Although researchers and scientists have the facts to back up their arguments, how they communicate with the general public is not effective, according to Dr. Alison van Eenennaam, of the department of animal science at University of California-Davis.

Scientific presentations are dull and boring, van Eenennaam said.

“But the general public in science communication wants almost the exact opposite. They want a narrative story that’s being told. They’re responding quite often with their gut rather than their head, they love humor, they love sex appeal, they want sincerity. They want to know you’re doing what you’re doing for the right reasons. They want to trust you. They’re listening with their hearts and guts and gonads. The preferred voice is a human voice.

“So, it’s not surprising, when you get a monotone scientist up there giving an objective discussion of information to people, it’s not a very compelling story,” she said.

A much more effective approach to scientific communication is to use trust, emotion and social identity.

And, according to van Eenennaam, plant and animal breeders, like herself, have perhaps the most compelling sustainability story of all time.

“The application of conventional breeding in our agricultural production systems has come along with some tremendous environmental benefits that perhaps is the unsung hero of sustainability,” she said.

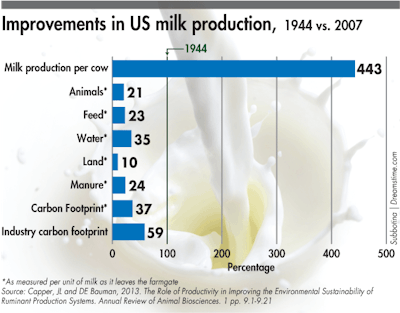

For example, about half of the 369 percent increase in dairy milk production efficiency in the past 100 years is attributable to genetic improvement enabled by artificial insemination which, like genetic engineering, once was a controversial technology, van Eenennaam said.

Appeal to shared values

van Eenennaam said there are three available means of persuasion: appealing to logic, ethics and, most importantly, emotions and values.

“A more effective approach to science communication (is to point out) where we have shared values,” she said.

A conspiracy theory that is popular online is that “they (big agriculture producers) are the enemy and we (consumers) need to work together to stop them.”

“These narratives that are based on fear are really hard to fight using facts. If you bring facts to that, you’re not going to be very successful,” van Eenennaam said. Instead, appealing to the shared values of the audience and the agricultural community can be more effective.

“I’d argue that there’s a lot of undecided people as it relates to technologies and agriculture because there’s not a lot of understanding of agriculture and that finding what we do, in line with the values that are important to them, particularly as it relates to the environment, is a way to shift the conversation away from facts to the shared values,” she said.

Sustainability is a shared value among both sides, but van Eenennaam said there is a lot of confusion around that topic.

“We’re aware that there are conflicts between the three components of sustainability (environmental, social and economic) and sometimes if you put too much emphasis on one – for example, animal welfare and cage-free chickens – you’re going to have very serious effects on the other components of sustainability,” she said.

There is confusion in the marketplace because there are so many labels that suggest one company or product has the only truly sustainable system.

“Many of the decisions that consumers are making in the marketplace don’t align with that shared value, and I think it’s because they’ve been misled or, in fact, lied to, by groups that are trying to gain market share by suggesting that their particular production system is more sustainable,” she said. “It’s really working against the enterprise of agricultural research, which is trying to improve the efficiency of agricultural production.”

And that has led to consumer demand for practices that are not the most sustainable.

“Where the market went is not in alignment with the sustainability goals as it relates to the environment,” she said. “I’m concerned that the marketing is going in exactly the opposite direction of sustainability.”

Fear driving market changes

van Eenennaam said she is concerned that fear, not science, will cause more sustainable products and technologies to be driven from the market.

“I care because of the documented benefits of this technology and the fact of what happened to rBST (recombinant bovine somatotropin) is that technology is now gone. I’m concerned that we’re going to lose more technology as people are able to create fear around it and basically have an increased market share by scaring people away from perfectly safe technology.”

She said absence labeling started with rBST-free milk, and that fearmongering led to removal of the product from the marketplace, even though it was found to be safe and reduced greenhouse gases in milk production.

As another example, genetic engineering has reduced global pesticide spraying by 618.7 million kg (8.1 percent) and, as a result, decreased the environmental impact associated with herbicide and insecticide use on these crops by 18.6 percent. It has also allowed for use of less toxic herbicides and insecticides.

The 2007 U.S. milk production, resource use and emissions expressed as a percentage of the 1944 dairy production system.

However, van Eenennaam said, the agreement gap on genetically modified food between U.S. adults and scientists is 51 percent; 88 percent of scientists think it’s safe while only 37 percent of the public thinks it’s safe.

This is why she said it is important for the scientific community to stand up for what it knows is safe and sustainable.

“It’s time to be a little bit more vocal as a scientific community devoted to try to introduce safe technology to agriculture. When we see technology getting demonized, call it out for what it is.”

And, she said, that demonization is harmful.

“There is a real need for me to defend the objective truth, especially around food and agriculture, because these alternative facts and these absence labels are doing real damage,” she said. “In one fell swoop, these decisions that are made as it relates to some of these absence claims can decrease efficiency by 10 percent – or , in the case of cage-free chickens, by 50 percent – as a result of these incorrect claims.”

van Eenennaam spoke in March 2018 at the American Feed Industry Association’s Purchasing and Ingredient Suppliers Conference in Fort Worth, Texas.