In seminars, especially those given to an audience of animal producers, I am often required to explain why the feed industry is using nutrient levels beyond those recommended by public institutions. For example, we use up to 10 times higher levels for some vitamins, and this might be considered a waste of nutrients and money. But, there are some good reasons that quite often require the use of generous safety margins. In many cases, however, it is insecurity that causes many feed formulators to burden animal diets with extra nutrients; the same can be said about additives that are being only "added on" and never "taken out."

So, let’s discuss why we use safety margins. By this, we might be able to appreciate when they are required and when they are not so we can avoid wastage and expense.

Experimental designs

Most nutrient requirement studies have been conducted under ideal experimental conditions that are generally deemed more favorable than current commercial conditions. In such experiments, diets are carefully prepared from ingredients of known chemical composition, and they are fed shortly after mixing to avoid nutrient losses. Thus, most commercial nutritionists add a margin of safety over published nutrient requirement estimates to account for variables that are hard or impossible to control or even predict during feed preparation and use. The following is a non-exclusive list of cases that call for margins of safety:

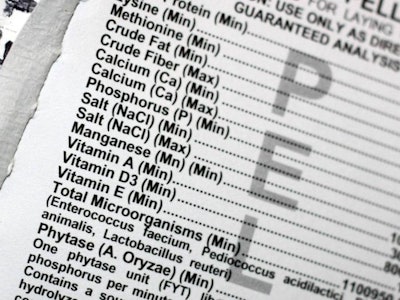

Label guarantees. By definition, in least-cost formulations the probability for any nutrient to be below target is always 50 percent. The same is true for being above target, but any client is more prone to complain if the feed is wanting rather than in excess. Thus, most commercial feeds are always slightly over-fortified to meet declared concentrations (the label or tag on feed bags) as required by law.

Nutrient variability. Certain ingredients can be highly variable in terms of nutrient composition. Agro-industrial products of unknown quality and origin can be highly problematic if they are not assayed frequently, especially if they make up a substantial part of a diet. Most, but not all, large feed manufacturers test such variable products on a frequent basis, but still they cannot test every batch for all possible nutrients. So, when by-products are heavily used, safety margins usually go up.

Formulation basis. Diets formulated on total rather than digestible nutrient basis are often over-fortified to account for unknown variability in nutrient digestibility, especially in low-quality and novel ingredients. In contrast, using more modern methods of feed formulation may result in reduced nutrient wastage, albeit at a higher end cost if more digestible ingredients are required for special young animal feeds; this is always a wise investment.

Nutrient losses. Several nutrients (for example, amino acids and vitamins) are susceptible to destruction during thermal processing (pelleting, expanding, flaking) and also during prolonged storage where significant losses of bioavailability may occur. Amino acids, and especially feed-grade lysine, is very prone to the Maillard reaction that renders them useless. Vitamins can be impacted by temperature and humidity, and also by interaction with trace minerals. So, when one uses a common vitamin and trace mineral premix instead of two separate products, it is more likely to use more generous margins.

The “average” animal. Published nutrient requirements usually refer to the “average” animal, which in reality does not exist. This definition of convenience leaves half of animals in any group undernourished while the other half is always overfed. Of course, animals can partially compensate by adjusting their feed intake, but there are limits to that, as well. This is why individually-housed animals always eat and grow more than group-housed animals. Feeding the average animal is something we will continue to work towards, and over-supplementation appears to be the only way to push group performance up, albeit at an expense that brings an ever-decreasing profit as we approach genetic potential.

In brief

Minimizing unknown factors and monitoring quality in ingredients and finished diets obviously reduces the need for excessive safety margins. If animal performance (weight gain, egg production and feed intake) is known from long-term records, then a feeding program with minimal safety margins that closely meets requirements can be easily designed to reduce feeding cost. To this end, modeling programs can be of assistance.