As energy prices rise, growers shouldn’t cut back on ventilation to save money this winter.

WATT PoultryUSA surveyed academics and poultry equipment manufacturers to share their best advice for caring for broilers and turkeys during the colder months of the year.

Cost differences

War in Eastern Europe, historic inflation in the United States and global economic uncertainty ensured the costs of electricity, propane and natural gas rose steadily in 2022. In the winter of 2022-2023, higher fuel costs will likely eat into profits for growers and integrators alike.

Most poultry farms use natural gas or liquid propane powered heaters to maintain a constant temperature in the house and warm chicks and pullets. Ventilation and air circulation equipment consumes much electricity, too. Prices of all heating fuels are expected to rise or stay elevated heading into the new year. There is also some concern about regional shortages as some occurred in the past.

The way costs are paid differs between farms and integrators. Some integrators pay the cost of heating fuel, or subsidize it, while others pay it themselves. Fuel buyers can lock in fuel pricing via a previous arrangement, too.

Randall Vickery, Aviagen’s regional technical manager for North America, said those who didn’t secure future pricing for this winter will struggle with high prices.

“Hopefully, the winter will not be severe for most of the broiler belt as long-range weather forecasts are promising,” Vickery said. “But for the northern growers in Canada and much of the turkey areas, it may not be as favorable.”

Balancing act

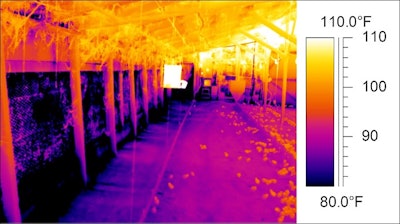

The manner of ventilating a flock varies greatly between hot summer months and temperate or cold winter months. In the summer, growers want to control heat. In the winter, the aim is to control air quality and moisture.

Trevor Houston, Space-Ray’s ag division manager, said the climate is arguably easier to control in the winter than the summer. In the hotter months, growers still need to heat young birds for brooding.

This creates a balancing act of needing to keep air moving but not so much that the excess air flow chills the birds. In winter, the grower heats the house to a desired temperature, reduces ventilation to a minimum and monitors oxygen and humidity levels.

Michael Czarick, an extension engineer at the University of Georgia’s Department of Poultry Science, said a new ventilation game begins in winter.

He said small differences in ventilation rates can either help or hurt the flock. Excessive ventilation can yield good air quality and bird performance but also create exceedingly high heating costs. Insufficient ventilation creates lower heating costs but worse air quality, which leads to wet litter, high ammonia, sick birds and overall reduced bird performance.

Moisture management

Therefore, Dr. Jon Moyle, an extension poultry specialist at the University of Maryland, said the objective of winter ventilation is to control moisture. Growers may not consider how much water flows into the house daily and underestimate the need to remove excess moisture.

House and ventilation design help to determine proper ventilation. Czarick said a house should bring fresh air from the side-wall inlets to prevent a draft, maximize heating of the air before it falls to the ground and reduce heating costs.

A response from the Chore-Time ventilation engineering group said using automated static pressure-controlled inlets ensures a proper mixture of incoming air and air speed to propel air to the center of the house. This helps keep temperatures uniform.

Georgia Poultry’s Ventilation Director Austin Baker said minimum ventilation fans must be sized right to create the correct air pressure and run on long cycle times. Stir fans will also help prevent air stratification when the main ventilation fans are off. Tabler also recommended using 18 to 24 inch fans to this end.

Litter quality and ammonia

Litter management is critical and more complex during the winter.

Along with creating welfare and health issues for the bird, wet litter elevates ammonia levels in the house. Ventilating to keep the in-house relative humidity under 70% and ammonia levels under 25 parts per million (ppm) will control litter moisture issues and prevent respiratory damage to the birds from ammonia exposure, Vickery said.

Like in summer, the Chore-Time engineering group said litter should be managed using windrowing or commercial litter treatments in between flocks. This reduces ammonia and its critical during the cooler months. When birds are in the house, the only way to knock down ammonia is to ventilate at high cost.

Czarick said windrowing is trickier in winter due to lower temperatures. The desired processes inside the windrow are not achieved if the proper internal temperature isn’t reached. Insufficient moisture removal can result.

Along with windrowing, Vickery said, growers should de-cake their litter to remove the wettest clumps. Moreover, he advocated for ventilating between flocks to remove additional moisture. Ventilating at a constant rate through the side wall or the attic inlets, rather than the tunnel inlets or open front doors, is best. Adding more warmth with heaters to further dry litter may be needed, especially in extreme cold.

Before placing the birds, Ben Carvell, application engineering manager at Valco Industries Inc., said litter amendments can be used to sequester ammonia. Additionally, he recommended preheating before placement of chicks.

Tabler said acidifying litter amendments are commonly used before placing chicks to drop the pH level for a short period of time.

Just as in summer, Carvell said to check all waterlines for proper height and pressure. Incorrect settings lead to more water getting into the litter via spills.

Cutting costs not corners

Everyone wants to cut costs, but cutting corners can lead to costly, hard to fix mistakes.

It’s not a good idea to cut back on ventilation to save money because of the potential moisture, litter quality and humidity issues. Czarick, Baker and the Chore-Time group agreed under ventilating, or under-heating the house, is particularly bad during the first 14 days of the flock when house temperature and bird performance have the greatest impact on the flock.

Carvell, Czarick, Vickery and Baker agreed its essential to make poultry houses and attic spaces as sealed up and airtight as possible. This is something that costs comparatively little and can yield large results for heating costs and bird performance.

Houston and Moyle recommended booking liquid propane gas in advance during the summer and storing it on site. Houston said investing in upgraded, larger storage to further this goal is worth it if growers can save money when prices rise in winter.

Moyle said growers can also join an electricity buying group to save money on electric rates in some areas.

Both said its worth spending money to upgrade to either more efficient machinery or more effective insulation. Moyle said newer, more efficient fans can save electricity. If a farm is 10 years or older, Houston said insulation in the attic may be insufficient. Adding more insulation is the cheapest and best way to save money on energy costs.

Houston and Carvell also recommended replacing older heaters and pilot light appliances with newer, direct spark versions or tube heaters to save gas. Radiant heaters, he said, can save as much as 20% on energy costs compared to air-type heaters.

Carvell also said deferred maintenance can add costs and create litter issues. Leaks, inlets hanging open, dusty shutters that won’t close, dirty fans and heaters not running efficiently all add hidden costs.