When a poultry company exceeds the maximum salmonella standard set by the authorities, the initial reaction is to place blame on the processing plant. Companies have spent much time and money attempting to reduce salmonella levels on finished carcasses by making changes in the plant, not always with success because the level of salmonella contamination on finished product depends on each stage of the production chain.

Breeders

Salmonella may be transferred on the surface of the eggshell by faecal contamination during laying, or it may be encased within the egg. These bacteria have been found in the reproductive tract of roosters and in hens' sperm storage tubules, indicating the likelihood of infection during insemination.

Increasingly in Europe, breeder flocks are tested regularly for salmonella. If the breeder flock is positive, it is slaughtered and the eggs may not be used. This has dramatically reduced salmonella populations in the broiler chickens.

Vaccination

Some companies that have instituted a vaccination programme have shown lower salmonella counts in their breeders. Others have not found the programmes to be satisfactory because not all vaccines are effective against all serotypes.

Competitive exclusion

Another approach in European countries is the use of competitive exclusion products in the breeder feed. The theory is that by feeding the birds ‘good' bacteria, these will colonise the intestines of the chickens. So when pathogenic bacteria such as salmonella are ingested, they find no place to attach to the gut lining and/or they are killed by the bacteriocins (bacterial antibiotics) produced by the ‘good' bacteria. The cultures used in competitive exclusion products are not always fully identified, which prevents authorisation in some countries.

Hatchery

Intervention strategies should be implemented during the hatching phase as salmonella have been found almost everywhere, including in breeder nest boxes, egg-storage rooms, hatchery trucks and in the hatchery itself. Bacteria spread to fertilised hatching eggs on the shell. In rare cases, they may penetrate the shell and reside just beneath its inner surface.

Cleaning and sanitisation

Research has demonstrated that salmonella contamination of raw poultry products can start by cross-contamination from infected eggs or surfaces during the hatching process. Work published in 1990 showed that within the hatchery, 71% of eggshell fragments, 80% of chick conveyor belts swabs and 74% of pad samples placed under newly hatched chicks were salmonella-positive.

Fertile eggs contaminated with high levels of Salmonella typhimurium will hatch normally, and there are no adverse effects on chick health. However, the bacteria are spread rapidly throughout the hatching cabinet by the circulation fans. When eggs were inoculated with a marker strain of salmonella during hatching, more than 80% of the chicks in the trays above and below the inoculated eggs were contaminated. Bacteria on the exterior of eggs or in eggshell membranes can be transmitted to chicks during pipping.

Salmonella persist in hatchery environments for a long period: when dander (chick fluff) contaminated with salmonella was held for four years at room temperature, up to one million cells per gramme were recovered from the sample.

Researchers have demonstrated a link between cross-contamination in the hatchery and salmonella-positive carcasses during processing, based on the same serotypes being found at both locations. High levels of cleanliness and hygiene in the hatchery are thus essential to prevent this cross-contamination.

Reductions of 20-50% in salmonella in broiler chickens can be achieved spraying chicks with a live vaccine in the hatchery. As with breeders, some European growers have found that undefined competitive exclusion cultures can also be successful.

Examples of successful sanitation procedures in the hatchery include a disinfectant fogging system or electrostatic spraying system in the hatchery plenum, setters and hatchers, linked to a timer system. During setting and hatching, spraying disinfectant every 30 minutes will help prevent cross-contamination. Setters and hatchers must be regularly and thoroughly cleaned and disinfected. All these actions should be properly documented in standard operating procedures.

Monitoring efficacy

To assess the efficacy of these measures, eggshell fragments, chick paper pads and chick dander from the bottom of the hatching cabinet should be monitored regularly for salmonella.

Broiler growing

Among other attributes, today's broilers have been bred for their high feed intake, which is a significant advantage in terms of efficient growth. One drawback is that during feed withdrawal during the last 3-7 hours before catching, the birds will peck at the litter in their search for feed. This increases the risk of them becoming infected with salmonella and other pathogens, particularly in the crop. Infection can easily spread further if the crop ruptures during the crop removal process.

Studies using dyes have clearly demonstrated that commercial crop removal can result in a large amount of contamination of the inside and outside of the carcasses.

Water treatment

Some poultry companies have successfully controlled salmonella in the crop by acidifying the drinking water during feed withdrawal. Acetic, citric or lactic acids and Poultry Water Treatment (PWT) have all been used to acidify the crop sufficient to kill salmonella. Lactic acid (0.44% concentration) reduced the proportion of salmonella-contaminated crops by 80% in one trial. Pathogen prevalance in pre-chill carcasses was reduced by 52%.

It is best to gradually expose the birds to progressively higher levels of acid in the water during the week before harvesting to prevent a drop in water intake. A periodic check of crop pH at the plant will ensure that the acid level is effective.

Feed withdrawal

Prior to evisceration, carcasses should be evaluated to determine if the birds have undergone proper feed withdrawal. A convex abdominal cavity may indicate the presence of too much faeceal material.

After evisceration, the intestines hanging from the birds should be flat, not full of faeces or bloated. Bloating occurs when the birds have been off feed for too long. Combined with the lower tensile strength of the intestines of starved birds, any salmonella (or other gut contamination) is likely to be distributed further, contaminating more carcasses and equipment.

Insufficient feed withdrawal time is perhaps the most important factor in meeting the zero tolerance standard for contamination on carcasses entering the chiller. If this period is too short (less than 8 hours), the intestines will be full of digesta. If nicked during evisceration or venting, contamination can spread widely.

Transport crate sanitisation

Conventional crate (cage)-dump systems used in the poultry industry are difficult to clean but they must be thoroughly washed to remove even dry excreta, and sanitised. Ineffective washing may simply allow any salmonella to proliferate.

Reducing salmonella contamination on fully processed, ready-to-cook carcasses requires a comprehensive approach that includes the entire integrated broiler operation. Effort is required at each stage of the production chain from breeder to processing plant to ensure that poultrymeat is safe for consumers.

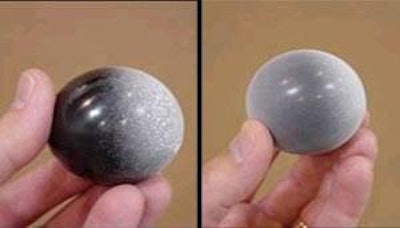

Chart 1: Electrostatic spraying of eggs with electolysed oxidative (EO)water reduces salmonella colonisation in chicks