Known locally as blue-ear disease, the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome PRRS has been causing extensive losses in the pig sectors of China and Vietnam. Subsequently there have been concerns throughout Asia about the magnitude of the outbreak and its effect on pig industries and markets in the region.

A constant worry is the possibility of disease being transmitted between countries by cross-border trade. In a note to an electronic discussion group on meat trade issues, Nancy Morgan, livestock policy officer at the Asian regional office of United Nations Food/Agriculture Organisation (FAO), has described examining the relative price movements of live pigs within the region in the wake of PRRS both to see the market impact and as a potentially useful early-warning indicator of where animals will move.

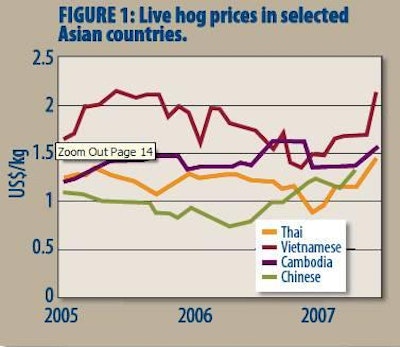

The accompanying graphs depict the pattern of prices for live pigs in the Asian region and in the individual countries of Vietnam, Cambodia and Thailand. With them is a chart comparing feed price changes (based on US maize prices) with live-pig prices in China. Observers comment that the Chinese market for pork this year has been affected partly by the lower pig supply due to more expensive feeds, but more obviously by the extent of pigs lost to disease.

Price differences between neighbours Vietnam and Cambodia customarily dictate the trade in pigs between them. The story in 2006 was one of relatively high Cambodian prices that had the effect of drawing in large shipments of pigs from Vietnam, where the local price had dipped suddenly. The analysis by Nancy Morgan and colleagues in Asia confirms that 2007 price levels in Cambodia have been extremely high because of a shortage of pigs after market shocks last year resulted in a reduction in farrowings. By early September the selling price of live pigs had risen to a high of 7500 riel per kilogram (about US$1.80/kg) from a low of 3800 riel (90 US cents) in early August, on figures from the Cambodian Pig Raisers Association.

But, from a mid-year perspective, Vietnam's prices could be seen to be rising even more steeply so that there was little incentive to send Vietnamese pigs across the border. Trade prospects have decreased even more since then, with the decision by the Cambodian government to impose a ban on the importation of pigs and pork from neighbouring countries. The ban was called a response to livestock disease abroad as well as a way to protect and develop the local pig industry.

The fear regionally now is that high prices in Cambodia will trigger illegal imports, potentially leading to the further spread of PRRS and other diseases.

Tests to profile Vietnamese pathogens

Deaths of pigs in parts of Vietnam this year have been blamed on PRRS-related disease, but a number of swine pathogens may be interacting to cause the unusual signs being observed. That was the view of an international team of veterinary experts sent to Vietnam after this year's outbreaks in the country.

Identifying the exact nature of the health challenge has been an ongoing process. A statement by FAO referred only to PRRS being one of the possible causes of the disease being reported in Vietnam. Preliminary tests in the USA tested negative for African swine fever, classical swine fever/hog cholera and foot-and-mouth disease. FAO has also reported that samples from affected Vietnamese pigs had been sent to an international laboratory for genetic sequencing to determine the type of the virus and identify an appropriate vaccine.

The team of foreign and Vietnamese experts asked to investigate recent deaths among pigs, in response to a request from the authorities in Vietnam, was commissioned by the animal health crisis management centre operated jointly by FAO and world animal health organisation OIE. Following an investigation in central and northern Vietnam, they announced finding that about 10-15% of affected pigs had died in the recent outbreaks. In their view, this mortality rate was not considered unusually high for livestock in south-east Asia.

They said many of the diseases, including PRRS, could be brought under control by improving overall disease management. To control the problem, FAO recommended the implementation of good pig production practices on small farms. Team leader Dr Carolyn Benigno pointed out that sick pigs could be cured from secondary infections by an appropriate use of approved antibiotic injections and this would greatly reduce the losses. It was also noted that PRRS is known to reduce immunity in pigs and lead to secondary infections of bacterial diseases such as Streptococcus suis, Haemophilus parasuis and Salmonella, as well as being associated with other viruses.