In the early 1950s a water tank on the roof of Morrison Hall at Cornell University served as the research station for growing microalgae as a feed supplement. Professor Wilson G. Pond was researching the nutritional benefits of feeding microalgae to livestock.

Now, Pond’s mentee, Cornell University professor of molecular nutrition, Xingen Lei, is among scientists at 10 different institutions worldwide studying the nutritional benefits of microalgae as a biofuel byproduct — the defatted, dried form of microalgae.

In the animal feed industry, if microalgae replaced 20 to 50 percent of the soybean meal fed to swine, broilers and layers each year it would save 4.4 to 11 million tons of soybean meal that could be used for human consumption.

Microalgae byproduct scores high in protein

“Microalgae have become a revitalized interest because of the multiple crises we’re facing today, like feeding the growing world population,” says Lei.

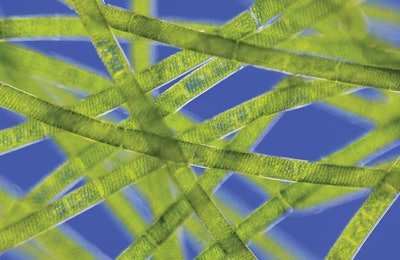

By 2020, the global feed market will need to produce more than 220 million tons of protein. And microalgae contains a lot of protein — between 20 to 70 percent. Compare this to 10 percent protein in corn and 40 percent protein in soybeans. Microalgae are also a good source for lipids and carbohydrates.

Some species of microalgae are a good source of protein, lipids and carbohydrates in animal feed. | BioMed Central Ltd

In addition, this protein source is highly digestible by non-ruminant animals.

“Microalgae are single cell proteins, so they should be less digestible than soybeans or conventional proteins,” says Lei. “But we found in our research that the digestion is the same if not better.”

Lei’s research, titled “Dual potential of microalgae as a sustainable biofuel feedstock and animal feed,” shows that pigs that were fed a diet supplemented with 10 to 15 percent microalgae exhibited the same body lean yield as pigs that were fed a conventional diet of corn and soybean meal. There were no signs of overt toxicity at these levels.

Likewise, supplementing 10 percent of soybean meal with microalgae for broilers and layers had no adverse effects. Broilers fed 10 percent microalgae on an as-fed basis had similar weight gains as those fed a conventional diet. And layers showed similar production rate and egg weight. The biggest difference was that the egg yolks had 24 percent less cholesterol when the layers were fed a diet supplemented with 10 percent microalgae.

Benefits of feeding microalgae versus the cost of production

While microalgae aren’t predicted to replace staple grains like corn, wheat and soybeans it is seen as a viable way to help feed the increasing population. The U.S. exports more than one million pigs each year, and each market pig consumes approximately 660 pounds of feed during its lifespan. Feeding microalgae as a protein supplement could help to offset the high feed cost.

“We just need to figure out how to integrate it into our current system and make a stable supply,” says Lei. The agriculture industry would need to partner with the biofuel industry to make this a viable option and take advantage of the nutritional benefits of microalgae as a byproduct.

Macroalgae provides alternative benefits as a feed additive

Macroalgae or seaweed — a cousin to microalgae— is also making an impact on the feed industry as an additive to help boost immunity.

“Seaweed is very unique because it has sulfates attached to the polysaccharides,” says Olmix animal health product specialist Paul Olsen, DVM. “This is something we only see in marine plants.”

A 2012 field trial in Spain using a macroalgae toxin binder reduced the amount of milk wasted due to mastitis or antibiotic use. The compounds in macroalgae help to bind toxins that would otherwise be absorbed by the animal. | Laura Fernandez

These specific polysaccharides found in macroalgae are used in toxin binders for their ability to mitigate the negative effects of toxins in feeds. While the unique biological activity found in other sulfated polysaccharides improves immunity and helps animals metabolize fats more efficiently.

“We’re taking specific molecular compounds from seaweed to help animals be healthier,” says Olsen. These compounds have been shown to boost immunity and to help animals when administered to the feed around times of stress, i.e. moving, and vaccinating.

“We might give this to baby chicks when they’re brought into the barn to help them deal with stress, so they have a much better response,” says Olsen noting that macroalgae can be fed as additives during times of stress and does not need to be fed daily to animals.

Feeding macroalgae as additives can’t replace antibiotics; however, it is an alternative that producers can use to keep their animals healthy.

“The antibiotic-free movement is really snowballing right now,” says Olsen. “What the compounds in macroalgae do is to help make it possible to raise these animals in close population without adding low levels of antibiotics to the feed.”

Growing population and consumer demand to shape the future for algae

While the research in micro- and macro-algae goes back for years, it is only in recent years that using this research has become a necessity.

“In the long term, if we can use microalgae to produce biofuel and food simultaneously, we will cut down the carbon footprint of food production and free the land usage to meet the increasing demands for fuel and food,” says Lei.

And with the increasing demand for foods is the increasing consumer demand for antibiotic-free protein. “Most of this antibiotic-free movement has been geared towards poultry and swine. And in the next few years it is going to be geared towards dairy and beef,” says Olsen. “Government regulations are going to play into this, and livestock producers need a viable alternative.”

And that alternative may very well be algae.