaned per sow per year. The graph shows that the focus should be on feed efficiency (in the sense of pig output per ton of feed), rather than on feed conversion ratio (meaning weight of feed per pig or weight of pork produced). But we go further than that, by employing the term Total Feed Efficiency or TFE to include both piglet production and pig finishing activities.

An integrated or closed sow production system with grow-finish places has the advantage of not dealing in terms such as sow feed per piglet—it can include the feed for the breeding herd in its calculation of the amount used in producing a defined carcass weight of pigs marketed for meat.

At its simplest, this pig farm needs only to record the quantity of all breeding, rearing, growing and finishing feeds it receives over a certain period and compare the total with the carcase weights reported back from the abattoir. Finding how to achieve better performance is the whole point of the exercise. As better feed efficiency means more output per unit weight of feed, it will be achieved by increasing production, which means both winning extra pig performance and reducing the wastage due to losses.

In the breeding herd, both the rate at which sows are replaced and the weight at which piglets are born will have an impact on the system’s feed efficiency. At growing-finishing farms, managers should remember that the efficient use of feed is driven not only by the pigs’ daily weight gain and leanness or fatness, but also by the extent of the mortality rate among animals between arrival and marketing

Heat stress, feed intake

The environment around the animal undoubtedly exerts another influence. Pigs use their feed less efficiently if housed under conditions that are either too cold or too hot. Heat stress undermines the feed intake of the lactation sow.

Pig health is equally influential, with overwhelming evidence from all parts of the world that the animal’s response to a disease threat makes FCR figures worse by increasing its body temperature and mobilization of protein from the muscles besides raising the amount of feed energy it needs for physical maintenance.

However, the composition and form of the feed remain primary factors in determining how conversion rates will evolve. Generally, granulation or pelleting give a better FCR than with meal, which may be explained by reduced dustiness—although particle size is known to be important also for digestibility while poor pellet quality is typically no better than meal in terms of FCR results.

Composition involves not only the macro ingredients, but also the possible presence of additives or partitioning agents, such as ractopamine, which may result in a large improvement in growth rate and FCR. Consider, too, the better feed conversion ratios that can come from having well-adjusted feeders. Estimates of the waste of valuable feed, because of poor adjustment start at between 5 percent and 10 percent of total usage. The conveyor that carries feed from storage bin to feeder may also be at fault by crushing pellets causing more wastage.

Reduce feed losses

Taken together, these remarks offer a big clue to the actions any pig farm might consider to improve feed efficiency. They start with a campaign to reduce loss, in the realization that all forms of loss drain efficiency so feed invested is not harvested.

On feed costs alone, no unit can afford to lose pigs, whether in the farrowing house, the nursery or the finishing pen. But other losses also need to be taken into account, from the difference between eggs fertilized and piglets born to the proportion of sows that die or have to be culled as casualties.

Less obvious is the lost harvest when conception failure adds to the sow days that are open or non-productive.

The basic lesson is that livability and robustness are essential characteristics of the modern pig by reducing losses and therefore improving feed efficiency. The management of that animal then plays a critical role in emphasizing efficient feed use.